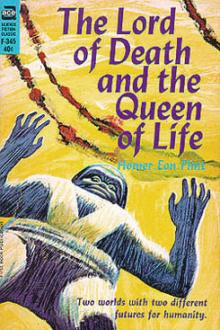

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Homer Eon Flint

As the thing went on the four men came closer and watched the operation of the machine. The ribbon unrolled slowly; it was plain that, if the one topic occupied the whole reel, then it must have the length of an ordinary chapter. And as the voice continued, certain dramatic qualities came out and governed the words, utterly incomprehensible though they were. There was a real thrill to it.

After a while they stopped the thing. “No use listening to this now,” as the doctor said. “We’ve got to learn a good deal more about these people before we can guess what it all means.”

And yet, although all were very hungry, on Jackson’s suggestion they tried out one of the “records” that was brought from that baffling anteroom. Smith was very much interested in that unopened door, and Van Emmon was in the midst of it when Jackson started the motor.

The geologist’s words stuck in his throat. The disk was actually shaking with the vibrations of a most terrific voice. Prodigiously loud and powerful, its booming, resonant bass smote the ears like the roll of thunder. It was irresistible in its force, compelling in its assurance, masterful and strong to an overpowering degree. Involuntarily the men from the earth stepped back.

On it roared and rumbled, speaking the same language as that of the other record; but whereas the first speaker merely USED the words, the last speaker demolished them. One felt that he had extracted every ounce of power in the language, leaving it weak and flabby, unfit for further use. He threw out his sentences as though done with them; not boldly, not defiantly, least of all, tentatively, he spoke with a certainty and force that came from a knowledge that he could compel, rather than induce his hearers to believe.

It took a little nerve to shut him off; Van Emmon was the one who did it. Somehow they all felt immensely relieved when the gigantic voice was silenced; and at once began discussing the thing with great earnestness. Jackson was for assuming that the first record was worn and old, the last one, fresh and new; but after examining both tapes under a glass, and seeing how equally clear cut and sharp the impressions all were, they agreed that the extraordinary voice they had heard was practically true to life.

They tried out the rest of the records in that batch, finding that they were all by the same speaker. Nowhere among the ribbons brought from the library was another of his making, although a great number of different voices was included; neither was there another talker with a fifth the volume, the resonance, the absolute power of conviction that this unknown colossus possessed.

Of course this is no place to describe the laborious process of interpreting these documents, records of a past which was gone before earth’s mankind had even begun. The work involved the study of countless photos, covering everything from inscriptions to parts of machinery, and other details which furnished clue after clue to that superancient language. It was not deciphered, in fact, until several years after the explorers had submitted their finds to the world’s foremost lexicographers, antiquarians and paleontologists. Even today some of it is disputed.

But right here is, most emphatically, the place to insert the tale told by that unparalleled voice. And incredible though it may seem, as judged by the standards of the peoples of this earth, the account is fairly proved by the facts uncovered by the expedition. It would be but begging the question to doubt the genuineness of the thing; and if, understanding the language, one were to hear the original as it fell, word for word from the iron mouth of Strokor [Footnote: Translator’s note—In the Mercurian language, stroke means iron, or heart.] the Great-hearing, one would believe; none could doubt, nor would.

And so it does not do him justice to set it down in ordinary print. One must imagine the story being related by Stentor himself; must conceive of each word falling like the blow of a mammoth sledge. The tale was not told—it was BELLOWED; and this is how it ran:

I am Strokor, son of Strok, the armorer. I am Strokor, a maker of tools of war; Strokor, the mightiest man in the world; Strokor, whose wisdom outwitted the hordes of Klow; Strokor, who has never feared, and never failed. Let him who dares, dispute it. I—I am Strokor!

In my youth I was, as now, the marvel of all who saw. I was ever robust and daring, and naught but much older, bigger lads could outdo me. I balked at nothing, be it a game or a battle; it was, and forever shall be, my chief delight to best all others.

‘Twas from my mother that I gained my huge frame and sound heart. In truth, I am very like her, now that I think upon it. She, too, was indomitable in battle, and famed for her liking for strife. No doubt ‘twas her stalwart figure that caught my father’s fancy.

Aye, my mother was a very likely woman, but she boasted no brains. “I need no cunning,” I remember she said; and he who was so unlucky in battle as to fall into her hands could vouch for the truth of it—as long as he lived, which would not be long. She was a grand woman, slow to anger and a match for many a good pair of men. Often, as a lad, have I carried the marks of her punishment for the most of a year.

