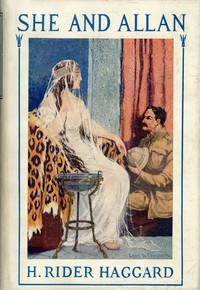

She and Allan, H. Rider Haggard [best summer reads .txt] 📗

- Author: H. Rider Haggard

Book online «She and Allan, H. Rider Haggard [best summer reads .txt] 📗». Author H. Rider Haggard

“Hans,” I said, “you have been drinking and because of it the lady Sad-Eyes is taken a prisoner by cannibals; for had you been awake and watching, you might have seen them coming and saved her and the rest. Still, afterwards you did well, and for the rest you must answer to Heaven.”

“I must tell your reverend father, the Predikant, Baas, that the white master, Red-Beard, gave me the liquor and it is rude not to do as a great white master does, and drink it up. I am sure he will understand, Baas,” said Hans abjectly.

I thought to myself that it was true and that the spear which Robertson cast had fallen upon his own head, as the Zulus say, but I made no answer, lacking time for argument.

“Did you say,” asked Umslopogaas, speaking for the first time, “that my servants killed only six of these men-eaters?”

Hans nodded and answered, “Yes, six. I counted the bodies.”

“It was ill done, they should have killed six each,” said Umslopogaas moodily. “Well, they have left the more for us to finish,” and he fingered the great axe.

Just then Captain Robertson arrived in his waggon, calling out anxiously to know what was the matter, for some premonition of evil seemed to have struck him. My heart sank at the sight of him, for how was I to tell such a story to the father of the murdered children and of the abducted girl?

In the end I felt that I could not. Yes, I turned coward and saying that I must fetch something out of the waggon, bolted into it, bidding Hans go forward and repeat his tale. He obeyed unwillingly enough and looking out between the curtains of the waggon tent I saw all that happened, though I could not hear the words that passed.

Robertson had halted the oxen and jumping from the waggon-box strode forward and met Hans, who began to speak with him, twitching his hat in his hands. Gradually as the tale progressed, I saw the Captain’s face freeze into a mask of horror. Then he began to argue and deny, then to weep—oh! it was a terrible sight to see that great man weeping over those whom he had lost, and in such a fashion.

After this a kind of blind rage seized him and I thought he was going to kill Hans, who was of the same opinion, for he ran away. Next he staggered about, shaking his fists, cursing and shouting, till presently he fell of a heap and lay face downwards, beating his head against the ground and groaning.

Now I went to him because I must.

He saw me coming and sat up.

“That’s a pretty story, Quatermain, which this little yellow monkey has been gibbering at me. Man, do you understand what he says? He says that all those half-blood children of mine are dead, murdered by savages from over the Zambesi, yes, and eaten, too, with their mothers. Do you take the point? Eaten like lambs. Those fires your man saw last night were the fires on which they were cooked, my little so-and-so and so-and-so,” and he mentioned half a dozen different names. “Yes, cooked, Quatermain. And that isn’t all of it, they have taken Inez too. They didn’t eat her, but they have dragged her off a captive for God knows what reason. I couldn’t understand. The whole ship’s crew is gone, except the captain absent on leave and the first officer, Thomaso, who deserted with some Lascar stokers, and left the women and children to their fate. My God, I’m going mad. I’m going mad! If you have any mercy in you, give me something to drink.”

“All right,” I said, “I will. Sit here and wait a minute.”

Then I went to the waggon and poured out a stiff tot of spirits into which I put an amazing dose of bromide from a little medicine chest I always carry with me, and thirty drops of chlorodyne on the top of it. All this compound I mixed up with a little water and took it to him in a tin cup so that he could not see the colour.

He drank it at a gulp and throwing the pannikin aside, sat down on the veld, groaning while the company watched him at a respectful distance, for Hans had joined the others and his tale had spread like fire in drought-parched grass.

In a few minutes the drugs began to take effect upon Robertson’s tortured nerves, for he rose and said quietly,

“What now?”

“Vengeance, or rather justice,” I answered.

“Yes,” he exclaimed, “vengeance. I swear that I will be avenged, or die—or both.”

Again I saw my opportunity and said, “You must swear more than that, Robertson. Only sober men can accomplish great things, for drink destroys the judgment. If you wish to be avenged for the dead and to rescue the living, you must be sober, or I for one will not help you.”

“Will you help me if I do, to the end, good or ill, Quatermain?” he added.

I nodded.

“That’s as much as another’s oath,” he muttered. “Still, I will put my thought in words. I swear by God, by my mother—like these natives—and by my daughter born in honest marriage, that I will never touch another drop of strong drink, until I have avenged those poor women and their little children, and rescued Inez from their murderers. If I do you may put a bullet through me.”

