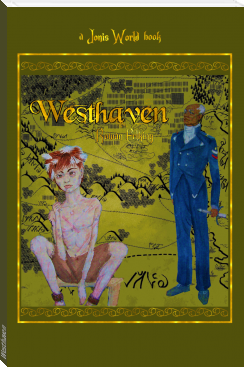

Westhaven, Rowan Erlking [large ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Rowan Erlking

Book online «Westhaven, Rowan Erlking [large ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Rowan Erlking

“Quite an effective deterrent.” Mr. Pennerly gave a nod to his friend.

“I see.” Gailert rose from his chair. “And how many insurgents have you executed?”

The two men exchanged looks, thinking about it.

“Sixteen?”

“Seventeen.”

“Something like that.”

Nodding, the general then asked, “And how was public reaction?”

Mr. Pennerly gave a small shrug, dabbing his sweating neck with his handkerchief. “The initial reaction was expectedly shocked and horrified. But, uh, the people are more used to it now. They expect us to come down hard.”

“And how much have the instances of insurgence been reduced by this?” Gailert asked.

The businessman grinned. “Magnificently. We had an outbreak in the beginning, but they have almost completely died out. We hardly have any trouble these days.”

“But you said almost.” Gailert inspected his looks. “What kind of trouble remains?”

Nodding, the man replied, “Well, these days the insurgents are more specialized and harder to catch. They aren’t locals. That is certain.”

“Lone gunmen?” Gailert leaned back, looking to the men as he started to draw up conclusions.

Mr. Pennerly blinked, paused and nodded. “In a way. More like terrorists. Now you see them, now you don’t. Poisonings, stabbings, and they set fire with small flammable explosives or pull loose wires to homes to electrocute particular individuals.”

“You mean humans that understand technology and are using it against you.” Stiffened, the general knew that this town had been too good to be true.

“General,” Mr. Pennerly said as frankly as he could. “The humans are survivors. They will adapt one way or the other. We are going to have both whether we like it or not. Preferably, I want the ones adapting to our ways at our sides, rather than us trying to crush them all and they adapt, stealing our ways to destroy us.”

Gailert frowned, knowing in a defeated way that the man was right. The real trouble was how to defeat those that would not join them no matter what.

*

It was early morning when the general had his men carry Kemdin into the constable’s station to be marked. Fanning himself with a blank document, the constable cast the boy a side look and then shrugged. “Fine. We’ll go down smithy row and have him branded.”

The boy flinched. Looking up at the general and then the lieutenant, he wordlessly gaped at the news. He had never forgotten the searing heat of that fire iron against his chest. Over and over in his head, he asked himself what he had done wrong this time to offend the general. Had the general found out that the scullery maid had fed him and given him a pillow? The general didn’t look angry. He talked in his business tone, which meant he was safe. But it wasn’t the first time the general suddenly had him punished without explanation.

“Here it is,” the constable said. He then pointed to the boy’s feet. “I recommend that you have those leg irons taken off and his feet treated first. I’ll instruct our man here with the particulars. But, you know, you ought to mark your boy with some sort of indication that he is your property or the local children may throw rocks at him.”

“Throw rocks at him?” The general sounded surprised.

“For being a rebel’s son,” the constable said. “So if you want to protect your property, have someone tattoo your name and a recognizable insignia right next to the brand so no one will miss it. Otherwise, your boy could be dead tomorrow.”

The general’s boy pulled back now with all the strength he had. “No, please!”

The general struck the boy’s ear with his fist. “Enough of that! I told you not to contradict me.”

“He scared he is going to get killed,” the lieutenant said. “You can’t exactly blame him for being afraid.”

“That’s enough out of you also,” the general snapped at the lieutenant. “I will have a distinguishable mark on this boy that no one would dare lay a finger on him unless on my command.”

The lieutenant merely shrugged and looked away.

They carried the boy further into town towards a road where there were several smithies. One had been recommended to them. They took the boy into the front half of a smith shop and set him on the ground while the corporals found a stool for the general and the lieutenant. Both men sat as the constable went in to summon the smithy and explain what the general wanted from him.

The smithy emerged from the back of the shop. He peered over at the boy through eyes as dark as the general’s, though they were bloodshot. Gazing from a face that was red, especially on the cheeks as if they had been seared from standing too close to a hot fire though his smell proved he had merely been drinking rum, the smithy grinned. Rubbing his plump roll of fat with his raw dark hands, he spoke in a low gravelly voice. It was nothing like the warm deep base the boy remembered coming from his father. This smithy was crass and dirty.

With a snort, the smithy rubbed the edge of his leather apron as the constable gestured to the general. He stuck up his nose when the constable pointed to the boy. Sauntering over, the smithy merely bowed to the general, not even daring to offer a soiled hand. “Hello, sir. It is an honor to have the famous General Winstrong in my shop. I hear you want me to fit new irons on this here boy after we brand him. That’s fine. But, uh, what kind of compensation are we talking about for this service?”

The general’s mouth curled up on one end, peering at the face of this low Sky Child laborer.

“Compensation? Hmm?” The general rose off of his stool. “The cost of the iron, of course is required. You do have shackles for adults on hand, don’t you?”

