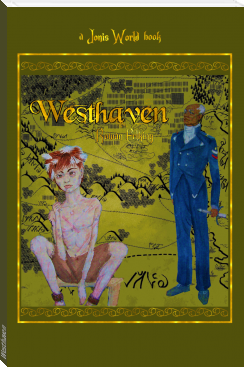

Westhaven, Rowan Erlking [large ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Rowan Erlking

Book online «Westhaven, Rowan Erlking [large ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Rowan Erlking

“There is one rule in this house.” The porter turned before going up. “Do what I say. And I say, speak only when you are spoken to. I say, do exactly as you are told without a word. I say, do not touch anything in this room or in the rest of the house.” The porter’s face tightened with each sentence. “I say, do only what you are told. For if you disobey me I will not only beat you within an inch of your life, but I will also make sure that you are forever hungry—no matter what the master says.

“And if you tell him that I have disobeyed him, I will cut off the tips of your fingers, your nose, your ears, and any other appendage that sticks out until you are nothing left but a head and a body. Then I will deliver you personally to a Gole so he can eat out your heart while it still beats. Understand?”

Kemdin pulled his arms and legs close to his body, nodding vigorously. “Yes…sir.”

The demon nodded then walked up the stairs to the upper floor.

It had been a cruel trick. Entering the home, seeing the enormity of it, Kemdin had believed that maybe it would not be so bad. But here in the darkness lit only by the glow of the hearth he was put back into the place these demons wanted him. He was property and a prisoner. Returning home was no longer even a slight possibility. He was captive for good.

*

The morning after his return, just after he had a good breakfast and was dressed, Gailert marched down to the cellar where the boy was sleeping on the ground. Undoubtedly the boy had been terrorized a bit by his porter the night before, but that was to be expected. The child had to learn to respect his masters before they could start with anything else.

He called to his porter. “Take the boy out to the yard in back and have him washed. I want him in clean breeches, no shirt. When he learns to behave correctly, we’ll provide him with a shirt. Until then, he will learn his place. Then bring him to me when he is ready.”

The porter bowed and then turned his eyes to the child. The boy was already staring up at them both with horror, perhaps gaining more white hairs.

Turning, Gailert marched back upstairs and to his study to read his mail, study the legal forms sent to him during his absence, and sign the necessary documents for the continuation of work within his district. It took a few hours to do, but it filled the time it took to wait for the return of his new acquisition. His porter held the boy by his arm, shoving the scrubbed child to his knees on the study’s carpet.

Gailert peered down at the boy and reached over to his face inspecting the tense yet still hostile look in the child’s eyes. He lifted the boy’s chin and said, “You know, there are people who believe that the history of one man can be read simply from looking into his eyes.”

The boy’s eyes flickered, looking to the general’s as if to read them. It made Gailert smile.

“Your eyes have flecks of gray and yellow in them. I see small holes that indicate pain,” he said. “Perhaps you broke an arm when you were a very young.”

But then he glanced down and touched the obvious burn mark on the boy’s chest. It was practically square; the size of a coin, yet indented just above the sternum leaning towards his heart.

“Oh. That’s right. I had forgotten.” Gailert felt the boy tremble as he touched the scar. “You were the intended sacrifice that day. Funny how life changes on a pin tip.”

The boy’s chest heaved as if he wished to pounce on the general. But he held his place, though the porter boxed the boy’s ears, forcing the child to cower again.

Gailert rose. “I see. We have much work to do with you.”

Of course, the general wondered where to start. The idea of a boy doing odd jobs for him around the home and on his journeys had sounded like a good idea at the time, but with that wild thing kneeling there in his study he was starting to wonder which tasks to start with.

With a shrug, he said, “Alright. I have it. You will train with house cleaning first. You will do everything my man, Saimon, here tells you to do. You will mostly carry things for us until you are stronger and steadier for other work.”

The boy lowered his head.

The porter boxed his ears. “What do you say, boy?”

Cringing, his new slave looked up at his new master though there was spite on his face. “Yes, sir.”

“Good.” Gailert sighed and turned back to his work, taking up yet another document and scanning the contents. “Go to it immediately.”

The porter yanked on the boy’s arm. “Follow me. We have work in the yard first. Then you will help the cook.”

The child looked back only once at Gailert before going.

*

Kemdin felt there was something strange about that brown-eyed Sky Child. Besides being a murderer, he talked as if such bloody things were merely like catching fish for supper. Sure, the demon fed him meat, bread and milk and the occasional potato, but that was like feeding an animal to keep up his strength. Yet when Kemdin worked in the yard carrying the wood pieces the gardener had chopped for the fire, General Gole stood in the doorway and watched him much in the same way his uncle had watched him and his father forge arrowheads. And when he had been made to pluck the chickens for the general’s supper then clean up the feathers, the demon laughed as if he were truly amused.

