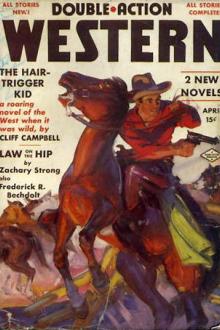

The Hair-Trigger Kid, Max Brand [best classic literature TXT] 📗

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid, Max Brand [best classic literature TXT] 📗». Author Max Brand

considered except when they are really funny. But the staple Western

story is one which clings so closely to the truth throughout most of its

telling, that the embroidering of the main truth with fancy in the vital

point of the tale will be overlooked by the listener. If only one shot is

fired, there is no good reason why two Indians, Mexicans, or thugs should

not be in line with its flight; but the narrator is sure to express

astonishment before he tries to arouse yours, and he will carefully

explain, with a false science, just how the odd position came about.

There is the story-teller who never speaks in his own person, too. All of

his stories begin, end, and are supported in the middle by “they say.”

“They” of “they say” is a strange creature. It has the flight of a falcon

and the silent wings of a bat; it speaks the language of the birds and

bees; it can follow the snake down the deepest hole, and then glide like

a magic ray through a thousand feet of solid rock; it can penetrate

invisibly into houses through the thickest walls, in order to see strange

crimes; it can step through the walls of the most secretive mind in order

to read strange thoughts. “They” has the speed of lightning, and leaps

here and there to pick up grains of information, like a chicken picking

up worms in a newly turned garden; “they” throws a girdle around the

world in a fortieth of Puck’s boasted time. Those who quote “they,” who

quote and follow and mystically adore and believe in “they,” sometimes do

so with awe-stricken whispers, but there are some who sneer at their

authority, and shrug their shoulders at the very stories they relate.

Such people, when questioned, yawn and shake their heads.

“I dunno. That’s what ‘they’ say.”

You can take your choice. Believe it or not. Most people choose to

believe, and therefore the rare information of “they,” thrice, yes, and

thirty times watered and removed, is repeated over and over until it

becomes a mist as tall as the moon and as thin as star dust.

There were gossips of every school in the crowd that poured into Shay’s

house. The moment that they drew open the front door, they found a scene

which was interesting enough to charm them all.

The furniture which first had been piled against the door to secure this

point against the entrance of the Kid, was now cast helter-skelter back

against the walls. Much of it was broken. The legs of chairs seemed

knocking together, or else they bowed perilously out. And one chair, as

if it had taken wings, had become entangled in the good, strong chains

which suspended the hall lamp near the door. For this was a very

pretentious house.

Some strong hand had flung that chair!

No wonder that chars had been thrown, though. For the ceiling, the floor,

the walls, were ripped and plowed by many bullets. It looked as though

half a dozen cartridge belts had been emptied here alone.

And at the foot of the stairs lay “Three-card” Alec, who no longer

groaned, but had braced himself with his shoulders on the lower stair.

His right leg extended before him with a painful ‘crookedness, but he had

a cigarette between his fingers, and he was smoking with deep, almost

luxurious breaths, his eyes half closed. For “the makin’s” is a greater

thing in the West than whisky, chewing tobacco, and chloroform all rolled

into one.

The crowd, entering, looked about with awe at that wrecked and ruined

hallway. Turning, they could stare straight through the front wall of the

house and see the little, white, round patches of daylight that streamed

through the bullet holes. A long strip of plaster, loosened by raking

shots from the ceiling of the hall, fell now with a noisy crash.

Some people grew afraid, and would not enter the place, even with such a

crowd. There was a baneful influence still in the air, and the odor of

gunpowder was severe in every room and hall from the cellar to the attic.

“Is there anybody else in the house?” asked the sheriff of the gambler.

“Say, whadya think?” replied Three-card Alec sneeringly. The sheriff went

on by him.

So did every one else, waiting for the “other fellow” to take charge of

the hurt man. The “other fellow” is well nigh as ubiquitous and certainly

of far better character than “they.”

No one went near poor Three-card Alec to help him, until Georgia Milman

squatted beside him and looked into his narrow, beady, winking, uncertain

eyes.

Three-card looked like a bird—and a very bad bird, at that. His nose was

long enough to make a handle for his whole face. Behind it his face

receded toward the hair and toward the chin. The latter feature hardly

mattered, and the face flowed smoothly, with hardly a ripple, into the

throat. Three-card had two big buckteeth. Like all buckteeth, they were

kept scrupulously white, but they looked, somehow, like the upper part of

a parrot’s beak. His mouth was generally half open, and he had the look

of being about to give something a good hard peck. Three-card had little,

overbright, shifty eyes; and he had a yellowish skin, and on his receding

brow there were a maze of lines of trouble, pain, greed and envy. His

body was as bad as his face, for it was starved, crooked, hollow-chested,

weak-backed, humped, skinny, and generally half deformed. His only

redeeming feature was his hands, and these were beautiful objects for

even a casual eye to rest upon. They were graceful, long, slender and

white—which proved that they were kept scrupulously gloved except when

there was a need of them in action. Those delicate and nervous hands of

Three-card were in fact his fortune, whether they were employed with

cards, dice, the handle of a knife, or on the grip of a revolver.

