ORANGE MESSIAHS, Scott A. Sonders [reading books for 6 year olds .TXT] 📗

- Author: Scott A. Sonders

Book online «ORANGE MESSIAHS, Scott A. Sonders [reading books for 6 year olds .TXT] 📗». Author Scott A. Sonders

ORANGE MESSIAHS

Scott Alixander Sonders

C O N T E N T S

I. PROLOGUE .............….......... 3

1. Natives ............…..…...…......9

2. Killing Lions ...….........…..….. 16

3. Juarez ................….....…... 29

4. The Parker Effect …....….....…….. 55

5. By The Skin Of A Whale …...….…... 79

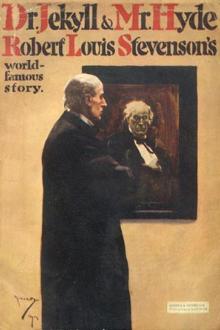

6. Hyde And Sikh .........……..…..….. 102

7. Life After Drowning ............… 114

ii. Epilogue ........................... 136

© 2003 by SAS

PROLOGUE: Winter, 1992

(as told by Catherine Nicholas to Travis W.)

A

stranger’s face can make you feel a thousand things. It can remind you of an enjoyable dream or the perspiration from a nightmare. It can catapult you into a moment of rapture or park you on a memory lane that’s now dry, rutted and lost. A stranger’s face can cause you to shrink in terror and cross the street to get out of the way. Or, it can make you fall in love in less than a heartbeat.

When Travis W. sat next to me in class tonight, my thighs began shaking so hard that I thought the people around me would notice. Staring at his face, when I thought he wouldn’t notice, made me think about forbidden sex and having babies. It was scary. But I wanted to talk to him, to bring him into my fantasy, to let him know my entire history, to take him home and have him touch me where no one had ever touched me. But I just sat there. Mute.

I have an excuse. I’m diagnosed with more dysfunctions than Freud had detractors. Attention deficit, panic and sleep disorders. I believe that one of these mental malfunctions will eventually rupture, break down, someday kill me. Sleeping, a natural endowment for all vertebrates, is for me something illusive.

That’s why I hate cats. They sleep and nap and nap and sleep, while my insomnia is worse than ever. When others are in sandman land, my mind churns like a plutonium driven locomotive, like the dogs of Hell chasing the damned.

But there is an upside. Insomnia gives me a motive to write. No, that’s bullshit. It’s more than a “motive.” It’s an obligation. I cannot not write. That’s how Travis came to be sitting next to me tonight. It was the first meeting of our screenwriting workshop. But now it’s 4 A.M. and I hope to God I fall asleep before the sun comes up. That’s my deadline. I’m genetically part vampire. When I feel the light begin to bleed through my east window, I start to panic. My brain is like the one that Marty Feldman steals in Young Frankenstein: “Abby Normal.” And it’s that abnormal brain that causes a sunrise to rip through my dilated pupils like cataract surgery, the eyelids glued open by atropine. Panic engulfs me like quicksand. I can’t breathe. My heart pounds. Blood swells in my temples. It feels like I’m falling into a huge vortex, falling toward death. My overloaded thoughts become an open can of kerosene, kissed by a carelessly tossed cigarette.

Damn you, Travis. I’d forgotten for awhile how my crazy father would slap my mother for speaking her native tongue. What he did to my mother he did to me. And to Gabriella, the only sibling young enough to grow up with me. My oldest sister, Ramona, who is actually only my half-sister, was already twenty when I was born.

Gabriella, also my half-sister, was ten. She still has strap scars across her back. I’ve learned very few words in Spanish, but I think Gabriella has simply forgotten how to speak. The ability is caged, like a sleeping tiger in her memory. Once awakened, no one knows what the claws will catch.

“We’re in America now,” my Russian father would tell my mother. “In America, we speak American.” He always seemed to forget that he only got his green card because of mother.

She’d already been here twenty years. All of her children were born in America. If anyone didn’t speak “American,” it was my father. To this day, he speaks English like a cartoon character, like Boris Badenoff in Rocky And Bullwinkle.

My bet is that he suffers from a neurochemical imbalance. But with his paranoia, he also believes that all psychiatrists are nuts, so he’d never go to one for help. Whatever the reason, he idolized me until I was five, then he just stopped. Cold turkey. Like I was a bad habit he needed to quit. He claimed I was the bastard daughter of my mother’s blonde gynecologist. And later, he claimed that I was the reason my mother divorced him. It’s odd how the truth, even at its most obvious, manages to elude the deluded.

He never for a moment considered that he was less than the ideal husband. He imagined himself as the perfect father. It was outside of his consideration that my mother left him because she had become too full of fury. He was a fool. The fury had become compressed into a small knot in her bowels. It became a tumor. Misshapen, black. Sucking the life from her body. And finally, when the cancer transmuted from benign to malignant, she could no longer continue to forgive him.

