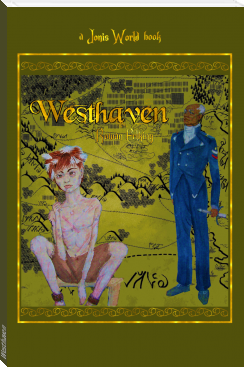

Westhaven, Rowan Erlking [large ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Rowan Erlking

Book online «Westhaven, Rowan Erlking [large ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Rowan Erlking

“Shouldn’t we numb his skin first?” a corporal asked, glancing at the boy’s bare shoulder where there were already lacerations from whipping.

“And how do we propose we do that?” the smithy said with bite.

“Ice?” one of them suggested.

“Clove oil,” another said.

“That’s witchcraft!” The smithy unexpectedly shouted, jumping up.

The general turned to look back, interested. Though, most of the bickering ended with the sudden return of the lieutenant whose boots tromped back at a jog over the stone and dirt on the floor.

“Sorry I took so long.” The lieutenant marched into the smith shop with a woman right behind him. She was carrying a steaming bucket of water. “But we had to get the water to—holy…. It’s worse than I thought.”

Turning his head to see the lieutenant while the soldier gestured for the woman to set down the bucket at the slave’s feet, the boy panted hard, feeling the beginnings of a fever. Gently lifting his feet into the hot steamy water, the woman immediately started to clean the wounds, wiping with a soft rag. It stung his skin and caused his flesh to bleed more.

“What is in that water?” the general asked.

“Certain herbs and salt,” the woman said.

Kemdin looked at her face. She was human. She smiled at him.

“What herbs? Clove oil?” the general asked.

She blinked at him, her smile falling as their eyes met. Her neck stiffened when she answered the general. “Yes. It reduces the pain. There is also yarrow for his wounds, and golden seal to reduce inflammation, rose water to help against bruising, and witch hazel for the same thing. The salt is an antiseptic.”

“Is there a spell with this herbal treatment?” the general asked, his voice almost threatening.

Already Kemdin tightened his arms to his body waiting for a blow. It really was best if General Winstrong did not know that the people of Kalsworth used herbal magic.

“No need,” the woman replied. “These herbs naturally heal.”

“How quickly?” the general asked.

The boy clenched his eyes shut.

But the woman had begun to brush her hands over his wound again with the water. “I’m afraid wounds like this will take several months to truly heal. After I wash them, I will have to bind them with bruised comfrey leaves.”

“Why leaves in with the bandages?” The general’s voice sounded as if he were a snake that would bite any second.

Sounding calm, though her fingers trembled as she stroked the boy’s swollen ankles, the woman said, “Comfrey naturally helps heal wounds. Of course that infected spot there on his right foot ought not to touch the plant. It is only for smaller lesions.”

She then continued to clean the boy’s wounds, pulling his feet deeper into the tub. She whispered, “Let them soak for a while.”

“And what makes you qualified to treat wounds?” the general asked, still sounding angry.

The woman rose.

The boy could hear her feet on the ground. However, his mind immediately went back to that key, and he opened his eyes to look for it. The dust pile was gone, scooted as if the bucket had been set on it and shoved to the bench. How could he get to it now? Turning his head, sweat rolled down. He breathed in hard.

But there he came face to face with the lieutenant.

A flash of horror went through him. If that lieutenant touched him then he would know about the key. The corporals’ gifts were not as strong as the lieutenant’s. They could only feel emotion of those they touched, and his feelings of fear and hope could be easily misinterpreted. But if the lieutenant touched him, that would be the end of it.

Lowering his eyes to the water, Kemdin turned his thoughts from the key to the pain of his ankles. He had to think about the pain and nothing else. One thing he had learned from being among the Sky Children was that when the soldiers stole thoughts from their victims, the surface thoughts always came first. Pain and emotion jumped out at them like a rock, blindsiding them with enough oomph that it gave their victims a momentary opportunity to escape. So, pain. He had to focus on the pain.

And there was plenty of pain to think of. His ankles throbbed. The blood flow even colored the water though it was slowing down. The salt stung his skin, and the entire right side of his right foot hurt as if an animal had taken a bite out of it. Only the relief of the pressure being gone was left.

“I am a mother,” the woman had said, her voice speaking over the boy’s head with a familiar ring. “And as a mother, I know how to care for children.”

“You’re not a witch?” the general said.

She gave an amused smile. “A witch? If I were a witch, I could cure that boy in one day.”

The corporals holding the boy gasped. They stared up at her.

The lieutenant stood up. “In a day? Are you serious?”

“Do not entertain the thought,” General Winstrong said, glaring threateningly at his men. “Witchcraft is dangerous.”

“It is,” the woman said then glanced toward the smithy. “Which is why we don’t— What is he doing?”

She walked over to the fire.

“Heating the iron,” the general said casually.

The smithy lifted the branding iron up. The tip glowed red. “We’re going to mark a Traitor’s Son.”

The woman took a step back. Her eyes rested on the iron, then the boy, then the lieutenant, and then the water the boy was soaking his wounds in. “A traitor’s son? You got me here to heal a traitor’s son?”

“My servant,” the general said, gesturing to his corporals. “And I need you men to hold him so the mark does not slide.”

