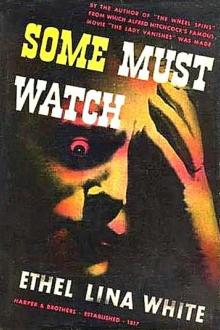

Some Must Watch, Ethel Lina White [crime books to read txt] 📗

- Author: Ethel Lina White

- Performer: -

Book online «Some Must Watch, Ethel Lina White [crime books to read txt] 📗». Author Ethel Lina White

furniture was merely incidental to the books and papers—supplemented in

the case of the Professor, by files and shelves of volumes of

reference. There was no trace of the comfort usually characteristic of a

man’s den—no shabby Varsity chair, no old slippers, or tobacco-jar.

The Professor sat at his American roll-top desk, his finger-tips pressed

against his temples. When he looked up, his face appeared blanched and

strained.

“Headache?” asked the doctor.

“So—so,” was the reply.

Helen bit her tongue to keep back her impulsive offer of aspirin, as she

felt that professional advice should take preference.

“Take anything?” asked Dr. Parry casually.

“Yes.”

“Good… The new nurse wants Miss Capel to take duty, tonight. I

forbid it. Lady Warren’s heart is in a bad way, and she is in too

critical a condition to be left in the charge of an untrained girl. Will

you see that this order stands?”

As he listened, the Professor kept his fingers pressed over his

eyeballs.

“Certainly,” he agreed.

When they were outside, Helen turned to the doctor, her eyes limpid with

gratitude.

“You don’t know what this means to me,” she said.

“You—”

She broke off at the shrilling of the telephone-bell. As the instrument

was in the hall, she rushed to answer it.

“Hold on, please,” she said, beckoning to Dr. Parry. “The call’s for

you. Someone’s ringing up from the Bull. He asked if you were here.”

With her evergreen interest in the affairs of others, she tried to

reconstruct the inaudible part of the conversation from listening to Dr.

Parry’s end of the line.

“That you, Williams?” he asked. “What’s the trouble?”

His casual tone dulled to incredulity, as he heard, and then sharpened

to a note of horror.

“What?… Impossible… What a horrible thing. I’ll come at

once.”

When he hung up, his expression testified to the fact that the

telephone-message had proved a shock. While Helen waited for him to

speak, Miss Warren came into the hall.

“Was that the telephone-bell?” she asked vaguely.

“Yes,” replied Dr. Parry. “Do you remember a girl Ceridwen Owen—who used

to work here? Well, she’s dead. Her body has just been discovered inside

a garden.”

AN ARTICLE OF FAITH

As Helen heard the name, she remembered the gossip in the kitchen.

Ceridwen was the pretty sluttish girl, who used to dust under Lady

Warren’s bed, and whose lovers waited for her, outside the house, with

the patient fixity of trees. She believed she had actually seen one of

them in the plantation, whose vigil had certainly proved in vain.

“Rum thing,” said Dr. Parry. “Williams says that when Captain Bean was

coming home from market he lit a match to find the keyhole. That’s how

he chanced to see her—huddled up in a dark corner of his garden. He

came, at once, hell-for-leather to the Bull, and ask Williams to ring my

house. My housekeeper told them to try the Summit.”

“Very shocking,” observed Miss Warren. “I suppose it was some seizure.

Her color was unusually high.”

“I’ll soon find out,” announced Dr. Parry. “What beats me is this. The

Captain’s cottage is only the other side of the plantation. Why didn’t

he come over here, instead of running nearly a mile to the Bull?”

“He had quarrelled with my brother. The Professor pointed out a

scientific slip in one of his articles. And I believe there was trouble

with Mrs. Oates over some of his eggs.”

Dr. Parry nodded with complete comprehension. Captain Bean was a morose

and hot-tempered recluse, who would reject Einstein’s Theory and the

charge of supplying a bad egg with equal fury. He kept a small

poultry-farm, did the work of his cottage, and wrote articles on the

customs and religions of native tribes in unfrequented quarters of the

Globe.

Dr. Parry knew that his life of isolation tended to a lack of

perspective, which would exaggerate a trifling grievance to the

intensity of a feud; and he guessed that he would prefer to plough

through torrential rain rather than ask a neighbor for the use of his

telephone.

“I’ll cut across the plantation,” he said. “It will be quicker. I’ll

come back for my bike.”

The booming of the dinner-gong speeded his parting, but he left a sense

of tragedy behind him. When the family was gathered around the table in

the dining-room, the subject of Ceridwen cropped up with the soup.

Newton and his wife were not interested in the death of a domestic, but

Stephen remembered her.

“Wasn’t she the lass with the little dark come-hither eye and a wet red

mouth?” he asked. “The one Lady Warren coshed?”

“An animal type,” remarked Miss Warren. She hastened to add, in a

perfunctory voice, “Poor girl.”

“Why—poor?” asked Newton aggressively. “We should all envy her. She has

achieved annihilation.”

“‘Healed of her wound of living, shall sleep sound,’” murmured his aunt,

adapting the quotation.

“No!” declared Newton. “No sleep. Too chancey a proposition. One might

wake again. Rather—‘I thank with brief thanksgiving whatever gods there

be, that no life lives forever, that dead men rise up never, that even

the weariest river—’”

“Oh, dry up,” broke in Stephen. “Even a river does that, when it’s been

in the sun.”

“But unfortunately, I am not drunk,” said Newton. “No one could be, in

this house.”

“There’s always the Bull,” Stephen reminded him.

“And a devastating barmaid,” said Simone, with meaningin her voice.

