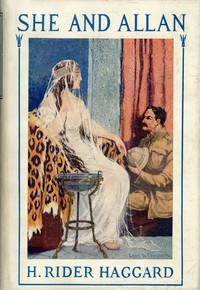

She and Allan, H. Rider Haggard [best summer reads .txt] 📗

- Author: H. Rider Haggard

Book online «She and Allan, H. Rider Haggard [best summer reads .txt] 📗». Author H. Rider Haggard

So off we went, about twenty of the village natives, a motley crew armed with every kind of gun, marching ahead and singing songs. Then came the waggon with Captain Robertson and myself seated on the driving-box, and lastly Umslopogaas and his Zulus, except the two who had been left behind.

We trekked along a kind of native road over fine veld of the same character as that on which Strathmuir stood, having the lower-lying bush-veld which ran down to the Zambesi on our right. Before nightfall we came to a ridge whereon this bush-veld turned south, fringing that tributary of the great river in the swamps of which we were to hunt for sea-cows. Here we camped and next morning, leaving the waggon in charge of my voorlooper and a couple of the Strathmuir natives, for the driver was to act as my gun-bearer—we marched down into the sea of bush-veld. It proved to be full of game, but at this we dared not fire for fearing of disturbing the hippopotami in the swamps beneath, whence in that event they might escape us back to the river.

About midday we passed out of the bush-veld and reached the place where the drive was to be. Here, bordered by steep banks covered with bush, was swampy ground not more than two hundred yards wide, down the centre of which ran a narrow channel of rather deep water, draining a vast expanse of morass above. It was up this channel that the sea-cows travelled to the feeding ground where they loved to collect at that season of the year.

There with the assistance of some of the riverside natives we made our preparations under the direction of Captain Robertson. The rest of these men, to the number of several hundreds, had made a wide détour to the head of the swamps, miles away, whence they were to advance at a certain signal. These preparations were simple. A quantity of thorn trees were cut down and by means of heavy stones fastened to their trunks, anchored in the narrow channel of deep water. To their tops, which floated on the placid surface, were tied a variety of rags which we had brought with us, such as old red flannel shirts, gay-coloured but worn-out blankets, and I know not what besides. Some of these fragments also were attached to the anchored ropes under water.

Also we selected places for the guns upon the steep banks that I have mentioned, between which this channel ran. Foreseeing what would happen, I chose one for myself behind a particularly stout rock and what is more, built a stone wall to the height of several feet on the landward side of it, as I guessed that the natives posted near to me would prove wild in their shooting.

These labours occupied the rest of that day, and at night we retired to higher ground to sleep. Before dawn on the following morning we returned and took up our stations, some on one side of the channel and some on the other which we had to reach in a canoe brought for the purpose by the river natives.

Then, before the sun rose, Captain Robertson fired a huge pile of dried reeds and bushes, which was to give the signal to the river natives far away to begin their beat. This done, we sat down and waited, after making sure that every gun had plenty of ammunition ready.

As the dawn broke, by climbing a tree near my schanze or shelter, I saw a good many miles away to the south a wide circle of little fires, and guessed that the natives were beginning to burn the dry reeds of the swamp. Presently these fires drew together into a thin wall of flame. Then I knew that it was time to return to the schanze and prepare. It was full daylight, however, before anything happened.

Watching the still channel of water, I saw ripples on it and bubbles of air rising. Suddenly there appeared the head of a great bull-hippopotamus which, having caught sight of our rag barricade, either above or below water, had risen to the surface to see what it might be. I put a bullet from an eight-bore rifle through its brain, whereon it sank, as I guessed, stone dead to the bottom of the channel, thus helping to increase the barricade by the bulk of its great body. Also it had another effect. I have observed that sea-cows cannot bear the smell and taint of blood, which frightens them horribly, so that they will expose themselves to almost any risk, rather than get it into their nostrils.

Now, in this still water where there was no perceptible current, the blood from the dead bull soon spread all about so that when the herd, following their leader, began to arrive they were much alarmed. Indeed, the first of them on winding or tasting it, turned and tried to get back up the channel where, however, they met others following, and there ensued a tremendous confusion. They rose to the surface, blowing, snorting, bellowing and scrambling over each other in the water, while continually more and more arrived behind them, till there was a perfect pandemonium in that narrow place.

All our guns opened fire wildly upon the mass; it was like a battle and through the smoke I caught sight of the riverside natives who were acting as beaters, advancing far away, fantastically dressed, screaming with excitement and waving spears, or sometimes torches of flaming reeds. Most of these were scrambling along the banks, but some of the bolder spirits advanced over the lagoon in canoes, driving the hippopotami towards the mouth of the channel by which alone they could escape into the great swamps below and so on to the river. In all my hunting experience I do not think I ever saw a more remarkable scene. Still, in a way, to me it was unpleasant, for I flatter myself that I am a sportsman and a battle of this sort is not sport as I understand the term.

