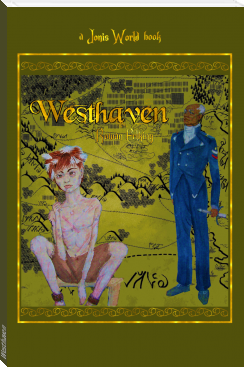

Westhaven, Rowan Erlking [large ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Rowan Erlking

Book online «Westhaven, Rowan Erlking [large ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Rowan Erlking

“Well, what do you think?” Gailert turned to General Lemmun.

Closing one eye, General Lemmun peered at the boy for a full two minutes. Then he grunted and sat back. “He doesn’t look that smart.”

Gailert gave a laugh.

“Just trust me. He’s working out well. I got him trained to fetch things. He knows more than most humans. Watch this—” He waved to the boy and said, “Go get me the dictionary.”

The boy blinked, turned his head and looked around the room. He hesitated then apprehensively stepped towards the bookshelf across the room. Dropping the blanket on the stool, the boy stood up to where he touched the binding of several of the large volumes there. He paused several times before selecting one and carrying it back to the table where Gailert had his tea.

“You said dictionary. This is my atlas,” General Lemmun said with a snicker.

Gailert sighed.

“It does look like my dictionary. Same color and size.” He then peered at the boy who was hanging his head as if waiting for his ears to be boxed. “I don’t suppose you know how to read, do you?”

The boy looked up. He paused, searching to see if he was meant to speak.

Gailert waited.

The boy at last said, “No, sir.”

“How do you learn without knowing how to read?” Gailert asked him.

Knowing now that the man was waiting for response, the boy who had said not much more than yes, sir, no, sir choked and then licked his lips before whispering. “I watch, sir.”

“Do you want to know how to read?” Gailert asked him.

His eyes growing wide, the boy opened his mouth but hardly could speak.

“Can’t he talk? Is he an idiot?” General Lemmun exclaimed.

But Gailert shook his head. “Not an idiot. But I do think he is afraid.”

The boy ducked his head.

“It would be handy for me if he could read,” Gailert murmured aloud. “He could fetch things for me by reading the signs and covers. And that would be such a time saver.”

“But teaching a slave to read is also dangerous,” General Lemmun said, lifting his teacup again to peer at the insides. “And though I realize that you are an idealist with dreams of civilized humans, I must say that you really ought to start with a cultured, more passive human than some former…whatever he was.”

“Laborer?” Gailert asked with a smirk. “Really, Lemmun, don’t you think that an educated laborer would ease the troubles of management?”

The retired general merely shrugged. “I suppose. But I can’t stand the idea of some slave reading labels for poisons.”

“The humans have used a writing system, you know,” Gailert said.

“Which scribes, patriarchs, and magicians used,” General Lemmun said. “The common folk are too simple to understand it.”

Gailert laughed and rose from his seat. “Coming from a man who remembers a history of a ninety percent literacy rate of a population, I find your argument ironic.”

The boy seemed to wobble on his feet, yet he remained at attention as if afraid to move. Gailert picked up the wool blanket and put it back on the boy’s shoulders. He then directed the boy to the bench.

“No watermark,” General Lemmun warned with a chuckle.

Grinning back with a shake of his head, Gailert picked up a blank sheet of paper and a nib pen off of the desk, also taking up the ink well. He put all three things on the small table next to the bench. The boy shook, peering at him as Gailert started to write out letters on the page. “Boy, I am going to teach you how to write and read. Once you have learned this, you are going to do much more useful work for me. Now this letter is called Bet. Say it, Bet.”

The boy looked up at him and then sighed, repeating, “Bet.”

“Good. Now take this pen, and write Bet for me,” Gailert said.

But this did not go as smoothly. Gailert had to reposition the boy’s hold of the pen. The child had first held it like he would a knife to stab someone then he held it like human peasant eating sticks. In the end, Gailert had to position his pen and hold the boy’s hand in the correct position, dip the pen and then help him write the shape.

“Write it and say it,” Gailert said, forming the letter. “Bet.”

Sighing, clenching the pen, the boy scratched out a shaky shape. “Bet. Bet. Bet. Bet….”

“Keep it up and go across the page,” Gailert said. “Then I will show you the next letter.”

“Bet. Bet. Bet. Bet. Bet. Bet….”

“How can you stand that? It is so tedious,” General Lemmun said.

There was a smile on Gailert’s lips as he answered. “Didn’t even you have to practice the writing when they handed you the memory of the letters?”

Huffing, the retired general lifted his shoulders. “Well, yes. Of course. A passed on memory does not account for muscle memory. But repeating Bet over and over again is so tiresome.”

Gailert’s smile had not vanished. “Yes, but that is how those who learn their knowledge firsthand acquire memory. And believe me, after this work, this child will not forget his letters—much better than those who take for granted a memory merely passed on to them.”

