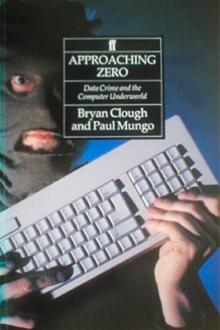

Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗

- Author: Paul Mungo

- Performer: -

Book online «Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗». Author Paul Mungo

according to this code, may break into computers or computer networks with

impunity, but should not tamper with files or programs.

In the real world it rarely works like that. Though hackers see themselves as a

useful part of the system, discovering design flaws and security deficiencies,

the urge to demonstrate that a particular computer has been cracked tempts

hackers to leave evidence, which involves tampering with the computer. The

ethical code is easy to overlook, and sometimes tampering can become malicious

and damaging.

For the authorities, the whole thing is a giant can of worms. Patrolling the

access points and communications webs that make up Worldnet is an impossible

task; in the end, policing in the information age is necessarily reactive.

Adding to the problems of the authorities is the increasing

internationalization of the computer underground. Laws are formed to cover

local conditions, in which the crime, the victim, and the perpetrator share a

common territory. International crime, in which the victim is in America, say,

and the perpetrator in Europe, while the scene of the crime—the computer that

was violated—may be located in a third country, makes enforcement all the more

difficult. Police agencies only rarely cooperate internationally, language

differences create artificial barriers, and the laws and legal systems are

never the same.

Still, the authorities are bound to try. The argument that began as the

information age dawned, encapsulated in Stephen Levy’s uncompromising view that

access to data should be “unlimited and total,” has never ended. The

government, corporations, and state agencies will never aliow unlimited access

for very obvious reasons: state security, the privacy of individuals, the

intellectual property conventions … the list goes on and on. In all western

countries, hacking is now illegal; the theft of information from computers, and

in some cases even unauthorized access, is punishable by fines and jail

sentences. The position is rigid and clear: the computer underground is a

renegade movement, in conflict with the authority of the state.

But there are still good hackers and bad hackers. And it is even true that

sometimes hackers can be helpful to the authorities—or at least, it’s happened

once. A hacker named Michael Synergy (he has legally changed his name to his

handle) once broke into the computer system at a giant credit agency that holds

financial information on 80 million Americans, to have a look at then president

Ronald Reagan’s files. He located the files easily and discovered sixty-three

other requests for the president’s credit records, all logged that day from

enquirers with unlikely names. Synergy also found something even odder—a group

of about seven hundred people who all appeared to hold one specific credit

card. Their credit histories were bizarre, and to Synergy they all seemed to

have appeared out of nowhere, as if “they had no previous experience.” It then

occurred to him that he was almost certainly looking at the credit history—and

names and addresses—of people who were in the U.S. government’s Witness Protection

Program.

Synergy, a good citizen, notified the FBI about the potential breach of the

Witness Program’s security. That was hacker ethics. But not every hacker is as

good a citizen.

Pat Riddle has never claimed to be a good citizen. He is proud of being the

first hacker in America to be prosecuted. Even now, as a thirty-four-yearold

computer security consultant, he is fond of describing cases he has worked on

in which the law, if not actually broken, is overlooked. “I’ve never been

entirely straight,” he says.

As a child growing up in a suburb of Philadelphia, he, like most hackers, was

fascinated by technology. He built model rockets, played with electronics, and

he liked to watch space launches. When he became a little older, his interests

turned to telecommunications and computers.

Pat and his friends used to rummage through the garbage left outside the back

doors of phone company offices for discarded manuals or internal memos that

would tell them more about the telephone system—a practice known as dumpster

diving. He learned how to make a “butt set,” a portable phone carried by phone

repairmen to check the lines, and first started “line tapping”—literally,

listening in on telephone calls—in the early 1970s, when he was fourteen or

fifteen.

The butt set he had built was a simple hand-held instrument with a dial on the

back and two alligator clips dangling from one end. All the materials he used

were purchased from hardware and electronics stores. To line-tap, he would

search out a neighborhood telephone box where the lines for all the local phones come together.

Every three-block area, roughly, has one, either attached to a telephone pole

or freestanding. Opening the box with a special wrench—also available from

most good hardware stores—he would attach the clips to two terminals and

listen in on conversations.

Sometimes, if the telephone box was in a public area, he would run two long

wires from the clips so that he could sit behind the bushes and listen in on

conversations without getting caught. To find out whose phone he was listening

to, he would simply use his butt set to call the operator and pretend to be a

lineman. He would give the correct code, which he had learned from his hours of

dumpster diving, and then ask, “What’s this number?” Despite being fourteen, he

was never refused. “So long as you know the lingo, you can get people to do

anything,” Pat says.

The area where he grew up was a dull place, however, and he never heard

anything more interesting than a girl talking to her date. “It was basically

boring and mundane,” he says, “but at that age any tittle-tattle seemed

exciting.”