At length it came to this; the channel for quite a long way was literally full of hippopotami—I should think there must have been a hundred of them or more of all sorts and sizes, from great bulls down to little calves. Some of these were killed, not many, for the shooting of our gallant company was execrable and almost at hazard. Also for every sea-cow that died, of which number I think that Captain Robertson and myself accounted for most—many were only wounded.

Still, the unhappy beasts, crazed with noise and fire and blood, did not seem to dare to face our frail barricade, probably for the reason that I have given. For a while they remained massed together in the water, or under it, making a most horrible noise. Then of a sudden they seemed to take a resolution. A few of them broke back towards the burning reeds, the screaming beaters and the advancing canoes. One of these, indeed, a wounded bull, charged a canoe, crushed it in its huge jaws and killed the rower, how exactly I do not know, for his body was never found. The majority of them, however, took another counsel, for emerging from the water on either side, they began to scramble towards us along the steep banks, or even to climb up them with surprising agility. It was at this point in the proceedings that I congratulated myself earnestly upon the solid character of the water-worn rock which I had selected as a shelter.

Behind this rock together with my gun-bearer and Umslopogaas, who, as he did not shoot, had elected to be my companion, I crouched and banged away at the unwieldy creatures as they advanced. But fire fast as I might with two rifles, I could not stop the half of them—they were drawing unpleasantly near. I glanced at Umslopogaas and even then was amused to see that probably for the first time in his life that redoubtable warrior was in a genuine fright.

“This is madness, Macumazahn,” he shouted above the din. “Are we to stop here and be stamped flat by a horde of water-pigs?”

“It seems so,” I answered, “unless you prefer to be stamped flat outside—or eaten,” I added, pointing to a great crocodile that had also emerged from the channel and was coming along towards us with open jaws.

“By the Axe!” shouted Umslopogaas again, “I—a warrior—will not die thus, trodden on like a slug by an ox.”

Now I have mentioned a tree which I climbed. In his extremity Umslopogaas rushed for that tree and went up it like a lamplighter, just as the crocodile wriggled past its trunk, snapping at his retreating legs.

After this I took no more note of him, partly because of the advancing sea-cows, and more for the reason that one of the village natives posted above me, firing wildly, put a large round bullet through the sleeve of my coat. Indeed, had it not been for the wall which I built that protected us, I am certain that both my bearer and I would have been killed, for afterwards I found it splashed over with lead from bullets which had struck the stones.

Well, thanks to the strength of my rock and to the wall, or as Hans said afterwards, to Zikali’s Great Medicine, we escaped unhurt. The rush went by me; indeed, I killed one sea-cow so close that the powder from the rifle actually burned its hide. But it did go by, leaving us untouched. All, however, were not so fortunate, since of the village natives two were trampled to death, while a third had his leg broken.

Also, and this was really amusing—a bewildered bull charging at full speed, crashed into the trunk of Umslopogaas’ tree, and as it was not very thick, snapped it in two. Down came the top in which the dignified chief was ensconced like a bird in a nest, though at that moment there was precious little dignity about him. However, except for scratches he was not hurt, as the hippopotamus had other business in urgent need of attention and did not stop to settle with him.

“Such are the things which happen to a man who mixes himself up with matters of which he knows nothing,” said Umslopogaas sententiously to me afterwards. But all the same he could never bear any allusion to this tree-climbing episode in his martial career, which, as it happened, had taken place in full view of his retainers, among whom it remained the greatest of jokes. Indeed, he wanted to kill a man, the wag of the party, who gave him a slang name which, being translated, means “He-who-is-so-brave-that-he-dares-to-ride-a-water-horse-up-a-tree. ”

It was all over at last, for which I thanked Providence devoutly. A good many of the sea-cows were dead, I think twenty-one was our exact bag, but the majority of them had escaped in one way or another, many as I fear, wounded. I imagine that at the last the bulk of the herd overcame its fears and swimming through our screen, passed away down the channel. At any rate they were gone, and having ascertained that there was nothing to be done for the man who had been trampled on my side of the channel, I crossed it in the canoe with the object of returning quietly to our camp to rest.

But as yet there was to be no quiet for me, for there I found Captain Robertson, who I think had been refreshing himself out of a bottle and was in a great state of excitement about a native who had been killed near him who was a favourite of his, and another whose leg was broken. He declared vehemently that the hippopotamus which had done this had been wounded and rushed into some bushes a few hundred yards away, and that he meant to take vengeance upon it. Indeed, he was just setting off to do so.

Seeing his agitated state I thought it wisest to follow him. What happened need not be set out in detail. It is sufficient to say that he found that hippopotamus and blazed both barrels at it in the bushes, hitting it, but not seriously. Out lumbered the creature with its mouth open, wishing to escape. Robertson turned to fly as he was in its path, but from one cause or another, tripped and fell down. Certainly he would have been crushed beneath its huge feet had I not stepped in front of him and sent two solid eight-bore bullets down that yawning throat, killing it dead within three feet of where Robertson was trying to rise, and I may add, of myself.

This narrow escape sobered him, and I am bound to say that his gratitude was profuse.

“You are a brave man,” he

Comments (0)