With a short glance over his shoulder, the smithy replied, “I have some on hand, though the constable here says you want permanent irons on him.”

“That’s right,” the general said, raising his chin.

“Well that takes labor,” the smithy said, his mouth broadening into a smile. “Welding irons shut takes labor and extras so your kid’s legs don’t burn off.”

With a lurch, the boy pulled back from the smithy.

A corporal caught the boy around his arm and neck, and held him so that he could not scoot away. The smithy cast the general’s slave a dark smile, revealing a number of brown teeth and a few gaps.

However, the general nodded. “I will pay for the extras. Now may we begin? I would like to get back on my route overseeing the work in this area.”

With a huff and a nod, the smithy turned and waved them further into the shop.

The smell of it was damper than the boy remembered his father’s smith shop. Flies circled around in the air, attracted to whatever was giving off a revolting mildew stench.

“Come this way. Let’s get the first irons off.”

The corporal who was holding the boy down heaved him off the floor and dragged him inside. He set the general’s slave onto the edge of a bench right next to where the furnace was already burning coals. Not that the boy went without a fight. The boy struggled, his eyes darting from the fire to the rows of branding irons and chains with manacles on them, as well as the neck collars and animal traps the man had cast and molded.

“Help me hold him!” The corporal called to the others.

Another jumped and grabbed a firm grip on the boy’s other side to hold him down.

Letting out a low whistle, the smithy peered down at the boy’s ankles. He then glanced to the general. “Yeah. I’d say new irons are overdue. I’m surprised the kid can walk at all.”

“Will it be hard to remove them?” General Winstrong asked peering at the swollen flesh.

“He may bleed a bit. And the swelling may get pretty bad. But, uh, I can get them off.” The smith crouched down and flipped through a ring of keys that he took off of a hook on the wall. “You don’t happen to have the key to these, do you?”

“Never had one,” the general said. “Otherwise I would have taken them off myself.”

The smithy chuckled. “Good thing I have an all-key.”

“A what key?” the general asked.

Glancing at the blue-eyed soldiers with the general, the smithy shrugged. “I don’t know that the others call them, but a key that can open almost any lock.”

“Skeleton key,” the lieutenant said with the corporals nodding to him.

“Whatever.” The smithy murmured, taking the key from the ring. It was a small thing and hard to hold with all the other keys in the way. He stuck the key into the hole of the left iron and picked the lock. It stuck for bit, but that only made the smithy go back to his work desk for oil to grease the insides. It took some pressure, but the pieces inside the lock turned and the ankle brace clicked. He pried the shackle open with a chisel.

The pain was excruciating.

Howling, the boy clenched the wood bench as the metal dislodged from his skin. Underneath the manacle was all black and blue. The veins were pressed and swollen. Along edge, the skin bled.

The lieutenant hopped up. “I’ll get bandages and something to clean that up.”

“Get an antiseptic.” The general called after him.

The lieutenant was out like a shot, running into the street.

The smithy started on the other ankle. “Hold him down.”

Already the boy squirmed, his eyes ogling at the dent in his ankle as his veins throbbed even more than when they were restrained in iron. The pulsing killed. Sweat broke out all over his forehead and chest.

One of the corporals clenched him tighter, whispering into his ear. “Hold still. It will soon be over.”

The other shackle came loose more easily. But this one felt as if his skin had come off with the metal. One of the men jumped up. “My lord! Look at that!”

“A cyst,” the smithy said.

“It looks like we’ll need a medical kit,” the corporal at the boy’s right ear said.

The pressure popped. Something wet and hot burned down his ankle. The boy pushed his heels into the ground with a yowl, arching his back. He clenched his fingers and teeth even as the corporals held him down.

“Look at all that pus.”

“It is a good thing we caught it when we did.”

“Somebody should clean that.”

“What is taking the lieutenant?” The general stood up.

The pain only got worse, especially now the heavy iron was gone. For a moment Kemdin felt as if his feet would fly into the air without anything to hold him down. However, the corporals held him too tight for him to do more than stare at the lesions.

The smithy grunted. “Well, I guess we ought to prep the brand first than start with new irons. Those wounds are pretty nasty.”

“Conceded,” the general said, turning towards the door. “Where did that lieutenant go?”

“Con-what?”

The smithy rose, fumbling to put the all-key back on the ring. Kemdin’s eyes turned to it, wishing for more than anything—no—begging the four gods to let him have that key.

And it fell.

Kemdin watched it drop. His eyes followed it as it landed in a small pile of soot on the ground, not making the slightest of sounds under the bickering of the general and the smithy.

“It means I agree.” The general was already growing irritated with the lack of intelligence in this smithy.

Scooting his foot with a flinch of pain, the boy kicked soot onto the key. It was almost covered. No one noticed, expecting he was writhing from the pain. He twisted his back again, scuffing in the dirty ash on the floor once more. This time the key was buried completely.

Stumping over to the wall, the smithy grabbed an iron poker. It had the initials for Traitor’s Son. He stuck it into the hot part of the fire and turned it, humming to himself

Comments (0)