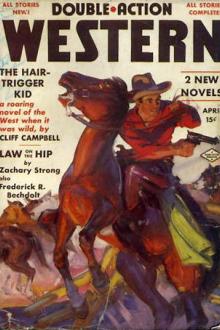

The Hair-Trigger Kid, Max Brand [best classic literature TXT] 📗

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid, Max Brand [best classic literature TXT] 📗». Author Max Brand

“That’s the only water,” nodded the girl. “They’re herding the

cows back from the creek and putting up a line fence on each side.”

“Dixon and Shay,” nodded the Kid.

“How do you guess at Shay, too?”

“I’ve heard that they’re working together. Dixon turns the

rabbit, and Shay eats it. They make a pretty neat pair, working

together.”

“There’s another man coming,” she said, pointing to a horseman who had

just bobbed into sight in the far distance, in the same direction from

which the Kid had come on his hunt.

“That’s my partner,” said the Kid, without looking. “But you never have

partners,” said the girl.

“I’ve changed my ways,” he declared briefly. “Are you going to dynamite

Dixon and his men? How many has he?”

“Something more than fifteen. About twenty, I think.”

“That’ll take some blasting. I know the kind of fellow he’d pick for

company on a job like that.”

“He’s got ‘em,” said the girl. “Well, I’ll drift along. I’ve still got a

stretch ahead of me.”

“If I can be any help,” said the Kid suddenly, “give me a call.”

She jerked in the reins so quickly and so hard that the gelding reared,

and then landed prancing.

She paid no attention to this. She sat the saddle like a man, conscious

of strength, and unafraid.

“What do you mean by that?” she asked. “Help us against Dixon and his

lot?”

“If there’s to be a game,” said the Kid lightly, “I might as well sit in

for a hand or two.”

She stared at him.

“Would you do that just for the fun of it?” she asked him. “You see how

it is,” said the Kid. “That would give us an excuse to camp in one spot

until we’d cleaned up this venison. Otherwise, a lot of it will go to

waste.”

She, watching him curiously, could not help asking: “Is there anything in

the world that could make you take care of your neck?”

“I carry a thousand dollars’ insurance,” said the Kid. “You can’t expect

a man to do more than that.”

She laughed heartily, and said:

“D’you seriously mean that you’ll help us?”

“I’ll shake on it,” said the Kid, extending his hand.

She moved her own, then jerked it away.

“No,” she said, shaking her head. “I don’t think I have a right to tie

you down to a promise. But if you’ll go back there to the ranch house and

tell Mother that you’re a little interested, she’ll think you’re an angel

newly out of heaven!”

When Mrs. Milman had finished her second promenade between the house and

the woods, walking with a quick, eager step, she was no closer to a

solution of the problem than before. She knew that the ranch was

confronted by the most imminent danger of destruction. And the place

meant something more than dollars to her. Sometimes her mind turned

quickly toward her husband, now far off trying to bring guns to help

them, but her confidence in her spouse was not great. He was made of too

mild a metal to cut through to the heart of such a problem as this.

And for her own part?

She measured out her way with the same brisk steps, her head high, using

a long stick for a cane like one of those dainty great ladies of the old

century who had played at dairy maids in the woods of the Trianon.

She had completed her second round when, pausing by the verge of the

woods, she watched two horsemen coming up the slope, one on a sorrel and

one on a black with a white breast. Men and horses were about of a size,

she decided, but the black had a way of going that made his rider appear

small and light. He danced up that hill as though a mere form of paper

were in the saddle on his back. Somewhere before she felt that she had

seen that horse.

She was an expert in horses, but she was a still greater expert in men,

and that rider of the black horse had a way of holding up his head that

pleased her. It was, in short, like her own, though this did not come

into her mind.

The pair of strangers were well up to the top of the rise, and coming in

between the wood shed and the feeding corral before she recognized the

Kid, and her heart leaped. For she was, as has been said, a connoisseur

of men. Besides. she could remember how that single man had entered the

house of Billy Shay, and how fugitives had begun to appear at its doors

and windows, as though thrust out by an explosion.

Suppose such a man were applied to the affair down there at the creek.

But no! He was far more apt to be in the employ of Champ Dixon, that wily

cutthroat.

She waved her stick as they came closer and the Kid, seeing her, turned

instantly in her direction. Lightly as a dancer, the Duck Hawk came on,

flicking the dust behind her. Then the Kid swung down to the ground and

took off his hat. Bud Trainor, behind him, and a little to the side, did

the same thing.

“Are you Mrs. Milman?” said the Kid.

“Yes,” said she. “Have you seen me before?”

“I simply guessed,” said he. “I was looking for the lady of the house.

This is my friend, Bud Trainor.”

Here Bud mumbled something, downfaced, for Elinore Milman was several

cuts above the people of his familiar world. “And I’m called the Kid, by

most people.”