General Lemmun only shrugged and sipped the rest of his tea.

“Now for letter Ket. It looks like Bet only it is wider and the shape goes down like this and up like this,” Gailert said. “Now repeat it and say Ket.”

“Ket. Ket. Keh…ke…eh…eh…choo!”

The boy sneezed then rubbed his nose. Black ink smeared from his stained fingers across his face.

General Lemmun snorted, covering a laugh. “Oh, yes. He’s catching on. Just make sure he doesn’t use that ink for war paint.”

“Just drink your tea,” Gailert said, and reached into his pocket for a handkerchief, wiping his boy’s face.

*

Kemdin peered at his ink-stained fingers that night as he lay on his back. The sounds of the letters repeated in his head over and over again like the boom of a drum. Bet, Ket, Det, Fet, Get, Het, Jit, Let, Men, Nen, Chet, Than, Pen, Ran, Set, Shat, Tet, Vin, Wan, Yit, and Zan. The general said he would teach him the vowels later. Kemdin already knew his numbers. That had impressed the general, though the other one did not seem as much impressed. The two Sky Children had talked about the state of a thing called the educational system and literacy after Kemdin had finished copying each symbol he had memorized. And though Kemdin knew the names of the marks, he still did not understand why he had to learn them or what they meant. All he knew was that he had to learn them or he would anger the general.

Closing his eyes, the list of shapes and their names repeated. Bet, Ket, Det, Fet, Get, Het, Jit, Let, Men, Nen, Chet…. Their vertical marks like slashes on the page were familiar in a way. He had seen them before. In fact, they were everywhere, but Kemdin had assumed they were decoration, designs like those his father had put on his swords.

Writing. It was something new. Not like tallying, which he understood. Now Reading? Listening to the old men, there was one thing Kemdin did understand, and that was if he learned these marks he would know things that most humans did not. Hidden in these marks was a secret knowledge of the ancients that the magicians used. If was to read, then he would learn to read everything.

[1] See the Jonis Scrolls if you are interested in knowing all the varieties of demons.

[2] To know the differences between witches, magicians, and wizards in this world, read the Jonis Scrolls.

Chapter Four: Up and Down Hills

The boy was an astute learner. General Winstrong was right about the child’s ability to absorb information and use it. The boy had gone from writing his letters and numbers from memory in a week to reading the writing off of the covers of the general’s library books and fetching documents. He wasn’t as fast as a Sky Child his age that had learned from passed memory, but his skill did equal that of a brown-eyed that learned writing. In fact, he was faster. That troubled Gailert some.

Watching the boy during his errands, Gailert noticed how the child’s eyes flickered from the signs on the street, reading every single one of them, to the writing on packages, address labels, and most startlingly, the wall map at the military post. Though the boy still did not talk unless ordered to, a much-appreciated trait to be sure, his eye did show that he understood much of the conversations around him and he listened intently. Because of that, Gailert came to a sad but necessary conclusion.

“Boy!” He called into the dark cellar. It was long after supper and his porter had sent the boy to bed hours ago. Saimon himself was resting in his quarters as it was very late. “Come up here.”

The boy’s chains rustled. Gailert could hear the child rise from the floor. Shuffling from the weight of his bonds, the boy crossed the room then climbed the stairs, stopping midway when he could see Gailert’s face. “Yes, sir?”

“I have been watching you, and I know you are up to something,” Gailert said.

The boy’s eyes widened. “No, sir.”

The defiance was insufferable. Just seeing it, just hearing it, Gailert swung out and struck the child across the face. “How dare you defy me? I’ve been watching you! You have been reading everything in front of you! Even private documents and military maps!”

Clenching his face, the boy ducked against the wall. “But you wanted me to read!”

Gailert struck him again. The boy fell backward, rolling down the stairs. His body flopped, landing a yard from the foot of the steps. Stomping down after him, Gailert bent over and heaved the child off the floor by his arms and shook him.

“You will not be insubordinate! What have you read?” He shouted.

Already the boy was making that irritating crying, his chains rattling as he tried to cover his face from more blows, or perhaps to hide his eyes that would show what he was really thinking.

Dropping him to the ground, Gailert kicked at him. “What have you read?”

The boy continued to wordlessly cry, lifting his arms up to protect himself.

“What have you read?” the general shouted again.

“Everything!” the boy cried out, flopping against the ground. “You wanted me to read!”

Gailert kicked him again. “If you don’t tell me, I’ll have Saimon suck it out of you.”

The boy only sobbed louder, his voice like a wail.

Kicking out once more, Gailert stomped back up the stairs. “You leave me no choice.”

It was twelve paces to the porter’s room. Gailert had to wake him. Saimon was irritable when he at last understood the charge he laying on him. When they both returned to the cellar the boy was no longer at the foot of the stairs. Calling out, they searched the room and found him ducked behind the furnace, as if he could claw through the rock to get

Comments (0)