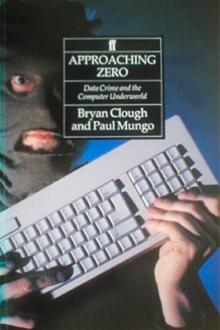

Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗

- Author: Paul Mungo

- Performer: -

Book online «Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗». Author Paul Mungo

Approaching Zero

–—

The Extraordinary Underworld of Hackers,

Phreakers, Virus Writers,

And Keyboard Criminals

–—

Paul Mungo

Bryan Glough

*****

This book was originally released in hardcover by Random House in 1992.

I feel that I should do the community a service and release the book in the

medium it should have been first released in… I hope you enjoy the book as

much as I did..It provides a fairly complete account of just about

everything…..From motherfuckers, to Gail ‘The Bitch’ Thackeray…..

Greets to all,

Golden Hacker / 1993

Death Incarnate / 1993

*****

––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Golden Hacker and Death Incarnate were to lazy to do anything more than to put

the book on a scanner and run an OCR on what it produced. There were however

several small errors in the text - obviously result of OCRing it and not

reading afterwards. I corrected most of them while reading the book from the

screen. It is really worth reading - altough it shows hacker community from

lamers point of view. Maybe someone will make TeX file of that, I’m too lazy,

as I already read it <grin>

Emin <1993>

P.S. Steve Jackson won his case against SS and they will have to pay for their

ignorance during witch hunts…

––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Fry Guy watched the computer screen as the cursor blinked. Beside him a small

electronic box chattered through a call routine, the numbers clicking audibly

as each of the eleven digits of the phone number was dialed. Then the box made

a shrill, electronic whistle, which meant that the call had gone through; Fry

Guy’s computer had been connected to another system hundreds of miles away.

The cursor blinked again, and the screen suddenly changed. WELCOME TO CREDIT

SYSTEMS OF AMERICA, it read, and below that, the cursor pulsed beside the

prompt: ENTER ACCOUNT NUMBER.

Fry Guy smiled. He had just broken into one of the most secure computer systems

in the United States, one which held the credit histories of millions of

American citizens. And it had really been relatively simple. Two hours ago he

had called an electronics store in Elmwood, Indiana, which—like thousands of

other shops across the country—relied on Credit Systems of America to check

its customers’ credit cards.

“Hi, this is Joe Boyle from CSA … Credit Systems of America,” he had said,

dropping his voice two octaves to sound older—a lot older, he hoped—than his

fifteen years. He also modulated his natural midwestern drawl, giving his voice

an eastern twang: more big-city, more urgent.

“I need to speak to your credit manager … uh, what’s the name? Yeah, Tom.

Can you put me through?”

Tom answered.

“Tom, this is Joe Boyle from CSA. You’ve been having some trouble with your

account?”

Tom hadn’t heard of any trouble.

“No? That’s really odd…. Look, I’ve got this report that says you’ve been

having problems. Maybe there’s a mistake somewhere down the line. Better give

me your account number again.”

And Tom did, obligingly reeling off the eight-character code that allowed his

company to access the CSA files and confirm customer credit references. As Fry

Guy continued his charade, running through a phony checklist, Tom, ever

helpful, also supplied his store’s confidential CSA password. Then Fry Guy

keyed in the information on his home computer. “I don’t know what’s going on,”

he finally told Tom. “I’ll check around and call you back.”

But of course he never would. Fry Guy had all the information he needed: the

account number and the password. They were the keys that would unlock the CSA

computer for him. And if Tom ever phoned CSA and asked for Joe Boyle, he would

find that no one at the credit bureau had ever heard of him. Joe Boyle was

simply a name that Fry Guy had made up.

Fry Guy had discovered that by sounding authoritative and demonstrating his

knowledge of computer systems, most of the time people believed he was who he

said he was. And they gave him the information he asked for, everything from

account codes and passwords to unlisted phone numbers. That was how he got the

number for CSA; he just called the local telephone company’s operations

section.

“Hi, this is Bob Johnson, Indiana Bell tech support,” he had said. “Listen, I

need you to pull a file for me. Can you bring it up on your screen?”

The woman on the other end of the phone sounded uncertain. Fry Guy forged

ahead, coaxing her through the routine: “Right, on your keyboard, type in K—P

pulse…. Got that? Okay, now do one-two-one start, no M—A…. Okay?

“Yeah? Can you read me the file? I need the number there….”

It was simply a matter of confidence—and knowing the jargon. The directions he

had given her controlled access to unlisted numbers, and because he knew the

routine, she had read him the CSA number, a number that is confidential, or at

least not generally available to fifteen-year-old kids like himself.