Then there was the way the general regularly summoned Kemdin into his study, making him sit on a chair of that amazingly furry fabric and listen to him lecture from one of his strange books from his library. Most of it was boring talk with words like ‘economy’ and ‘gross national product’ and ‘transportation’ again. He used the word ‘progress’ a lot, and described humans as ‘medieval’, whatever that meant. Then after the hours were spent and the sun had gone low in the sky, the general often walked him down the cellar stairs himself to where he had the maids create a small bed for Kemdin on the ground so that he could be awake early the next morning for the day’s work all over again.

General Gole—or rather General Gailert Winstrong as the people who came in and out of the house called him—was like that fabled two tongued demon who in stories could transform into a snake and a human that constantly tricked and lured people away into his den. He spoke silvery tongued to many of those that he did business with, wealthy humans and blue-eyes alike. But when the general was among the soldiers, he spoke harsh and brisk just as he had in the village. He dragged Kemdin along to carry things for him on errands in the city. At least then he was allowed to ride inside the back seat rather than in the trunk with their parcels. But his view of the double-tongued demon let him know that General Gailert Winstrong was dangerous even among the other Sky Children.

People bowed to the general everywhere they went on foot. Kemdin trailed after him in his bare feet and chains, often shaking from the weight of his chains on his legs that prevented him from keeping up when the general walked fast. When the general wanted him, he merely called Kemdin boy then expected him to hurry. One of the wealthy humans once asked Kemdin’s name, but Kemdin was not allowed to speak unless the general allowed it. And he didn’t. The general had answered for him, “He has no name.”

The human had paled and bowed his head, apologizing for asking.

That was how it was. He was the boy. He was called Winstrong’s boy. He was the general’s boy. No one spoke to him directly unless they were ordering him to take the general something. That usually happened when he was with the general at the military office, often sitting on the stoop waiting for the general to order him about and carry something. Those that ordered him there never expected him to speak. In fact, Kemdin often went through a day without uttering one word. So when it was night and he was sure the general and all the house staff were asleep he would whisper to the fire words to songs his mother and father had taught him.

After the first month, Kemdin went with the general to the neighboring city of Gibbis where they stayed with another Sky Child general, though this one had blue eyes and a more wrinkled face. He also had a human slave, a footman who wore a prim vest over his bare chest, laced up, with leather wrist cuffs to remind him he was still a captive. That man’s legs were not chained either. But the way the young man walked it was as if he were still chained. The footman hardly looked at Kemdin when he escorted the general to his quarters, and he said not one word when he rolled into his bed in the servants’ wing that night where Kemdin was tossed a blanket and a stiff pillow against the growing cold of the autumn. Even in the morning after, the footman said no word to him but tugged on Kemdin’s ear to gesture where they would have to go to help out the staff.

The cook was in charge here. She was also the head maid, called the lady of the house. “You, boy. Carry this.”

She dropped a heavy pot into his arms then turned expecting for him to follow. The lady of the house was a brown-eyed Sky Child perhaps only a bit younger than the general herself. Most of the staff in the house was human. Half of them had leg irons. Not one spoke when the cook was around. However, when she was gone they started to whisper. Despite that, Kemdin was to be with her the entire day unless the general called for him.

“I don’t know if I can trust you with a knife,” the cook said, gesturing for Kemdin to set the pot on a stove.

She had another servant already stoking the fire. That one was a young woman with burns on her hands. Her leg irons looked tight, and her ankles were swollen. She ducked when the cook lifted up an iron poker.

“You, hurry it up with the fire!” The cook jabbed the girl with the poker before handing it to her. The lady of the house then turned on Kemdin, shoving a bucket of potatoes at him. “Wash these and then peel them.”

Kemdin caught the weight of the bucket and backed into where there was a worn wood stool. He took up the empty bucket another servant handed him while gesturing to the pump for water. There were many things Kemdin had learned about the Sky Children. One was that they had ways of making water rise from their wells without magic. The general called it a hand pump. The porter called the pipes that came from the furnace to the cellar ceiling plumbing. All of these things were new, but things he was expected to know now that he was a Sky Child’s slave. So, going to the hand pump, he filled it full of water and carried it back to his stool to wash the potatoes.

As he scrubbed each potato with cold water then piled them in a clean bucket, Kemdin listened to the bustle and whispers of the servants of this house. The cook worked on her bread, mixing, kneading and then shaping them into

Comments (0)