“That’s all right,” I said in an offhand fashion, though inwardly I glowed with pride at the success of my great idea, for at the time I thought it great, and went on,

“Now let us get to business. The first thing to do is to trek to Strathmuir and make preparations; the next to start upon the trail. Come to sit on the waggon with me and tell me what guns and ammunition you have got, for according to Hans those savages don’t seem to have touched anything, except a few blankets and a herd of goats.”

He did as I asked, telling me all he could remember. Then he said,

“It is a strange thing, but now I recall that about two years ago a great savage with a high nose, who talked a sort of Arabic which, like Inez, I understand, having lived on the coast, turned up one day and said he wanted to trade. I asked him what in, and he answered that he would like to buy some children. I told him that I was not a slave-dealer. Then he looked at Inez, who was moving about, and said that he would like to buy her to be a wife for his Chief, and offered some fabulous sum in ivory and in gold, which he said should be paid before she was taken away. I snatched his big spear from his hand, broke it over his head and gave him the best hiding with its shaft that he had ever heard of. Then I kicked him off the place. He limped away but when he was out of reach, turned and called out that one day he would come again with others and take her, meaning Inez, without leaving the price in ivory and gold. I ran for my gun, but when I got back he had gone and I never thought of the matter again from that day to this.”

“Well, he kept his promise,” I said, but Robertson made no answer, for by this time that thundering dose of bromide and laudanum had taken effect on him and he had fallen asleep, of which I was glad, for I thought that this sleep would save his sanity, as I believe it did for a while.

We reached Strathmuir towards sunset, too late to think of attempting the pursuit that day. Indeed, during our trek, I had thought the matter out carefully and come to the conclusion that to try to do so would be useless. We must rest and make preparations; also there was no hope of our overtaking these brutes who already had a clear twelve hours’ start, by a sudden spurt. They must be run down patiently by following their spoor, if indeed they could be run down at all before they vanished into the vast recesses of unknown Africa. The most we could do this night was to get ready.

Captain Robertson was still sleeping when we passed the village and of this I was heartily glad, since the remains of a cannibal feast are not pleasant to behold, especially when they are——! Indeed, of these I determined to be rid at once, so slipping off the waggon with Hans and some of the farm boys, for none of the Zulus would defile themselves by touching such human remnants—I made up two of the smouldering fires, the light of which the voorlooper had seen upon the sky, and on to them cast, or caused to be cast, those poor fragments. Also I told the farm natives to dig a big grave and in it to place the other bodies and generally to remove the traces of murder.

Then I went on to the house, and not too soon. Seeing the waggons arrive and having made sure that the Amahagger were gone, Thomaso and the other cowards emerged from their hiding-places and returned. Unfortunately for the former the first person he met was Umslopogaas, who began to revile the fat half-breed in no measured terms, calling him dog, coward, and other opprobrious names, such as deserter of women and children, and so forth—all of which someone translated.

Thomaso, an insolent person, tried to swagger the matter out, saying that he had gone to get assistance. Infuriated at this lie, Umslopogaas leapt upon him with a roar and though he was a strong man, dealt with him as a lion does with a buck. Lifting him from his feet, he hurled him to the ground, then as he strove to rise and run, caught him again and as it seemed to me, was about to break his back across his knee. Just at this juncture I arrived.

“Let the man go,” I shouted to him. “Is there not enough death here already?”

“Yes,” answered Umslopogaas, “I think there is. Best that this jackal should live to eat his own shame,” and he cast Thomaso to the ground, where he lay groaning.

Robertson, who was still asleep in the waggon, woke up at the noise, and descended from it, looking dazed. I got him to the house and in doing so made my way past, or rather between the bodies of the two Zulus and of the six men whom they had killed, also of him whom Inez had shot. Those Zulus had made a splendid fight for they were covered with wounds, all of them in front, as I found upon examination.

Having made Robertson lie down upon his bed, I took a good look at the slain Amahagger. They were magnificent men, all of them; tall, spare and shapely with very clear-cut features and rather frizzled hair. From these characteristics, as well as the lightness of their colour, I concluded that they were of a Semitic or Arab type, and that the admixture of their blood with that of the Bantus was but slight, if indeed there were any at all. Their spears, of which one had been cut through by a blow of a Zulu’s axe, were long and broad, not unlike to those used by the Masai, but of finer workmanship.

By this time the sun was setting and thoroughly tired by all that I had gone through, I went into the house to get something to eat, having told Hans to find food and prepare a meal. As I sat down Robertson joined me and I made him also eat. His first impulse was to go to the cupboard and fetch the spirit bottle; indeed, he rose to do so.

“Hans is making coffee,” I said warningly.

“Thank you,” he answered, “I forgot. Force of habit, you know.”

Here I may state that never from that moment did I see him touch another drop of liquor, not even when I drank my modest tot in front of him. His triumph over temptation was

Comments (0)