The corporals nodded back. They held the boy tighter, though sweat dribbled down so thickly that his hair was now damp.

Backing towards the far wall, the woman retreated as if horrified.

Placing one hand on the water tub in case Kemdin accidentally kicked it over, the lieutenant waited for the smithy. The man approached, lowering the iron to the boy’s right shoulder.

The burning was the same as he had remembered. Awful. Hot. And so terrible, that it invoked every horrible memory from that day when his father was killed by the general. Kemdin howled. Tears rolled down his cheeks. He tried to pull from the scorching. But there was no relief, even after they lifted the iron off. His eyes closed, panting hard, he could still see his father lying there among the familiar smells of the smith shop.

“How long should we wait before I can put on the leg irons?” the smithy’s voice echoed distantly over Kemdin’s head. The man tossed the branding tip back into the fire to burn off the charred skin that had stuck to it.

The general looked to the lieutenant. The lieutenant glanced back at the woman.

“How long?”

Her face wrinkled with distasteful look at Kemdin. “I don’t care. He’s a traitor’s son. You can stop now.”

“But I don’t want him crippled,” General Winstrong said huffing in the way he did when was worn from someone’s presence. “I need him to be able to walk for errands. How long?”

Walking to the door, she shook her head. “I said I don’t care. Just wrap up his legs and keep him off his feet for at least a week.”

“Would that delay us from putting on irons?” the smithy asked already walking to the hanging chains and ankle cuffs.

The corporals peered at the boy. He stared at the ceiling, glassy-eyed from shock. His branded skin smoked. One of them let go and whispered into the lieutenant’s ear.

Peering down at the tub of water, the lieutenant shrugged. He then crouched down, dipping his hands into the liquid and herbs then shrugged again. “I think maybe we can wrap them now with those leaves. She had brought them already. Then doubly wrap them for protection while we put on the irons.”

“But the irons better not be too loose,” the general snapped irritably.

“No worries about that.” The smithy said, tugging on one of the chains on the wall. “We fit the irons now to make sure of the size, then wrap his feet. Then we put them on and weld them shut.”

“But then how do we get the bandages off when he’s healed?” a corporal asked.

“They’ll fall off,” the smithy said.

“We’ll cut them off,” the lieutenant answered, casting the smithy a dirty look.

The corporals shrugged as they turned, bracing the boy in case he moved.

The woman had long gone as the general gestured for the lieutenant to put on the first wrapping. Lifting Kemdin’s feet from the water, the lieutenant gently dried them. He took up the bandages and the leaves the woman had left then scooted the water bucket to the side. The key still did not show up, despite how Kemdin had kept his eye out for it.

And though he tried to keep awake, Kemdin was now feverish, going in and out of consciousness as the blue-eye wrapped his foot with a thin layer of gauze. He hardly felt the smith sizing the leg irons for his future growth as well as for the size of his feet so they would not come off from being too big. Only when the soldiers touched his ankle, wrapping it again, did he come to because of the pressure and pain. Then he saw the hot metal the smithy had dipped one end of the open leg iron in.

“No!” Kemdin shouted out, kicking to get free.

The corporals shoved him down, holding him tight. The lieutenant and the other corporal grabbed that leg to hold it still.

Watching the hot leg iron carried with tongs go around his wrapped ankle, Kemdin braced himself for the worst pain yet.

It seared all the way around. But then the smithy immediately shoved the boy’s foot and ankle into the treated water.

The oil in it caught fire.

“You stupid!” The lieutenant shouted, rising up. “There’s oil in that!”

“Get some water then!” The smithy shouted after him, throwing dirt onto the flames that burned the edge of the boy’s breeches and his bandages.

Running over to the hand pump in the corner, the lieutenant grabbed the nearest pot and pumped hard. He filled it only just before dashing back and dousing the boy’s entire leg.

The fire was out. Every one of them stared at the burned remains of boy’s skin.

“I think we need more bandages,” one of the corporals murmured.

The others nodded, agreeing.

The second iron was wrapped around the boy’s ankle without incident, dunked to cool in pure water. And though they treated and wrapped his burned leg with the ointment and bandages from the kit the lieutenant had brought with the woman, Kemdin was feverish and shaking when they were done.

“I suppose we ought to take him to a doctor,” the lieutenant murmured.

“And do what?” the general asking, glaring hard at him.

With a shrug, the lieutenant said, “I don’t know. Give him something to drink to help him recover?”

“It’s just shock,” the general said. “There is no way to treat it that I know of.”

“And what if he dies?” the lieutenant asked.

They had set Kemdin on the bench where he lay, trembling, with his eyes closed. Sweat still poured off his forehead, and his face was flushed. The corporals peered at him, wondering the same as the lieutenant.

“I’ll still get paid,” the smithy said.

The general cast him a dark look.

“I performed the service,” the smithy said. “I can’t be blamed for his poor constitution.”

Turning, the general delved into his coin pouch and took out the cost in gold. He dropped it into the swift outstretched hand of the smithy. Then turning again without a word, the general walked over to the boy as he said to the lieutenant, “If he dies I’ll just have to get a new boy. But what a pity to lose this one. He was starting to come along as useful.”

Agreeing, the lieutenant sighed. He waved for the corporals to lift Kemdin off the bench. “Let’s

Comments (0)