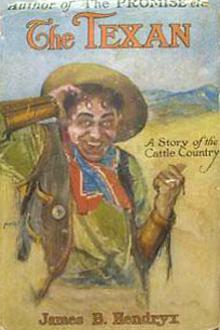

The Texan, James B. Hendryx [ebook and pdf reader TXT] 📗

- Author: James B. Hendryx

- Performer: -

Book online «The Texan, James B. Hendryx [ebook and pdf reader TXT] 📗». Author James B. Hendryx

About the wreck torches flared and the night was torn by the clang and rattle of gears as the great crane swung a boxcar to the side. The single street was filled with people—women and men from the wagons, and cowboys who dashed past on their horses or clumped along the wooden sidewalk with a musical jangle of spurs.

The dance-hall was a blaze of light toward which the people flocked like moths to a candle flame. As they pushed the horses past, the girl glanced in. Framed in the doorway stood a man whose eyes met hers squarely—eyes that, in the lamplight seemed to smile cynically as they strayed past her and rested for a moment upon her companion, even as the thin lips were drawn downward at their corners in a sardonic grin.

Unconsciously she brought her quirt down sharply, and her horse, glad of the chance to stretch his legs after several days in the stall, bounded forward and taking the bit in his teeth shot past the little cluster of stores and saloons, past the straggling row of houses and headed out on the trail that wound in and out among the cottonwood clumps of the valley. At first, the girl tried vainly to check the pace, but as the animal settled to a steady run a spirit of wild exhilaration took possession of her—the feel of the horse bounding beneath her, the muffled thud of his hoofs in the soft sand of the trail, the alternating patches of moonlight and shadow, and the keen tang of the night air—all seemed calling her, urging her on.

At the point where the trail rose abruptly in its ascent to the bench, the horse slackened his pace and she brought him to a stand, and for the first time since she left the town, realized she was not alone. The realization gave her a momentary start, as Purdy reined in close beside her; but a glance into the man's face reassured her.

"Oh, isn't it just grand! I feel as if I could ride on, and on, and on."

The man nodded and pointed upward where the surface of the bench cut the sky-line sharply.

"Yes, mom," he answered respectfully. "If yeh'd admire to, we c'n foller the trail to the top an' ride a ways along the rim of the bench. If you like scenes, that ort to be worth while lookin' at. The dance won't git a-goin' good fer an hour yet 'til the folks gits het up to it."

For a moment Alice hesitated. The romance of the night was upon her. Every nerve tingled, with the feel of the wild. Her glance wandered from the rim of the bench to the cowboy, a picturesque figure as he sat easily in his saddle, a figure toned by the soft touch of the moonlight to an intrinsic symbolism of vast open spaces.

Something warned her to go back, but—what harm could there be in just riding to the top? Only for a moment—a moment in which she could feast her eyes upon the widespread panorama of moonlit wonder—and then, they would be in the little town again before the dance was in full swing. In her mind's eye she saw Endicott's disapproving frown, and with a tightening of the lips she started her horse up the hill and the cowboy drew in beside her, the soft brim of his Stetson concealing the glance of triumph that flashed from his eyes.

The trail slanted upward through a narrow coulee that reached the bench level a half-mile back from the valley. As the two came out into the open the girl once more reined her horse to a standstill. Before her, far away across the moonlit plain the Bear Paws loomed in mysterious grandeur. The clean-cut outline of Miles Butte, standing apart from the main range, might have been an Egyptian pyramid rising abruptly from the desert. From the very centre of the sea of peaks the snow-capped summit of Big Baldy towered high above Tiger Ridge, and Saw Tooth projected its serried crown until it seemed to merge into the Little Rockies which rose indistinct out of the dim beyond.

The cowboy turned abruptly from the trail and the two headed their horses for the valley rim, the animals picking their way through the patches of prickly pears and clumps of low sage whose fragrant aroma rose as a delicate incense to the nostrils of the girl.

Upon the very brink of the valley they halted, and in awed silence

Alice sat drinking in the exquisite beauty of the scene.

Before her as far as the eye could see spread the broad reach of the Milk River Valley, its obfusk depths relieved here and there by bright patches of moonlight, while down the centre, twisting in and out among the dark clumps of cottonwoods, the river wound like a ribbon of gleaming silver. At widely scattered intervals the tiny lights of ranch houses glowed dull yellow in the distance, and almost at her feet the clustering lights of the town shone from the open windows and doors of buildings which stood out distinctly in the moonlight, like a village in miniature. Faint sounds, scarcely audible in the stillness of the night floated upward—the thin whine of fiddles, a shot now and then from the pistol of an exuberant cowboy sounding tiny and far away like the report of a boy's pop-gun.

The torches of the wrecking crew flickered feebly and the drone of their hoisting gears scarce broke the spell of the silence.

Minutes passed as the girl's eyes feasted upon the details of the scene.