And thus it seems that I owe my head to my father. He was a marvelously clever man, dexterous with hand and brain alike. Moreover, he was no weakling; perchance I should credit him with some of my agility, for he was famed as a gymnast, though not a powerful one. ‘Twas he who taught me how to disable my enemy with a mere clutch of the neck at a certain spot.

But Strok, the armorer, was feared most because of his brain, and his knack of using his mind to the undoing of others. And he taught me all that he knew; taught me all that he had learned in a lifetime of fighting for the emperor, of mending the complicated machines in the armory, of contact with the chemists who wrought the secret alloy, and the chiefs who led the army.

Some of this he taught me when I was not yet a man. Why he should have done so, I know not, save that he seemed to value my affection, and liked not my mother’s demands that I heed her call, not his. At all events, I oft found his shop a place of refuge from her wrath; and I early came to value his teachings.

When I became a man he abruptly ended the practice. I think he saw that I was become as dexterous as he with the tools of the craft, and he feared lest I know more than he. Well he might; the day I realized this I laughed long and loud. And from that time forth he taught me, not because he chose to, but because I bent a chisel in my bare hands, before his eyes, and told him his place.

Many times he strove to trick me, and more than once he all but caught me in some trap. He was a crafty man, and relied not upon brawn, but upon wits. Yet I was ever on the watch, and I but learned the more from him.

“Ye are very kind,” I mocked him one morning. When I had taken my seat a huge weight had dropped from above and crushed my stool to splinters, much as it would have crushed my skull had I not leaped instantly aside. “Ye are kinder than most fathers, who teach their sons nothing at all.”

He foamed at his mouth in his rage and discomfiture. “Insolent whelp!” he snarled. “Thou art quick as a cat on thy feet!”

But I was not to be appeased by words. I smote him on the chest with my bare hand, so that he fell on the far side of the room. “Let that be a warning,” I told him, when he had recovered, some time later. “If ye have any more tricks, try them for, not on, me.” Which I claim to be a neat twist of words.

It was not long after that when I saw a change in my father. He no longer tried to snare me; instead, he began, of his own free will, to train my mind to other than warlike things. At first, I was suspicious enough. I looked for new traps, and watched all the closer. I told him that his next try would surely be his last, and I meant it.

But the time came when I saw that my father was reconciled to his master. I saw that he genuinely admitted my prowess; and where he formerly envied me, he now took great pride in all I accomplished, and claimed that it was but his own brains acting through my body.

I let him indulge in the conceit. I grudged it not to him, so long as he taught me. In truth, he was so eager to add to my store of facts, so intent upon filling my head with what filled his, that at times I was fairly compelled to stop him, lest I tire.

My mother opposed all this. “The lad needs none of thy wiles,” she gibed. “He is no stripling; he is a man’s man, and a fit son of his mother.”

“Aye,” quoth my father slyly. “He has thy muscle and thy courage. Thank Jon, he hath not thy empty head!”

Whereat she flew at him. Had she caught him, she would have destroyed him, such was her rage; and afterwards she would have mourned her folly and mayhap have injured herself; for she loved him greatly. But he stepped aside just in the nick of time, and she crashed into the wall behind him with such force that she was senseless for a time. I remember it well.

And yet, to give credit where credit is due, I must admit that I owe a great deal to that gray-beard, Maka, the star-gazer. But for him, perchance, the name of Strokor would mean but little, for ‘twas he who gave me ambition.

Truly it was an uncommon affair, my first meeting with him. Now that I shake my memory for it, it seems that something else of like consequence came to pass on the same occasion. Curious; but I have not thought on it for many days.

Yes, it is true; I met Maka on the very morn that I first laid eyes on the girl Ave.

I was returning from the northland at the time. A rumor had come down to Vlama that one of the people in the snow country had seen a lone specimen of the mulikka. Now these were but a myth. No man living remembers when the carvings on the House of Learning were made, and all the wise men say that it hath been ages since any being other than man roamed the world. Yet, I was young. I determined to search for the thing anyhow; and ‘twas only after wasting many days in the snow that I cursed my luck, and turned back.

I was afoot, for the going was too rough for my chariot. I had not yet quit the wilderness before, from a height, I spied a group of people ascending

Comments (0)