As for my father, well, he was what my friends at Alanon call a “rage-aholic.” His own anger blinded him to the fact that my mother could no longer absolve herself for loving him, or letting him destroy her children.

It was her or him. She tried to fight back, once with a fire iron. It put him in the hospital overnight. Twenty-eight stitches across his left shoulder. If she hadn’t left him, one or the other would be dead now. Either way, Gabby still can’t speak.

And now I look like what my father made no secret of wanting, the ultimate WASP. I have the same face and figure of my mother at twenty combined with my father’s coloring. In small ways like this I’m lucky. My mother was a real knockout. I shouldn’t say “was.” At fifty-eight she’s still thin, strong, attractive and elegant looking. But I’ve seen the photographs she keeps stashed in an old hatbox. At twenty, she could have been a beauty queen.

As far as my appearances go, this conjunction of parents’ genetics makes most men trip over their tongues trying to get to me. But on the inside, on the inside I’m damaged goods, a Jekyll and Hyde, deformed and crippled, another ugly duckling waiting for the seasons to change, waiting to grow white feathers and fly away as a beautiful swan.

A swan. A lovely white swan dancing across the stage in Swan Lake. That’s what I’d like to be. Just like in the ballet. The only drawback to this daydream is that my father would like the same thing for me. It’s a Russian thing. A bias toward Tchaikovsky, the Russian composer. My father’s actual surname is “Podlubnyj,” but he fabricated an Anglicized designation.

That’s how I wound up with a label recycled from Russian czars and a Macedonian conqueror, Catherine Alexandra Nicholas. But my mother had a secret revenge, a moment of quiet rebellion. On my birth certificate, she wrote in an additional middle name: Mariella, in remembrance of her own Mexican mother, in remembrance of the heritage that my father had made taboo.

And I use that name everywhere and with everyone, except in front of my father. But one day I will wear my name like a medal, like a Purple Heart. I will thrust it in my father’s face like a badge of honor. I am going to write the story of my family. I know all their histories. I have listened to my mother’s chronicle. I know the credentials of every river she has crossed. And I have listened to my sister, Ramona. I trust her like I would trust the God who she and my mother worship.

“Travis” told me in class today that he believes “the sins of the fathers are washed on the souls of the children.” And I’ve often wondered if there is some kind of purpose and predetermination to what often feels like a facade of life but not life itself. It is as if we are players auditioning for parts in some cinema verité, as if history is merely an endless loop video, as if history and DNA are intertwined, a microscopic helix simulating the macrocosmic chain.

So the story I will tell is either from a plan beyond our reach and consciousness, or one of extraordinary coincidences. It is either a story of commonplace happenstance, or a story of spectacular warning.

It is only by writing it down, changing my clothes, wearing disguises, and then stepping back and reading it as if I were a stranger that I can gain any perspective. By writing it down I may find a glimpse of the really real.

I’m lucky in this task, I have more than my own untrustworthy memories. And memory is untrustworthy. It is a thin line that divides the madwoman from the saint.

The reader’s speculation about a text is often no more or less accurate than the writer’s intention. But as the writer, I am permitted some indiscretion. It is not only my job to record facts, but also my obligation to create reality.

In this creation of reality, and also as a writer, I’ve become familiar with many characters: those I’ve lived, those I’ve dreamed, and those that have emerged from my pen and ink. The “thin line” between living, writing, and dreaming often dissolves into a blur.

History and autobiography invariably reshape themselves into creative fictions, edited by unreliable witnesses with conscious and unconscious agendas. But as I’ve said, I’m more fortunate in this regard because I have evidence that reaches beyond the mere tricks of my own retrospection. With this evidence I will resurrect the bones of these stories from their otherwise eventual ash. The peculiar personalities that will inhabit these now blank pages will rise like the phoenix, spraying dust in the eyes of the reader. And it is only by recording all of these stories that any sense will be made of the strangeness.

I have collected the poetry and stories that my mother, Carla Maria Batista, has carefully typed, labeled and filed, along with assorted newspaper clippings and family photographs, into a series of shoeboxes. I will reconstruct her story and tell it as if I were there. Forgive me for that but it feels so very real to me.

Ramona has supplied me with her journals. She has advised me to read them and keep them safe. She has given me permission to do that what she would never do herself. She has given me permission to make her confessions public.

I have gone on what feels like a pilgrimage to meet Raymond Parker, the father of Ramona and Gabriella. He is the husband that my mother never forgot, even while she embraced my own father. I will tell what Ray Parker never told. I will let him testify on his own behalf, or condemn himself with his own narrative.

I will tell of the legends that have grown around Carlos, like ivy on a statue. I was too young to have known him but I have spoken to his lovers and friends, and even some of his enemies. I have listened

Comments (0)