Spinifex and Sand<br />A Narrative of Five Years' Pioneering and Exploration in Western Ausralia, David Wynford Carnegie [best novels in english .txt] 📗

- Author: David Wynford Carnegie

Book online «Spinifex and Sand<br />A Narrative of Five Years' Pioneering and Exploration in Western Ausralia, David Wynford Carnegie [best novels in english .txt] 📗». Author David Wynford Carnegie

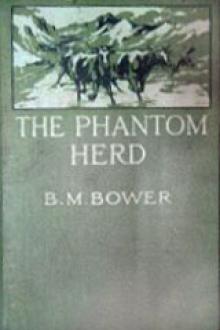

Breaden and I set to work to unload the camels while the others started preparations for water-getting. By 3 p.m. we were ready. King Billy at the bottom, baling water with a meat tin into a bucket, which he handed to Warri, who passed it to Charlie; thence via Godfrey it reached Breaden, who on the floor of the cave hitched it on to a rope, and I from above hauled it through the entrance to the surface. Useful as he was below, I soon had to call Warri up to keep off the poor famished camels, who, in their eagerness, nearly jostled me into the hole. First I filled our tanks, doubtful what supply the cave would yield; but when word was passed that “She was good enough, and making as fast as we baled,” I no longer hesitated to give the poor thirsty beasts as much as ever they could drink. What a labour of love that was, and what satisfaction to see them “visibly swelling” before my eyes! Till after sunset we laboured unceasingly, and I fancy none of us felt too strong. The thundery weather still continued; the heat was suffocating—so much so that I took off my hat and shirt, to the evident delight of the flies, whose onslaughts would have driven me mad had I not been too busily engaged to notice them.

Before night all the camels were watered; they drank on an average seventeen gallons apiece, and lay gorged upon the ground too tired or too full of liquid to eat. We had a very different camp that night, and King Billy shared our good spirits. Now that he had his liberty he showed no signs of wishing to leave us, evidently enjoying our food and full of pride in his newly acquired garment, a jersey, which added greatly to his striking appearance. He took great interest in all our belongings, but seemed to value highest the little round piece of metal that is fixed on the inside of a meat-tin! This, hung on a string, made a handsome ornament for him.

That night, in reviewing our affairs, I came to the conclusion that this dry stage at the beginning of our journey had been a good thing for all. We had had a bad time, but had come out of it all right. Although these things always appear worse, when written or read, yet it is no light task to trudge day after day over such horrible country with an empty stomach and dry throat, and with no idea of when the next water will be found, or if any will be found; and through it all to be cheerful and good-tempered, and work away as usual, as if all were right. It had inspired us with complete confidence in the staying powers of the camels, who, in spite of a thirteen and a half days' drought, had shown no signs of giving in. It had afforded each of us an insight into the characters of his companions that otherwise he never would have had. It had given me absolute confidence in Breaden, Godfrey, and Charlie, and I trust had imbued them with a similar faith in me.

August 11th to 15th we rested at the cave, occupying ourselves in the numerous odd jobs that are always to be found, happy in the knowledge that we had an unfailing supply of water beneath us. I have little doubt but that this water is permanent, and do not hesitate to call it a spring. I know well that previous travellers have called places “springs” which in after years have been found dry; but I feel sure that this supply so far, nearly sixty feet, below the surface, must be derived from a permanent source, and even in the hottest season is too well protected to be in any way decreased by evaporation.

Illustration 16: At work in the cave, Empress Spring

As a humble tribute to the world-wide rejoicings over the long reign of our Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria, I have honoured this hidden well of water by the name of “The Empress Spring.” A more appropriate name it could not have, for is it not in the Great Victoria Desert? and was it not in that region that another party was saved by the happy finding of Queen Victoria Spring?

