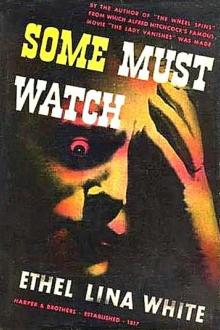

Some Must Watch, Ethel Lina White [crime books to read txt] 📗

- Author: Ethel Lina White

- Performer: -

Book online «Some Must Watch, Ethel Lina White [crime books to read txt] 📗». Author Ethel Lina White

lost its look of immaculate and finished artifice, and crumpled up with

elemental rage.

“I hate you,” she cried furiously. “I hope you’ll go to the dogs and die

in the gutter.”

Rushing from the room, she banged the door behind her. Stephen took a

deep breath and then thumped his chest.

“Thank the pigs,” he said piously.

But the incident left him worried. He wondered whether Simone

contemplated some mean form of revenge. Assuring himself that it was no

good meeting trouble halfway, as on the morrow he would be gone, for

good, he tried to forge this problem in the excitement of a

thrill-novel.

Presently he became aware that his attention was no longer gripped. He

kept raising his eyes from the pages, to listen. Above the howls of the

gale rose a faint whine. It sounded like a dog in distress.

He bit his lip and frowned in perplexity. In spite of his objection, he

realized that the Professor’s precautions were probably sound, and he

was prepared to obey them to the last letter. But, while the Professor

had referred to “man, woman, or child” he had forgotten to include any

animal.

Stephen frowned as he realized that he was up against an acid test. If

this were a trap, some unknown brain had detected his blind spot, and

knew how to exploit it.

“It’s Newton,” he thought. “He’s trying to lure me outside, so I’ll be

shut out. The fool thinks he’s got to protect his wife from me.”

Again the faint howl was borne on the wind, bringing him to his feet.

But again he sat down.

“Hang it,” he muttered aloud. “I won’t. They shan’t get at me. It’s not

fair to risk the women.”

He took up his novel, and tried to concentrate on what he read. But the

lines of print were a meaningless jumble of words, because he was

awaiting—and dreading—a repetition of the cry.

At last, it came—pitiful and despairing, as though the creature were

growing weaker. Unable to sit still, he stole out into the lobby and

unbolted the front door. As he put his head outside, the wind seemed

about to tear off his ears, but it also bore the barking of a dog.

While it might be a faithful animal imitation, there was something

familiar about the sound. Struck by a sudden suspicion, Stephen

cautiously rebolted the door and hurried up to his room.

“Otto,” he caned, as he threw open the door.

But no dog leaped to welcome him. The bed was tidy and the room had been

hurriedly put in order. “The dirty tykes,” he said. “They’ve run him

out. This settles it. I clear out, too.”

Swearing under his breath, he hurriedly changed into his old tweeds and

laced on thick shoes. Bag in hand, he clumped down the back-stairs. No

one saw him, when he crossed the hall, but, as he banged the front door

behind him, Helen heard the slam.

Newton’s visit to his grandmother had released her from her vigil, as

the old lady had ordered her from the room. Although it was her usual

bedtime, Helen decided to break her rule of early hours.

The whole household was upset; while boredom usually drove the family

prematurely to their rooms, they all seemed restless tonight.

Mrs. Oates, also, would be sitting up to let in herusband. Helen felt

she had better share her vigil, in case she should drop off to sleep

again, and miss his ring. She flew to the front door, just in time to

recognize Stephen as he retreated through slanting sheets of rain.

As the light flashed out over the gravel drive, he turned and shouted to

her defiantly:

“Lock up… I’m never coming back.”

Helen hastened to slam the door and re-fasten the bolts.

“Well,” she said. “The young rip.”

She was laughing over the incident when Nurse Barker came up from the

kitchen.

“What was that noise?” she asked suspiciously.

“Mr. Rice has gone,” Helen told her.

“Where?”

“He didn’t tell me, but I can make a pretty good guess. He’s been

terribly keen to go to the Bull, to pay up and say ‘Goodbye’.”

Nurse Barker’s deep-set eyes glinted angrily.

“He’s disobeyed the Professor and risked our safety,” she stormed. “It’s

criminal.”

“No, it’s all right,” Helen assured her. “I locked up after him,

directly. And he’s not coming back.”

Nurse Barker laughed bitterly.

“So it’s all right, is it?” she asked. “Don’t you realize that now we

have lost our two best men?”

WHEN LADIES DISAGREE

As Helen stared at Nurse Barker, she was appalled by the revelation of

her eyes. Anger had given way to a murky gleam of satisfaction, as

though she realized the weakening of the defence.

Remembering that she was marked out for distinctive bait, the knowledge

inspired the girl with defiance.

“We’ve still two men,” she said. “And, five women—all able-bodied and

strong.”

“Are you strong?” asked Nurse Barker, sneering down at Helen, from her

superior height.

“I’m young.”

“Yes, you’re young. You may remember that—before you’re much older.

And—perhaps—you may regret your youth.”

Helen tossed back her red mane impatiently.

“I suppose the Professor ought to be told about Mr. Rice,” she said.

“And, of course, you will tell him.”

“Why—me?” asked Helen.

“He’s a man.”