“I saw you calling on Mr. Shay in Dry Creek,” said she. “Oh, yes. An old

friend of mine,” said the Kid.

“You’ll let me call you something beside ‘Kid,’ I hope,” said she.

“My real name,” he answered, “is Reginald Beckwith-Hollis, with a hyphen.

That’s why people call me the Kid. The real name takes up so much time.”

She permitted her eyes to smile, and the Kid grinned gayly back at her.

“Are you just passing through, Mr. Beckwith-Hollis?” she asked him.

“I was just passing through,” said the Kid. “But something stopped me.”

“Champ Dixon and his boys at Hurry Creek?” she asked.

“No,” said the Kid. “I’m not playing this hand with them.” She sighed

with relief.

“I met your daughter,” said he.

Mrs. Milman gripped her stick a little harder and looked more closely at

that handsome, boyish, careless face.

“Ah, you met Georgia?” said she.

“Yes. She was signing up recruits, and we joined. She sent us here to

report to you.”

“Georgia is a good recruiting agent, then,” said she. “What terms did she

offer?”

“We didn’t talk of that,” said the Kid. “What d’you suggest?”

She looked away from him across the hills, and noted the steady drift of

cattle heading toward Hurry Creek. Before long, all the cattle on the

place would be gathered in vast, milling throngs which would stamp the

turf to dust near the water, and that dust would quicken the pangs of

thirst. She could visualize hundreds, thousands lying down to die under

the hot sun. And how hot it was. It burned through the shoulders of her

dress. It scorched her hand through the thin glove which she was wearing.

Then she made up her mind.

“The minute that the Dixon gang is driven off—to stay,” said she,

“you’ll get a check for ten thousand dollars. You can split that with Mr.

Trainor any way you see fit.”

Bud Trainor glanced up as though the heavens had opened. But the Kid,

still smiling a little, shook his head.

“We’re only here for a short job,” said he. “We’ll work for two dollars a

day—and keep, if that’s agreeable to you?” She stared at him.

“You don’t want money Mr.—Beckwith-Hollis?”

“Certain kinds, I can get along without.”

She turned suddenly upon Bud Trainor.

“And what about you?” she asked.

Bud started eagerly to reply. He had heard a fortune named. He had seen

his start in life presented as on a golden salver. But then he remembered

in what company he was traveling. He cast a sidelong look at the Kid and

muttered: “The Kid does my thinking for me on this trip.”

Mrs. Milman confronted the Kid again.

“I don’t understand you,” she said bluntly. “Of course, it’s generous.

But to drive out the Dixon outfit will mean risking your life! Is there

something else that you want?”

The Kid smiled upon her with his utmost geniality.

“I’ll tell you how it is,” said he. “A man doesn’t like to make

money outside of his regular trade. That’s the way with me, I suppose.”

“And what is your regular trade?” said she.

“It has several branches,” he answered her. “You might call me a miner. I

use a pack of cards for powder when I’m breaking ground.”

“You mean that you’re a gambler?”

“Yes. That’s my main line.”

“And that leaves you—scruples”—she hesitated for words—“about making

money in this way?”

“Yes,” said he. “I have scruples. Behind Dixon is Billy Shay. And Billy

Shay took a friend of mine into camp, one day. He started on a trip with

my partner. He finished the trip alone, and the other fellow never was

heard of. You see, this job of yours is my job, as well, because Shay’s

on the other side of fence from you.”

“Does that go for your friend, too?”

She nodded toward Trainor.

“We’re thrown in together,” said the Kid. “All for one and one for all.

Is that all clear, now?”

She paused again.

“It’s not clear at all,” said she, “but if you want to have it this way,

heaven knows how glad I am to have you helping us. Have you any plans?”

“Not a plan in the world.”

“You don’t know how you’re going to begin?”

“Why, I suppose that we ought to wait to see how the recruits turn in

from the ranches around here.”

“Do you think that they’ll come in?” she asked.

“What do you think?”

“I believe they won’t.”

“I agree with you.”

“Why do you?”

“Because Dixon seems to have a bit of law behind him. And the only way to

save your cows is going to be to forget that such a thing as law exists.”

The smile died from his eyes. He looked at her as straight as a ruled

line; and she looked hack, her color gradually ebbing from her face.

“Bud,” said the Kid, “suppose that you take the hoses and give ‘em a

swallow of water over there at the trough.”

Bud nodded, and taking the horses by the bridles, he led them away.

“Thank you,” said Mrs. Milman. “I wanted to talk to you alone.”

The Kid nodded. “I thought so,” said he.

He was as grave as before, waiting.

“Don’t you think,” said she, “that we’ll get on a lot better if we talk

frankly to one another.”

“Don’t you think,” said the Kid, “that there’s nobody in the world that

any one in it can talk frankly to?”

“Husbands and wives, even, and parents and children?” she suggested.

“Well,” said the Kid, his old smile glimmering at her,

Comments (0)