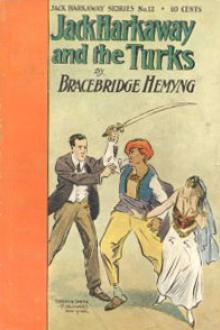

Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks, Bracebridge Hemyng [the two towers ebook TXT] 📗

- Author: Bracebridge Hemyng

- Performer: -

Book online «Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks, Bracebridge Hemyng [the two towers ebook TXT] 📗». Author Bracebridge Hemyng

"Your flute, vile dog, or your life," shouted the Turk.

"I object to part with either," cried the orphan. "Go and have your tooth out, and be happy."

Down came the scimitar with a swish in the direction of his head.

But the grocer had quickly withdrawn it beneath the clothes.

Not to be thwarted, however, in his vengeance, the burly Bosja swooped down upon the heap, and dragged them up in his grasp, the orphan included.

"Now I have you," he cried, as he seized the obnoxious flute.

"Give me my instrument, infidel," shrieked the orphan, as he threw off the blanket, and clung to the flute with desperation.

At the same moment, he recognised the green and yellow-striped turban on the head of the Turk.

It was Bosja into whose hands it had fallen, when Mr. Figgins was escaping from the mob.

"That is my turban," he cried, as with one hand he dragged it from his enemy's head, with dauntless vehemence, and bringing his flute down with a smart crack on the Turk's bald pate.

The Turk, who was much more of a bully than a hero, was quite confounded at the excited energy which the Frankish lodger displayed. Dropping his scimitar, he then had a struggle for the flute.

Round the room they went, pulling and hauling.

At length, lurching against the door, it burst open.

The combatants now found themselves on the landing.

Here the struggle continued, till, at length, giving a desperate tug, the flute came in half, and Bosja fell backwards, head over heels, down the stairs, with the upper joint of the instrument in his hand.

The landlady, who thought the house was falling, came hurrying to see what had happened, and found the Turk lying in a heap at the bottom of the stairs, with the breath almost knocked out of his body.

It took some time to bring him to himself.

It was just as he was recovering there was a loud knocking at the street door.

On opening it, a body of Turkish soldiers appeared drawn up in front of it.

"What is the cause of this disturbance?" inquired the leader of the troop.

Bosja quickly gave his own version of what had happened.

Of course, it was highly exaggerated.

He, a true believer, had been assaulted, robbed of his turban, and thrown downstairs by a rascally dog of a Giaour, who lodged in a room next to him.

This was quite sufficient to arouse the indignation of the officer, and, with three of his troop, that functionary ascended to seize the delinquent.

But, on reaching the room, it was discovered to be empty.

"The Frankish hound laughs at our beards," said the officer. "He has escaped by the window."

And such had been the intention of Mark Antony Figgins.

But not being accustomed to such perilous descents, he had found himself baffled in his flight, and was now perched on a ledge, half way between the window and the ground, unable either to proceed or to return.

He was soon espied by the soldiers, and a shout announced his detection.

A ladder was quickly procured, and the luckless orphan very shortly found himself a prisoner.

"What dirt have you been eating?" demanded the officer, sternly.

"I haven't been eating dirt at all," returned the indignant Figgins, "but I believe that fat Turk has swallowed half of my flute."

Bosja came forward at this with the missing portion in his hand, and handed it to the officer.

The orphan made a snatch at it, but received only a box on the ear from the officer.

The other half of his cherished instrument was wrested from him, and he marched off to the lock-up until the case could be tried on the morrow before the bashaw.

CHAPTER LXVI.

HOW THE FLUTE ADVENTURE TERMINATED.

The morrow had come.

Hearing that a Frank was to be tried, the court was crowded.

At the appointed hour Mark Antony Figgins, looking particularly doleful, was conducted from his cell to the presence of the administrator of the law.

Osman, the ruling bashaw, although a Turk, was a regular Tartar to deal with.

He administered plenty of law, but very little justice; if the latter was required, money was the bashaw's idol, and it must be handsomely paid for.

As soon as the parties were brought in, the judicial potentate eyed them sternly for some time.

Then he said—

"Which is the plaintiff?"

"I am," exclaimed Bosja.

"No; I am," exclaimed Mr. Figgins.

"What bosh is this?" cried the bashaw; "you can't both be plaintiffs."

"Most high and mighty, he robbed me of my turban and knocked me down stairs," affirmed Bosja.

"No, your worship; he robbed me of my turban and stole half my flute," protested the orphan.

The official dignitary frowned and shut his eyes reflectively.

He foresaw that he had a case of unusual intricacy before him, and he was thinking how he should deal with it.

After a moment he opened his eyes, rubbed his nose profoundly, and sneezed.

All the officials imitated their superior by rubbing their noses and sneezing in concert.

The uproar was tremendous.

Order being at length restored, the bashaw fixed his eyes upon Bosja, and said to him—

"Let me hear what you have to say."

"It is this. Your slave last night was troubled with the toothache, and retired to his couch. The pain kept me awake, and just as I was going to sleep—"

"Stop!" cried the bashaw; "you say that the pain kept you awake, and then you say you were going to sleep. You couldn't be awake and asleep at the same time."

A hum of applause ran round the court at this sagacious remark.

"He speaks the words of wisdom," murmured some.

"What a lawyer he is," whispered others.

"I had been awake for some hours," explained Bosja, "when the pain lulled a little, and I began to doze."

"Well, you began to doze, and then?"

"Then I was disturbed by a dreadful squeaking noise in the next room."

"A rat?"

"No, your highness; a flute."

"That was my flute, your worship," cried the indignant orphan; "whose dulcet tone he calls a dreadful sque——"

"Silence, dog," shouted the bashaw.

"Silence," shouted everyone else.