Three-card was only a wicked caricature of a man. There was hardly any

good about him, but he had been brave as he was wicked, and therefore he

was respected in a certain way.

Georgia merely said: “Is it pretty bad?”

For reply he stared at her and puffed on his cigarette again. There was

no decent courtesy in Three-card.

“Do you want any special doctor? Doctor Dunn has his office just across

the street, you know,” said Georgia.

Three-card deigned to speak.

“I wouldn’t let that crook mend a sick canary for me, leave alone put a

hand on my leg. That leg is bust. I’ll have Doc Wilton or nobody.”

Georgia pulled out of the passing file of the curious a sunburned young

cow-puncher. His nose was toasted raw, which always makes young men

appear cross but honest.

“Sammy, you go and get Doc Wilton like a good fellow,” said Georgia.

The face of Sammy fell at least a block. He was enjoying this battle

site. But Georgia was not a girl to be refused. With a sigh, Sammy

departed for the doctor, and Georgia impressed four more men to carry

Three-card into the little adjoining room, while she gingerly, with a

white face and compressed lips, supported the broken lee. She had him put

on a table, and placed a cushion under his head. She borrowed a whisky

flask from another puncher and gave Three-card a good swig of it. She

wiped the sweat of pain from his face. She unloosed the shirt at his

throat. With unexpected skill, she rolled another cigarette for him and

lighted it.

“You’re a bit of all right,” said Three-card, his bird eyes glittering at

her suddenly in an unwinking stare, like that of a hawk.

“Are you comfortable? More comfortable, I mean.” Three-card closed his

eyes. He did not answer, but began to chuckle softly.

“You wouldn’t ‘a’ believed,” said he. “I guess that he never pulled the

trigger.”

Georgia looked at the smashed window glass at the end of the room.

“You don’t mean the Kid?” she said.

“Don’t I?” snarled Three-card.

Then he seemed to remember that she had been kind.

“Yeah, that’s who I mean,” said he.

She tried to understand, but her mind whirled. With her own eyes she had

seen the results of the explosion which occurred when the Kid had entered

this house. She had seen men hurled out from it through windows and doors

as if dynamite were bursting within.

“What did he use, if not a gun?” she asked.

“He used his bean,” said Three-card.

This answer he seemed to think sufficient, and he nodded in satisfaction.

“Aces will always take tricks,” said Three-card. “He was all full of

aces.”

He chuckled again. He seemed to forget his own predicament.

“He was always in the next room,” said Three-card. “I wasn’t proud. I

went down into the cellar, but the cellar window was too narrow to

squeeze out.”

“Did the Kid follow you down there?” asked the girl.

She tried to make the picture bright in her mind, of the terrified men in

the cellar, and the fear of the Kid upon them.

“All he done was to open the door at the head of the stairs and wait!”

said Three-card, still chuckling in admiration of his enemy’s maneuvers.

“Somebody said that he was gunna throw a can of oil down and a lighted

match after it. Then we charged up those stairs and crushed out through

the doorway—and found that he wasn’t in the upper hall at all! Then we

bolted for the upstairs, because it seemed like the Kid was always just

about gunna step through an open door and start shooting.”

She caught her breath. She understood that nightmare fear which had

possessed all in the house.

“On the way up I heard a sound. I looked back. I was the last of the

hunch going up, and there was the Kid in the hall right at the foot of

the stairs, with his gun ready. I pulled mine and turned to shoot, and

just fell down the stairs and busted my leg. The Kid goes on up. Hell

busts wide open all over the house. Pretty soon there’s quiet. Down comes

somebody walking, whistling. It’s the Kid. He stops and makes me a

cigarette.

“‘Hard luck, Three-card,’ says he.”

Three-card paused. He looked into the face of the girl.

“You’d ‘v’ liked to see,” said Three-card.

“Yes,” said Georgia beneath her breath. “I would!”

The Kid had stopped with red-headed Davey Trainor long enough to give him

a ride on the Duck Hawk. Then he brought from one of his pockets a small

knife. It had three blades of the finest steel, which he displayed and

illustrated their uses. Then he mounted.

Davey stood by him, bending back his head and looking up at the picture

of the hero against the blue sky.

“You wouldn’t be comin’ back here one of these days?” he asked.

“Sure I would,” said the Kid. “Don’t you be forgetting me.”

“Me?” said Davey. “Golly, I should say not. So long, Kid.”

“So long,” said the Kid.

Then he took off his hat and waved it toward the window of a neighboring

house, over which honeysuckle vines descended in a thick shower.

“Ma’am,” said he, “you’ve been aiming too low.”

With this he rode off down the street whistling.

Old John Dale saw him go by, with the Duck Hawk cakewalking in time and

rhythm with the whistled tune. They seemed to be

Comments (0)