But on the phone Fry Guy found that he could be anyone he wanted to be: a CSA

employee or a telephone engineer—merely by pretending to be an expert. He had

also taught himself to exploit the psychology of the person on the other end of

the line. If they seemed confident, he would appeal to their magnanimity: “I

wonder if you can help me …” If they appeared passive, or unsure, he would

be demanding: “Look, I haven’t got all day to wait around. I need that number

now.” And if they didn’t give him what he wanted, he could always hang up and

try again.

Of course, you had to know a lot about the phone system to convince an Indiana

Bell employee that you were an engineer. But exploring the telecommunications

networks was Fry Guy’s hobby: he knew a lot about the phone system.

Now he would put this knowledge to good use. From his little home computer he

had dialed up CSA, the call going from his computer to the electronic box

beside it, snaking through a cable to his telephone, and then passing through

the phone lines to the unlisted number, which happened to be in Delaware.

The electronic box converted Fry Guy’s own computer commands to signals that

could be transmitted over the phone, while in Delaware, the CSA’s computer

converted those pulses back into computer commands. In essence, Fry Guy’s home

computer was talking to its big brother across the continent, and Fry Guy would

be able to make it do whatever he wanted.

But first he needed to get inside. He typed in the account number Tom had given

him earlier, pressed Return, and typed in the password. There was a momentary

pause, then the screen filled with the CSA logo, followed by the directory of

services—the “menu.”

Fry Guy was completely on his own now, although he had a

good idea of what he was doing. He was going to delve deeply into the accounts

section of the system, to the sector where CSA stored confidential information

on individuals: their names, addresses, credit histories, bank loans, credit

card numbers, and so on. But it was the credit card numbers that he really

wanted. Fry Guy was short of cash, and like hundreds of other computer wizards,

he had discovered how to pull off a high-tech robbery.

When Fry Guy was thirteen, in 1987, his parents had presented him with his

first computer—a Commodore 64, one of the new, smaller machines designed for

personal use. Fry Guy linked up the keyboard-sized system to an old television,

which served as his video monitor.

On its own the Commodore didn’t do much: it could play games or run short

programs, but not a lot more. Even so, the machine fascinated him so much that

he began to spend more and more time with it. Every day after school, he would

hurry home to spend the rest of the evening and most of the night learning as

much as possible about his new electronic plaything.

He didn’t feel that he was missing out on anything. School bored him, and

whenever he could get away with it, he skipped classes to spend more time

working on the computer. He was a loner by nature; he had a lot of

acquaintances at school, but no real friends, and while his peers were mostly

into sports, he wasn’t. He was tall and gawky and, at 140 pounds, not in the

right shape to be much of an athlete. Instead he stayed at home.

About a year after he got the Commodore, he realized that he could link his

computer to a larger world. With the aid of an electronic box, called a modem,

and his own phone line, he could travel far beyond his home, school, and

family.

He soon upgraded his system by selling off his unwanted possessions and bought

a better computer, a color monitor, and various other external devices such as

a printer and the electronic box that would give his computer access to the

wider world. He installed three telephone lines: one linked to the computer for

data transmission, one for voice, and one that could be used for either.

Eventually he stumbled across the access number to an electronic message center

called Atlantic Alliance, which was run by computer hackers. It provided him

with the basic information on hacking; the rest he learned from

telecommunications manuals.

Often he would work on the computer for hours on end, sometimes sitting up all

night hunched over the keyboard. His room was a sixties time warp filled with

psychedelic posters, strobes, black lights, lava lamps, those gift-shop relics

with blobs of wax floating in oil, and a collection of science fiction books.

But his computer terminal transported him to a completely different world that

encompassed the whole nation and girdled the globe. With the electronic box and

a phone line he could cover enormous distances, jumping through an endless

array of communications links and telephone exchanges, dropping down into other

computer systems almost anywhere on earth. Occasionally he accessed Altos, a

business computer in Munich, Germany owned by a company that was tolerant of

hackers. Inevitably, it became an international message center for computer

freaks.

Hackers often use large systems like these to exchange information and have

electronic chats with one another, but it is against hacker code to use one’s

real name. Instead, they use “handles,” nicknames like The Tweaker, Doc Cypher

and Knightmare. Fry Guy’s handle came from a commercial for McDonald’s that

said “We are the fry guys.”

Most of the other computer hackers he met were loners like he was, but some of

them worked in gangs, such as the Legion of Doom, a U.S. group, or Chaos in

Germany. Fry Guy didn’t join a gang, because he preferred working in solitude.

Besides, if he started blabbing to other hackers, he could get busted.

Fry Guy liked to explore the phone system. Phones were more than just a means

to make a call: Indiana Bell led to an immense network of exchanges and

connections, to phones, to other computers, and to an international array of

interconnected phone

systems and data transmission links. It was an electronic highway network that

was unbelievably vast.

He learned how to dial

Comments (0)