“Oh, Newton knows Whitey all right.” Stephen grinned. “But I’ve cut him

out. I always do that, don’t I, Warren?”

Helen was glad of any interruption, however uncomfortable. It had been

distasteful to listen to a dreary Creed of Negation when every cell in

her body rejoiced in life. What had hurt her even more, was the hint at

a denial of the soul.

Her submerged sense of hostess made Miss Warren rouse herself from her

dream. Although she was unconscious of Stephen’s provocative grin,

Simone’s slanting glances of passion, and Newton’s scowl, she was aware

of some poisoned undertow. She changed the subject, after looking across

at the Professor, who sat with his eyes covered by his hand.

“Is your head aching again, Sebastian?” she asked.

“I hardly slept last night,” he said.

“What are you taking, Chief?” enquired Newton,

“Quadronex.”

“Tricky stuff, Better be careful of your quantities.” A sarcastic smile

flickered round the Professor’s dry lips.

“My dear Newton,” he said, “when you were an infant you squalled so

ceaselessly that I had to administer a nightly sedative, for the sake of

my work. The fact that you survive is proof that I need no advice from

my own son.”

Newton flushed as Stephen burst into a shout of laughter at his expense.

“Thank you for nothing, Chief,” he muttered. “I hope you manage your own

affairs better than you did mine.”

Helen bit her lip as she looked round the table. She reminded herself

that these people were all her ethical superiors. They were

better-educated than herself, and had money and leisure. The Warrens had

intellect and culture, while Simone had travelled, and had knowledge of

the world.

She always sat silent through a meal, since it would require moral

courage for her to take any part in the general conversation. Miss

Warren, however, usually made some attempt to include the help.

“Have you seen any good Pictures, lately?” she asked, choosing a subject

likely to appeal to a girl who never read the Times.

“Only films of general interest,” replied Helen, whose recent visits to

a Cinema had been confined to the free show at Australia House.

“I saw the Sign of the Cross, just before I left Oxford,” broke in

Simone. “I adore Nero.”

The Professor showed some signs of interest.

“Sign of the Cross?” he repeated. “Have they revived that junk? And does

the proletariat still wallow in an orgy of enthusiasm over that symbol

of superstition?”

“Definitely,” replied Simone. “The applause was absurd.”

“Amusing,” sneered the Professor. “I remember seeing the Play—Wilson

Barrett and Maud Jeffries took the leading parts with a,

fellow-undergraduate. This youth was devoted to racing and completely

unreligious. But he developed a sporting interest in the progress of the

Cross. It appealed to him as a winner, and he roared and clapped, in its

scene of ultimate triumph, while the tears rained down his face in his

enthusiasm.”

The general laughter was more than Helen could bear.. Suddenly, to her

own intense surprise, she heard her own voice. “I think

that’s—terrible,” she said shakily.

Everyone stared at her surprised. Her small face was red, and puckered

up, as though she were about to cry.

“Surely a modern girl does not attribute any virtue to a mere symbol?”

asked the Professor.

Helen felt herself shrivelled by his gaze, but’ she would Not recant.

“I do,” she said. “When I left the Convent, in Belgium, the nuns gave

me’ a cross. It always hangs over my bed, and I wouldn’t lose it, for

anything.”

“Why not?” asked Newton.

“Because it stands for—for so much,” faltered Helen.

“What—exactly?”

Helen felt tongue-tied, under the battery of eyes.

“Everything,” she replied vaguely. “And it protects me.”

“Archaic,” murmured the Professor, while his son continued his

catechism.

“What does it protect you from?” he asked.

“From all evil”,

“Then as long as it hung over your bed I suppose you could open your

door to the local murderer?” laughed Stephen.

“Of course not;” declared Helen, for she stood in no awe of the pupil.

“The Cross represents a Power which gave me life. But it gave me

faculties to help me to look after that life for myself.”

“Why, she believes in Providence, too,” said Simone.

“She will tell us next she believes in Santa Claus.” Hard-pressed, Helen

looked around the table. She seemed ringed about with gleaming eyes and

teeth, all laughing at her.

“I only know this,” she declared in a trembling voice, “if I was like

all of you I wouldn’t want to be alive.”

To her surprise, support came from an unexpected quarter, for Stephen

suddenly clapped his hands. “Bravo,” he said. “Miss Capel’s got more

spunk than the lot of us put together. She’s taken us on, five to one,

and she’s only a fly-weight. Hang it all, we ought to be ashamed of

ourselves.”

“It is not a question of courage,” observed the Professor, “but of

muddled thinking and confused value, which is definitely hurtful. You,

Miss Capel, are assuming man to be of Divine origin. In reality, he is

so entirely a creature of appetites and instincts, that—given a

knowledge of this key-interest—anyone could direct his destiny. There

is no such thing as the guidance of Providence.”

Newton thrust his head forward, his eyes gleaming be hind his

spectacles.

“Rather interesting, Chief,” he said. “I’d like to have a shot at

developing a crime picture on those lines. No crude sliding-panels or

clutching hands. Make one character do something which would set the

rest into motion, so that each would do the natural and obvious thing.”

“You have some glimmering of my meaning,” approved his father. “Man is

but clay, animated by his natural lusts.”

Suddenly Helen forgot her subordinate position—forgot that she had a new

job to hold down. She sprang to her feet and pushed back her chair.

“Please excuse me, Miss Warren,” she said, “but I can’t stay—and

listen—”.

“Oh, Miss Capel,” expostulated Newton, “we

Comments (0)