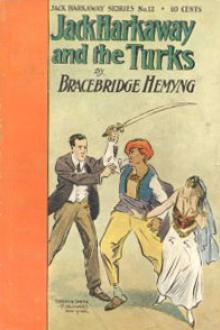

Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks, Bracebridge Hemyng [the two towers ebook TXT] 📗

- Author: Bracebridge Hemyng

- Performer: -

Book online «Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks, Bracebridge Hemyng [the two towers ebook TXT] 📗». Author Bracebridge Hemyng

"Down with the wretch!"

"Tear him to pieces!"

"Let him be impaled!" cried the multitude.

With these dire threats, the angry crowd rushed towards Mr. Figgins, headed by a short, fat Turk, who was particularly indignant.

The luckless orphan, anxious to avoid the terrible doom that was threatening him, rushed away in an opposite direction.

The Turks are not, as a rule, remarkable for swift running.

Mr. Figgins, whose pace was quickened by the dreadful prospect of a stake through his body, would have easily distanced them.

But unfortunately, his green and yellow striped turban, dislodged from its position, fell—as his hat had previously done—over his eyes, and almost smothered him.

He tugged away at it as he ran, in order to get rid of it.

But all he succeeded in doing was to loosen one of the ends.

Gradually the turban began to unwind itself, the end trailing on the ground.

The Turk in pursuit caught up this end, and grasping it firmly, brought all his weight to bear upon the fugitive.

Suddenly the hapless Figgins began to feel strong symptoms of strangulation.

The next moment, a sharp jerk from the burly Turk pulled him to the ground.

But this saved him.

No sooner was he prostrate on his back than the turban slipped from his head, and he was free.

Springing to his feet, he darted off at a speed which no human grocer could ever have dreamt of.

He was soon far beyond pursuit.

All he had lost was his green and yellow striped turban.

But the loss of that, though it somewhat fretted him, had saved his life.

He found himself in a retired spot, and no one being near, he sat down to reflect and recover his breath.

"What a country this is," he thought; "pleasant enough, though, as far as the climate goes; but the people in it are awful! What a lot of bloodthirsty, bilious-looking wretches, to be sure; ready to consign to torture and death a poor innocent, unprotected orphan because he happens to be of a different colour from themselves!"

So perturbed were the thoughts of Mr. Figgins that he was obliged to smoke a cigar to soothe himself.

But even this failed to quiet his agitated nerves.

His mind was full of gloomy apprehensions.

"Where am I?" he asked himself. "How am I to get home? I shall be sure to meet some of the rabble, and with them and the dogs I shall be torn to pieces. What will become of me—wretched orphan that I am! What shall I do?"

Hardly had he uttered these distressful exclamations when a prolonged note of melody caught his ear.

"Hark!" he said to himself, "there is music. 'Music hath charms to soothe the savage breast,' says the poet, and it seems to have a soothing effect upon my nerves."

The strain had died away, and was heard no longer.

Mark Antony Figgins was in despair.

"Play again, sweet instrument," he cried, anxiously, "play again."

Again the sweet note sounded and again the solitary orphan felt comforted.

"It's a flute; it must be a flute," he murmured to himself, as he listened. "I always liked the flute. It's so soft and melancholy."

The grocer had a faint recollection of his boyhood's days, when he had been a tolerably efficient performer on a penny whistle.

Just at this moment the mournful note he heard recalled the past vividly.

So vividly, that Mr. Figgins, in the depths of his loneliness, fixed his eyes sadly on the turned-up toes of his leather slippers, and wept.

As the melody proceeded, so did the drops pour more copiously from the orphan's eyes.

And no wonder, for of all the doleful too-tooings ever uttered by wind instrument, this was the dolefullest.

But it suited Mr. Figgin's mood at that moment.

"It's a Turkish flute, I suppose," he sobbed; "but it's very beau-u-u-tiful. I wish I had a flute."

He got up and looked round, and found himself outside an enclosure of thick trees.

It was evidently within this enclosure the flute player was located.

As the reader knows, there was nothing bold or daring about Mark Antony Figgins.

But now the flute seemed to have inspired him with a kind of supernatural recklessness.

"I'd give almost any thing for that flute," he murmured to himself. "I feel that I should like to play the flute. I wonder who it is playing it, and whether he'd sell it?"

The unseen performer, at this juncture, burst forth into such a powerfully shrill cadence that the orphan was quite thrilled with delight.

"A railway whistle's a fool to it!" he cried, as he clapped his hands in ecstasy. "Bravo, bravo! Encore!"

Having shouted his applause till he was hoarse, he walked along by the side of the wall, seeking anxiously for some place of entrance.

At length he came to an open gate.

A stout gentleman—unmistakably a Turk—with a crimson cap on his head, ornamented with a tassel, and a long, reed-like instrument in his hand, was looking cautiously forth.

It was evidently the musician, who, having been interrupted in his solo, had come to see who the delinquent was that had disturbed him.

The enthusiastic Figgins had caught sight of the flute, and that was sufficient.

Forgetting his usual nervous timidity, he rushed forward.

"My dear sir," he exclaimed, "it was exquisite—delicious! Pray oblige me with another tune—or, if you have no objection, let me attempt one."

As he spoke, the excited Figgins stretched forth both his hands.

The owner of the flute, who evidently suspected an attempt at robbery, quietly placed his instrument behind him, and looking hard at Figgins, said sternly—

"What son of a dog art thou?"

To which Figgins replied mildly—

"You're mistaken, my dear sir; I'm the son of my father and mother, but they—alas!—are no more, and I am now only a poor desolate orphan."

The tears trickled from his eyes as he spoke.

The Turk did not appear in the least affected.

"What bosh is all this?" he asked, after a moment, in a hard, unsympathetic tone.