"Continue," said the judge to Bosja.

"I endured the dreadful sound as long as I could, until the anguish of my tooth became so great I could bear it no longer, and I sent a civil messenger to the Frank yonder to cease."

"And he complied with your request?"

"Not he, your mightiness. He played all the louder, and the dreadful noise he made nearly killed me."

"I was in my own room, your worship," interposed Mr. Figgins, "and had a right to play as loud as I liked."

The bashaw here referred to his vizier.

"What says the law?" he asked, in a low tone. "Does it permit a man to do what he likes in his own room?"

The vizier scratched his nose and reflected.

All the officials scratched their noses and reflected.

After a moment the vizier replied—

"It all depends, most wise and illustrious. If the owner of the room be a true believer, he may turn it upside down if he please, not else."

"Good; and this flute-player is an infidel—a dog."

"I beg your pardon, sir, I'm a retired grocer," put in Figgins, who overheard the remark.

"Silence," growled the bashaw; "go on, plaintiff."

"Well, your highness," continued Bosja, "I continued to get worse and worse under this dreadful 'too-tooting', until at last, driven to desperation, I sprang from my bed, and hammered at the wall, imploring him to be quiet."

"And he still refused?"

"He did, your mightiness."

"And you?"

"I was imploring Allah to soften his unmerciful heart, when suddenly he burst through the partition, which was thin——"

"No, no, no, your worship," interrupted Mr. Figgins, vehemently, "it was he who burst through, not me."

"Silence," cried the bashaw; "dare not to interrupt the words of truth."

"But they're not words of truth, your worship; they're abominable—false."

"Silence, dog," shouted the potentate, crimson with anger.

"Silence, dog," echoed the rest of the judicial body.

"Continue, plaintiff."

"Well, your highness," went on Bosja, "he then seized me violently, tore my turban from my head, and endeavoured to thrust his diabolical, 'too-tooing' instrument down my throat."

"To which you objected?"

"Strongly, your highness. I seized the flute in self-defence, and it came in half in my hand, and he then dragged me from the room, and with gigantic strength, hurled me backwards down the stairs."

"Allah Kerin, it was a mercy your back was not broken," exclaimed the bashaw.

"I feel sore all over, your highness," said Bosja, ruefully, "and fear I am seriously injured."

"And the culprit was endeavouring to escape, was he not?" asked the judge.

"He was, your mightiness, when my soldiers discovered him clinging to the wall," replied the officer of the soldiers.

"Wallah thaih, it is well said."

The bashaw conferred again with his vizier for a moment, and then, turning towards the luckless Figgins, who found himself changed from the plaintiff into the defendant, he said to him sternly—

"And now, unbelieving dog, what have you to say?"

"Only this," the orphan replied, without hesitation; "that that witness has uttered a tissue of abominable lies."

"I have spoken naught but the truth," exclaimed the unblushing Bosja, solemnly. "Bashem ustun, upon my head be it."

"Well, let us hear what account you have to give," said the bashaw to the defendant.

"My account is very simple," said Figgins. "I was playing my flute, when that Turk insisted on my stopping. I considered I had a right to do as I liked in my own apartment and refused."

"You had no right to do as you liked."

"What, not in my own chamber that I had paid for?"

"Certainly not."

Mr. Figgins shook his clenched fist fiercely in the air at this extraordinary declaration.

"There's neither law nor justice here," he cried, indignantly. "In England——"

"You're not in England, dog," shouted the bashaw, "you're in Turkey."

The orphan felt painfully at that moment that he was.

"I don't care how soon I'm out of such a miserable den of thieves and rogues," he said.

"What does the fellow say?" demanded the bashaw, who did not quite understand all the orphan said.

"He says his face will be whitened by the rays of your highness's wisdom, the like to which he has never before seen," the vizier interpreted.

"Umph!" growled his superior.

Then addressing himself once more to the defendant, he said—

"Go on."

"Well, in the midst of my practice that fat Turk burst through the partition of my room, scimitar in hand. The first thing I saw on his head was my turban, which I lost a week ago. I seized my own property——"

"Inshallah!" shouted the bashaw, "this fellow is telling the same story as the other. He is laughing at our beards and making us eat dirt. I'll hear no more."

"But, your worship——"

"I'll hear no more!" shouted the judge. "I find him guilty on all points."

"But my flute——"

"Your flute is forfeited."

The orphan uttered a cry of despair.

"My flute that cost me twenty-five pounds only a week since," he wailed dolefully.

The bashaw pricked up his ears at these words.

A man who could afford to give twenty-five pounds for a flute must be possessed of property.

The scales of justice quivered whilst he whispered to his vizier—

"This Frank is rich, is he not?"

"Heaven forbid that I should venture to dispute your highness's opinion. Most of his countrymen are so," the subordinate replied.

"Let us see."

Looking towards the agitated grocer, the bashaw said, in a modified tone—

"The law pronounces you guilty. Still, in our mercy and clemency, we incline to show you favour. Your flute, for which it seems you paid twenty-five pounds, is forfeited; but, for another twenty-five you may redeem it."

The orphan was dreadfully indignant.

"What!" he cried, "pay twice over for what's my own property? I won't pay another farthing, you pot-bellied old humbug."

"What does he say?" asked the bashaw of his vizier; "does he consent?"

The interpreter turned slightly green with dismay as he stammered in reply—

"He expresses himself utterly overpowered by the—the—splendour of your highness's magnificent condescension; but—a—a—at the same time he is not at the present moment able to a—avail himself of it."

"You mean to say he has no sufficient funds—is that it?"

"Yes, your highness."

The disappointed bashaw uttered an angry grunt, and looking savagely at the prisoner, said to him—

"Since you can't pay, you must——"

"I can pay," shouted the orphan, in a furiously

Comments (0)