The “Empress Spring” would be a hard spot to find. What landmarks there are I will now describe. My position for the Spring is lat. 26° 47´ 21´´S., long. 124° 25´E. Its probable native name (I say probable because one can never be sure of words taken from a wild aboriginal, who, though pointing out a water, may, instead of repeating its name, be perhaps describing its size or shape) is “Murcoolia Ayah Teenyah.” The entrance is in a low outcrop of magnesian limestone, surrounded by buckbush, a few low quondongs and a low, broom-like shrub; beyond this, mulga scrub. Immediately to the North of the outcrop runs a high sand-ridge, covered sparsely with acacia and spinifex. On the top of the ridge are three conspicuously tall dead mulga trees. From the ridge looking West, North, North-East, and East nothing is visible but parallel sand-ridges running N.E. To the South-West can be seen the high ground on which is the rock-hole (Mulundella).

To the South-East, across a mulga-covered flat, is a high ridge one mile distant, with the crests of others visible beyond it; above them, about twelve miles distant, a prominent bluff (Breaden Bluff), the North end of a red tableland. From the mulga trees the bluff bears 144°. One and a half miles N.E. by N. from the cave is a valley of open spinifex, breaking through the ridges in a West and Southerly direction, on which are clumps of cork-bark trees; these would incline one to think that water cannot be far below the surface in this spot.

Close to the entrance to the cave is erected a mulga pole, on which we carved our initials and the date. There are also some native signs or ornaments in the form of three small pyramids of stones and grass, about eight feet apart, in a line pointing S.W.

Several old native camps were dotted about in the scrub; old fires and very primitive shelters formed of a few branches. Amongst the ashes many bones could be seen, particularly the lower maxillary of some species of rat-kangaroo. To descend to the cave beneath, the natives had made a rough ladder by leaning mulga poles against the edge of the entrance from the floor. All down the passage to the water little heaps of ashes could be seen where their fires had been placed to light them in their work. Warri found some strange carved planks hidden away in the bushes, which unfortunately we were unable to carry. King Billy saw them with evident awe; he had become very useful, carrying wood and so forth with the greatest pleasure. The morning we left this camp, however, he sneaked away before any of us were up. I fancy that his impressions of a white man's character will be favourable; for never in his life before had he been able to gorge himself without having had the trouble of hunting his food. From him I made out the following words, which I consider reliable:—

English Aboriginal Smoke, fire Warru or wallu Wood Taalpa Arm Menia Hand Murra Hair Kuttya Nose Wula or Ula Water Gabbi Dog Pappa* * This word “pappa” we found to be used by all natives encountered by us in the interior. Warri uses it, and Breaden tells me that in Central Australia it is universal.August 15th we again watered the camels, who were none the worse for their dry stage. Breaden was suffering some pain from his strain, and on descending to the cave was unable to climb up again; we had some difficulty in hauling him through the small entrance.

CHAPTER VI Woodhouse LagoonBut for the flies, which never ceased to annoy us, we had enjoyed a real good rest, and were ready to march on the morning of the 16th, no change occurring in the character of the country until the evening of the 18th, when we sighted a low tableland five miles to the North, and to the West of it a table-topped detached hill. Between us and the hills one or two native smokes were rising, which showed us that water must be somewhere in the neighbourhood. From a high sandhill the next morning, we got a better view, and could see behind the table-top another and similar hill. I had no longer any doubt as to their being Mounts Worsnop and Allott (Forrest, 1874), the points for which I had been steering, though at first they appeared so insignificant that I hesitated to believe that these were the right ones. From the West, from which direction Forrest saw them first, they appear much higher, and are visible some twenty miles off. From the North they are not visible a greater distance than three miles, while from the East one can see them a distance of eight miles.

I altered our course, therefore, towards the hills, and we shortly crossed the narrow arm of a salt-lake; on the far side several tracks of emus and natives caught my eye, and I sent Charlie on Satan to scout. Before long he reported a fine sheet of water just ahead. This, as may be imagined, came as a surprise to us; for a more unlikely thing to find, considering the dry state of the rock-holes we had come upon, could not have been suggested. However, there it was; and very glad we were to see it, and lost no time in making camp and hobbling the camels. What a glorious sight in this parched land!—so resting to the eye after days of sand! How the camels wallowed in the fresh water! how they drank! and what a grand feed they had on the herbage (Trichinium alopecuroideum) on the banks of the lagoon! Charlie and I spent the afternoon in further exploring our surroundings, and on return

Comments (0)