"It's no bosh at all, I assure you, my dear signor," replied Figgins, earnestly; "the fact is, I heard you play on your flute, and its sweet tones so soothed my spirits—which are at this moment extremely low—that I am come to make several requests."

"Umph!" growled the Turk; "what are they?"

"First, that you will play me another of your charming airs, next, that you will allow me to attempt one myself, and thirdly, that you will sell me the instrument you hold in your hand.'"

The Turk glared for a moment fiercely at the proposer of these modest requests, and then politely wishing the graves of his departed relatives might be perpetually defiled, he replied curtly—

"First, I am not going to play any more to-night; next, I will see you in Jehanum[1] before I allow you to play; and thirdly, I won't sell my flute."

[1] The abode of lost spirits.

With these words, he stepped back into the garden and slammed the gate in Mr. Figgins' face.

"I shall never get over this," Figgins murmured to himself, gloomily; "that flute would have cheered my solitary hours, and that ruthless Turk refuses to part with it. Now, indeed, I feel my peace of mind is gone forever."

His grief at this juncture became so overpowering, that he leant against the door, and in his despair hammered it with his head.

Suddenly the door burst open, and the distressed orphan, in all his brilliant array, shot backwards into some shrubs of a prickly nature, whose sharp thorns added to his agonizing sensations.

"Will anybody be kind enough to put an end to my misery?" he wailed, as he lay on his back, feeling as though he had been transformed into a human pincushion.

He was not a little surprised to hear a familiar voice exclaim—

"Lor' bless me! dat you, Massa Figgins?"

Glancing up, he espied the black face of Bogey looking down upon him.

"Yes, it's me," he answered, in a wailing tone; "help me up."

"Gib me you fist," cried Bogey.

Mr. Figgins extended his hand, and the negro grasping it, by a vigorous jerk hoisted the prostrate grocer out of his thorny bed, tingling all over as though he had been stung by nettles.

Bogey was quite astounded at the transformation of his dress.

"Why, Massa Figgins, what out-and-out guy you look!" he exclaimed; "whar all you hair gone to?"

The orphan only groaned.

He was thinking of another h-air (without the h), the air he had heard on the Turkish flute.

Just at that moment the too-too-too of the instrument sounded again.

Figgins stood like one absorbed.

All his agonizing pains were at once forgotten.

"How sweet, how plaintive!" he murmured to himself; "too-too-too, tooty-tooty-too!" he hummed, in imitation of the sound.

Bogey heard it also, and involuntarily put his hands on big stomach and made a comically wry face.

"Whar dat orful squeakin' row?" he asked.

"Hush, hush!" exclaimed the orphan, holding up his hands reprovingly, and turning up his eyes at the same time; "it's heavenly music; it's a flute, my boyhood's favourite instrument."

"Gorra!" muttered Bogey; "it 'nuff to gib a fellar de mullingrubs all down him back and up him belly."

He looked towards Mr. Figgins, and seeing him standing with his hands clasped looking like a white-washed Turk in a trance, he said—

"What de matter wid yer, Massa Figgins? Am you ill?"

"That flute, that melodious flute, that breathes forth dulcet notes of peace," murmured the orphan, in a deep, absorbed whisper. "I must have that flute."

Bogey felt a little anxious.

"Me t'ink Massa Figgins getting lilly soft in him nut; him losing him hair turn him mad," he said to himself.

"I must have that flute," repeated the grocer, in the same abstracted tone and manner. "I should think it cheap at ten pounds."

Bogey, on hearing this, opened his eyes very wide.

He thought he saw a chance of doing a profitable bit of business on his own account.

So, after an instant, he said quietly—

"Good flute worth more dan ten pounds; rale good blower like dat worth twenty at de bery least."

"Yes, yes; I'd give twenty willingly," murmured the wrapt Figgins.

"Bery good," said Bogey, as he instantly disappeared through the gate.

The orphan remained waiting without.

The "too-too-tooing" was going on in the usual doleful and melancholy manner, and guided by the sound, Bogey crept forward till he came in sight of the performer, who was seated in a snug nook in his garden playing away to his heart's content; or, as the negro supposed, endeavouring to frighten away the birds.

Bogey took stock of the stout player and his flute.

Creeping along the shrubbery till he had got exactly opposite to the flautist, he, in the midst of the too-too-tooing, uttered an unearthly groan.

"Inshallah!" exclaimed the Turk, stopping suddenly; "what was that?"

"It war me," groaned the hidden Bogey more deeply than before.

"Who are you?" faltered the musician, hearing the mysterious voice, but seeing no one.

"Me am special messenger from de Prophet," Bogey replied.

"Allah Kerim! my dream is coming true. Is it the Prophet speaks?" gasped the Turk, his olive cheeks turning the hue of saffron.

"Iss, it de profit brings me here," returned Bogey, truthfully.

"What message does he send to his slave?" asked the old Turk.

"He say you make sich orful row wid dat flute he can git no sleep, an', derefore, he send me to stop it. You got to gib up de flute direckly."

The teeth of the half-silly musician were chattering in his head.

His optics rolled wildly from side to side.

Just at this crisis Bogey, with his eyes glaring and his white teeth fully exposed, thrust his black face from the foliage.

"Drop it," he cried, with a hideous grin.

He had no occasion to repeat the command.

With a yell of terror the horrified Turkish gentleman, who was really half an idiot, and was just then away from his keepers, let fall his instrument from his trembling fingers, and starting up, waddled away from the spot as though the furies were after him, while the special messenger of the Prophet quietly picked up the flute with a chuckle, and retraced his steps to the gate.

Here he found Mr. Figgins.

He could scarcely believe his eyes when he saw the negro with the precious instrument in his hand.

"The flute, the flute!" he cried, "the soother of sorrow,

Comments (0)