Pat learned about hacking from a guy he met while shoplifting electronic parts

at Radio Shack. Doctor Diode, as his new friend was called, didn’t really know

much more about hacking than Pat, but the two of them discovered the procedures

together. They began playing with the school’s computer, and then found that

with a modem they could actually call into a maintenance port—a dial-up—at

the phone company’s switching office. The phone company was the preferred

target for phreakers-turned-hackers: it was huge, it was secretive, and it was

a lot of fun to play on.

Breaking into a switch through a maintenance port shouldn’t have been easy, but

in those days security was light. “For years and years the phone company never

had any problems because they were so secret,” Pat says. “They never expected

anyone to try to break into their systems.” The switch used an operating system

called UNIX, designed by the phone company, that was relatively simple to use.

“It had lots of menus,” recalls Pat with satisfaction. Menus are the lists of

functions and services available to the computer user, or in this case, the

computer hacker. Used skillfully, menus are like a map of the computer.

As Pat learned his way around the switch, he began to play little jokes, such

as resetting the time. This, he says, was absurdly simple: the command for the

clock was Time. Pat would reset the clock from a peak time—when telephone

charges were highest—to an off-peak time. The clock controlled the telephone

company’s charges, so until the billing department noticed it was out of

kilter, local telephone users enjoyed a period of relatively inexpensive

calls. He also learned how to disconnect subscriber’s phones and to manipulate

the accounts files. The latter facility enabled him to “pay” bills, at first at

the phone company and later, he claims, at the electric company and at credit

card offices. He would perform this service for a fee of 10 percent of the

bill, which became a useful source of extra income.

He also started to play on the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects

Agency (ARPA) computer network. ARPANET was the oldest and the largest of the

many computer nets—webs of interconnected mainframes and workstations—that

facilitated the Defense Department’s transfer of data. ARPANET was conceived in

the 1950s—largely to protect the ability of the U.S. military to communicate

after a nuclear strike—and finally established in the late 1960s. It

eventually linked about sixty thousand computers, or nodes, and interacted with

other networks, both in the United States and elsewhere in the world, making it

an integral part of Worldnet. Most universities, research centers, defense

contractors, military installations, and government departments were connected

through ARPANET . Because there was no “center” to the system, it functioned

like a highway network, connecting each node to every other; accessing it at

one point meant accessing the whole system.

Pat used to commune regularly with other hackers on pirate bulletin boards,

where he exchanged information on hacking sites, known computer dial-ups, and

sometimes even stolen IDs

and passwords. From one of these pirate boards he obtained the dial-up numbers

for several ARPANET nodes.

He began his hack of ARPANET by first breaking into Sprint, the long-distance

phone carrier. He was looking for long-distance access codes, the five-digit

numbers that would get him onto the long-distance lines for free. In the old

days he could have used a blue box, but since then the phone system had become

more sophisticated. Blue boxes were said to have been killed off once and for

all in 1983 when Bell completed the upgrading of its system to what is called

Common Channel Interoffice Signaling (CCIS). Very simply, CCIS separates the

signaling—the transmission of the multifrequency tones—from the voice lines.’

To get the codes he wanted, Pat employed a technique known as war-dialing, in

which a program instructs the computer to systematically call various

combinations of digits until it finds a “good” one, a valid access code. The

system is crude but effective; a few hours spent war-dialing can usually garner

a few good codes.

These long-distance codes are necessary because of the timeconsuming nature of

hacking. It takes patience and persistence to break into a target computer, but

once inside, there is a myriad of menus and routes to explore, to say nothing

of other linked computers to jump to. Hackers can be on the phone for hours,

and whenever possible, they make certain their calls are free.

Pat’s target was an ARPANET-linked computer at MIT, a favorite for hackers

because at that time security was light. In common with many other

universities, MIT practiced a sort of open access, believing that its computers

were there to be used. The difficulty for MIT, and other computer operators, is

that if security is light, the computers are abused, but if security is tight,

they become more difficult for even authorized users to access.

Authorized users are given a personal ID and a password, which hackers spend a

considerable amount of time collecting through pirate bulletin boards, peering

over someone’s shoulder in an office, or “dumpster diving.” But exploiting a

computer’s default log-ins and passwords can often be even simpler—as Nick

Whiteley discovered when he hacked in to the QMC computer for the first time. A

common default is “sysmaint,” for systems maintenance, used as both the log-in

and the password. Accessing a machine with this default would require no more

than typing “sysmaint” at the log-in prompt and then again at the password

prompt. Experienced hackers also know that common commands such as “test” or

“help” are also often used as IDs and passwords.

Pat first accessed ARPANET by using a default code. “Back then there was no

real need for security,” he says. “It was all incredibly simple. Computers were

developed for human beings to use. They have to be simple to access because

humans are idiots.”

ARPANET became a game for him—he saw it as “a new frontier to play in.” He

jumped from computer to computer within the system,

Comments (0)