“Look here, Nurse,” Helen said, in her mildest voice, “I think that

bickering, just now, is silly. We all want to pull together. We don’t

want to keep harping on men. And I’m sure you don’t want me to be the

next victim. You’re too good a sport.”

“I have no ill-feeling towards you,” Nurse Barker assured her in a

muffled voice.

“Good,” said Helen. “When you go up to Lady Warren, will you tell Mr.

Newton what’s happened, and ask him to let his father know.”

Nurse Barker bowed her head, in stately assent, and began to mount the

staircase. Helen stood in the hall, watching her flat-footed ascent, as

the tall white figure gradually towered above her.

“You can wear high Spanish heels, when you’re small,” she thought,

looking down, with satisfaction, at her own feet. “She walks just like a

man.”

She noticed that, as Nurse Barker retreated, she apappeared little more

than a dim glimmer crossing the dimly-lit landing, as though some

ghostly shape were rising from its churchyard bed. The illusion reminded

her of her own experience, before dinner, when she had been appalled by

a momentary vision of evil.

“It must have been the Professor,” she assured herself.

“I fancied the rest.”

Suddenly she remembered, an additional detail. The Professor had emerged

from his bedroom, whereas she had another recollection of a door being

opened and then shut immediately.

“Odd,” she thought. “The Professor wouldn’t open his door, and then,

slam it—and then open it again. There’s no sense in that.”

Staring up at the landing, she noticed that the door of the Professor’s

bedroom was close beside that of the back staircase. Someone might have

looked out from the one, just as the other was opening, with the

meticulous timing of a lucky chance.

The notion was not only absurd, but so disquieting that Helen refused to

admit it.

“No one could have got into the house,” she told herself. “It was all

locked up, when Ceridwen was strangled… But, supposing there was

some secret way in, of course the murderer could have rushed from the

plantation and been lurking on the back-stairs, when I saw him…

Only, it was the Professor.”

In spite of the seeming impossibility of anyone entering the fortress,

she began to wonder, if—for a minute or soany chink had been left in

the defense. At the back of her mind, something was worrying her…

Something forgotten—or overlooked.

She had been unmethodical, all the evening, breaking off in the middle

of a job to start another. For example, she had not even begun to screw

up the handle of Miss Warren’s bedroom door. Before she had discovered

how to tackle the difficulty, she had been interrupted by the Professor,

and left her tools lying on the landing.

“Anyone might think I was untidy,” she thought. “I’ll go up again and

experiment a bit.”

As the resolution crossed her mind, it was swept aside by the spectacle

of Newton, hurrying down the stairs. His sallow face was flushed with

excitement, as he spoke to her.

“So the noble Rice has walked out on us?”

“Yes,” replied Helen. “I was there when he went—and I locked him out.”

“Good… I suppose he was alone?”

“I only saw him on the drive. But it was very dark and confusing in the

rain.

“Quite.” Newton’s eyes flickered behind his glasses. “Do you mind

waiting here, just for a minute?”

Helen knew what was in his mind as he galloped upstairs to the second

floor, and she smiled over his ground less fear, even while she knew

that she could have saved him his journey, at the expense of tact.

A minute later, he clattered down again, ostentatiously flourishing a

clean handkerchief, to excuse his flight.

“My wife is a bit upset,” he remarked casually. “Headache, and so on.

Perhaps you’d see if you could do something for her, when you’ve time?”

“Certainly,” promised Helen.

Newton’s smile was so unexpectedly boyish, that Helen understood the

secret of his popularity with his womenkind.

“What a lot we Warrens expect for our money,” he said. “I do hope you

get a decent salary. You earn it… Now, we must tell the Chief

about Rice.”

Once again, Helen was flattered at being asked to help him. Although her

sympathies were with Stephen, she had infinitely more respect for

Newton. All the men seemed to be inviting her co-operation, that night;

instead of being in the background, she was constantly on the boards.

It was true that she was there, chiefly to feed the principals, and was

not picked out by the limelight; but, in the circumstances, it seemed

safer not to advertise. She even congratulated herself that Nurse Barker

was not present to witness her entrance into the study, since personal

tri umph was not worth more friction.

The Professor was lying back in his chair, with his eyes closed, as

though in concentration. He did not open his lids, until Newton called

his name. When he did so, Helen thought that his pupils looked curiously

fixed and glassy.

Apparently, Newton shared her impression.

“Been mopping up the quadronex?” he asked.

The Professor’s stare reproved the impertinence.

“As I’m the financial head of this house,” he observed, “I have to

conserve my strength, for the benefit of my—dependents. I must insure

some sleep, tonight… Have you anything to tell me?”

His lips tightened as he listened to Newton’s news.

“So. Rice rebelled against my restrictions?” he said. “That young man

may develop into a good citizen, ultimately, but, at present, I fear he

is a Goth.”

“I should call him a bad relapse,” remarked Newton.

“Still, he was a hefty barbarian,” his father reminded him. “In his

absence, Newton, you and Ihave more to do.”

“Which means myself, Chief. You’re a bit past tackling a maniac.”

Helen guessed that the Professor was irritated by the remark.. “My

brain remains at your service,” he ‘said. “Unfortunately, I was only

able to pass on a section of it to my son.”

“Thanks, Chief,

Comments (0)