"Oh, isn't it wonderful!" she breathed, and then in swift alarm, glanced suddenly into the man's face. Unnoticed he had edged his horse close so that his leg brushed hers in the saddle. The hat brim did not conceal the eyes now, that stared boldly into her face and in sudden terror the girl attempted to whirl her horse toward the trail. But the man's arm shot out and encircled her waist and his hot breath was upon her cheek. With all the strength of her arm she swung her quirt, but Purdy held her close; the blow served only to frighten the horses which leaped apart, and the girl felt herself dragged from the saddle.

In the smoking compartment of the Pullman, Endicott finished a cigarette as he watched the girl ride toward the town in company with Purdy.

"She's a—a headstrong little fool!" he growled under his breath. He straightened out his legs and stared gloomily at the brass cuspidor. "Well, I'm through. I vowed once before I'd never have anything more to do with her—and yet—" He hurled the cigarette at the cuspidor and took a turn up and down the cramped quarters of the little room. Then he stalked to his seat, met the fat lady's outraged stare with an ungentlemanly scowl, procured his hat, and stamped off across the flat in the direction of the dance-hall. As he entered the room a feeling of repugnance came over him. The floor was filled with noisy dancers, and upon a low platform at the opposite end of the room three shirt-sleeved, collarless fiddlers sawed away at their instruments, as they marked time with boots and bodies, pausing at intervals to mop their sweat-glistening faces, or to swig from a bottle proffered by a passing dancer. Rows of onlookers of both sexes crowded the walls and Endicott's glance travelled from face to face in a vain search for the girl.

A little apart from the others the Texan leaned against the wall. The smoke from a limp cigarette which dangled from the corner of his lips curled upward, and through the haze of it Endicott saw that the man was smiling unpleasantly. Their eyes met and Endicott turned toward the door in hope of finding the girl among the crowd that thronged the street.

Hardly had he reached the sidewalk when he felt a hand upon his arm, and turned to stare in surprise into the dark features of a half-breed,—the same, he remembered, who had helped the Texan to saddle the outlaw. With a swift motion of the head the man signalled him to follow, and turned abruptly into the deep shadow of an alley that led along the side of the livery bam. Something in the half-breed's manner caused Endicott to obey without hesitation and a moment later the man turned and faced him.

"You hont you 'oman?" Endicott nodded impatiently and the half-breed continued: "She gon' ridin' wit Purdy." He pointed toward the winding trail. "Mebbe-so you hur' oop, you ketch." Without waiting for a reply the man slipped the revolver from his holster and pressed it into the astonished Endicott's hand, and catching him by the sleeve, hurried him to the rear of the stable where, tied to the fence of the corral, two horses stood saddled. Loosing one, the man passed him the bridle reins. "Dat hoss, she damn good hoss. Mebbe-so you ride lak' hell you com' long in tam'. Dat Purdy, she not t'ink you got de gun, mebbe-so you git chance to kill um good." As the full significance of the man's words dawned upon him Endicott leaped into the saddle and, dashing from the alley, headed at full speed out upon the winding, sandy trail. On and on he sped, flashing in and out among the clumps of cottonwood. At the rise of the trail he halted suddenly to peer ahead and listen. A full minute he stood while in his ears sounded only the low hum of mosquitoes and the far-off grind of derrick wheels.

He glanced upward and for a moment his heart stood still. Far above, on the rim of the bench, silhouetted clearly against the moonlight sky were two figures on horseback. Even as he looked the figures blended together—there was a swift commotion, a riderless horse dashed from view, and the next moment the sky-line showed only the rim of the bench.

The moon turned blood-red. And with a curse that sounded in his ears like the snarl of a beast, Winthrop Adams Endicott tightened his grip upon the revolver and headed the horse up the steep ascent.

The feel of his horse labouring up the trail held nothing of exhilaration for Endicott. He had galloped out of Wolf River with the words of the half-breed ringing in his ears: "Mebbe-so you ride lak' hell you com' long in tam'!" But, would he "com' long in tam'"? There had been something of sinister portent in that swift merging together of the two figures upon the sky-line, and in the flash-like glimpse of the riderless horse. Frantically he dug his spurless heels into the labouring sides of his mount.

"Mebbe-so you kill um good," the man had said at parting, and as Endicott rode he knew that he would kill, and for him the knowledge held nothing of repugnance—only a wild fierce joy. He looked at the revolver in his hand. Never before had the hand held a lethal weapon, yet no slightest doubt as to his ability to use it entered his brain. Above him, somewhere upon the plain beyond the bench rim, the woman he loved was at the mercy of a man whom Endicott instinctively knew would stop at nothing to gain an end. The thought that the man he intended to kill was armed and that he was a dead shot never entered his head, nor did he remember that the woman had mocked and ignored him, and against his advice had wilfully placed herself in the man's power. She had harried and exasperated him beyond measure—and yet he loved her.

The trail grew suddenly lighter. The walls of the coulee flattened into a wide expanse of open. Mountains loomed in the distance and in the white moonlight a riderless horse ceased snipping grass, raised his head, and with ears cocked forward, stared at him. In a fever of suspense Endicott gazed about him, straining his eyes to penetrate the half-light, but the plain stretched endlessly away, and upon its surface was no living, moving thing.

Suddenly his horse pricked his ears and sniffed. Out of a near-by depression that did not show in

Comments (0)