Tedric, E. E. Smith [reader novel .txt] 📗

- Author: E. E. Smith

Book online «Tedric, E. E. Smith [reader novel .txt] 📗». Author E. E. Smith

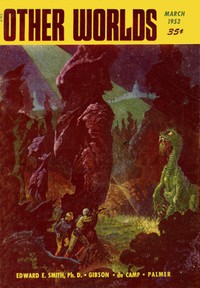

By E. E. SMITH, Ph. D.

Illustrated by J. Allen St. John

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Other Worlds March 1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Aided by Llosir, his strange, new god, Tedric enters into battle with Sarpedion, the sacrifice-demanding god of Lomarr in this story of science and swash-buckling adventure which marks the return of "Doc" Smith, author of the Skylark series, Lensman series, etc.

"The critical point in time of mankind's whole existence is there—RIGHT THERE!" Prime Physicist Skandos slashed his red pencil across the black trace of the chronoviagram. "WHY must man be so stupid? Anyone with three brain cells working should know that for the strength of an individual he should be fed; not bled; that for the strength of a race its virgins should be bred, not sacrificed to propitiate figmental deities. And it would be so easy to straighten things out—nowhere in all reachable time does any other one man occupy such a tremendously—such a uniquely—key-stone position!"

"Easy, yes," his assistant Furmin agreed. "It is a shame to let Tedric die with not one of his tremendous potentialities realized. It would be easy and simple to have him discover carburization and the necessary techniques of heat-treating. That freak meteorite need not lie there unsmelted for another seventy years. However, simple carburization was not actually discovered until two generations later, by another smith in another nation; and you know, Skandos, that there can be no such thing as a minor interference with the physical events of the past. Any such, however small-seeming, is bound to be catastrophically major."

"I know that." Skandos scowled blackly. "We don't know enough about time. We don't know what would happen. We have known how to do it for a hundred years, but have been afraid to act because in all that time no progress whatever has been made on the theory."

He paused, then went on savagely: "But which is better, to have our entire time-track snapped painlessly out of existence—if the extremists are right—or to sit helplessly on our fat rumps wringing our hands while we watch civilization build up to its own total destruction by lithium-tritiide bombs? Look at the slope of that curve—ultimate catastrophe is only one hundred eighty seven years away!"

"But the Council would not permit it. Nor would the School."

"I know that, too. That is why I am not going to ask them. Instead, I am asking you. We two know more of time than any others. Over the years I have found your judgment good. With your approval I will act now. Without it, we will continue our futile testing—number eight hundred eleven is running now, I believe?—and our aimless drifting."

"You are throwing the entire weight of such a decision on me?"

"In one sense, yes. In another, only half, since I have already decided."

"Go ahead."

"So be it."

"Tedric, awaken!"

The Lomarrian ironmaster woke up; not gradually and partially, like one of our soft modern urbanites, but instantaneously and completely, as does the mountain wild-cat. At one instant he lay, completely relaxed, sound asleep; at the next he had sprung out of bed, seized his sword and leaped half-way across the room. Head thrown back, hard blue eyes keenly alert, sword-arm rock-steady he stood there, poised and ready. Beautifully poised, upon the balls of both feet; supremely ready to throw into action every inch of his six-feet-four, every pound of his two-hundred-plus of hard meat, gristle, and bone. So standing, the smith stared motionlessly at the shimmering, almost invisible thing hanging motionless in the air of his room, and at its equally tenuous occupant.

"I approve of you, Tedric." The thing—apparition—whatever it was—did not speak, and the Lomarrian did not hear; the words formed themselves in the innermost depths of his brain. "While you perhaps are a little frightened, you are and have been completely in control. Any other man of your nation—yes, of your world—would have been scared out of what few wits he has."

"You are not one of ours, Lord." Tedric went to one knee. He knew, of course, that gods and devils existed; and, while this was the first time that a god had sought him out personally, he had heard of such happenings all his life. Since the god hadn't killed him instantly, he probably didn't intend to—right away, at least. Hence: "No god of Lomarr approves of me. Also, our gods are solid and heavy. What do you want of me, strange god?"

"I'm not a god. If you could get through this grill, you could cut off my head with your sword and I would die."

"Of course. So would Sar ..." Tedric broke off in the middle of the word.

"I see. It is dangerous to talk?"

"Very. Even though a man is alone, the gods and hence the priests who serve them have power to hear. Then the man lies on the green rock and loses his brain, liver, and heart."

"You will not be overheard. I have power enough to see to that."

Tedric remained silent.

"I understand your doubt. Think, then; that will do just as well. What is it that you are trying to do?"

"I wonder how I can hear when there is no sound, but men cannot understand the powers of gods. I am trying to find or make a metal that is very hard, but not brittle. Copper is no good, I cannot harden it enough. My soft irons are too soft, my hard irons are too brittle; my in-betweens and the melts to which I added various flavorings have all been either too soft or too brittle, or both."

"I gathered that such was your problem. Your wrought iron is beautiful stuff; so is your white cast iron; and you would not, ordinarily, in your lifetime, come to know anything of either carburization or high-alloy steel, to say nothing of both. I know exactly what you want, and I can show you exactly how to make it."

"You can, Lord?" The smith's eyes flamed. "And you will?"

"That is why I have come to you, but whether or not I will teach you depends on certain matters which I have not been able entirely to clarify. What do you want it for—that is, what, basically, is your aim?"

"Our greatest god, Sarpedion, is wrong and I intend to kill him." Tedric's eyes flamed more savagely, his terrifically muscled body tensed.

"Wrong? In what way?"

"In every way!" In the intensity of his emotion the smith spoke aloud. "What good is a god who only kills and injures? What a nation needs, Lord, is people—people working together and not afraid. How can we of Lomarr ever attain comfort and happiness if more die each year than are born? We are too few. All of us—except the priests, of course—must work unendingly to obtain only the necessities of life."

"This bears out my findings. If you make high-alloy steel, exactly what will you do with it?"

"If you give me the god-metal, Lord, I will make of it a sword and armor—a sword sharp enough and strong enough to cut through copper or iron without damage; armor strong enough so that swords of copper or iron cannot cut through it. They must be so because I will have to cut my way alone through a throng of armed and armored mercenaries and priests."

"Alone? Why?"

"Because I cannot call in help; cannot let anyone know my goal. Any such would lie on the green stone very soon. They suspect me; perhaps they know. I am, however, the best smith in all Lomarr, hence they have slain me not. Nor will they, until I have found what I seek. Nor then, if by the favor of the gods—or by your favor, Lord—the metal be good enough."

"It will be, but there's a lot more to fighting a platoon of soldiers than armor and a sword, my optimistic young savage."

"That the metal be of proof is all I ask, Lord," the smith insisted, stubbornly. "The rest of it lies in my care."

"So be it. And then?"

"Sarpedion's image, as you must already know, is made of stone, wood, copper, and gold—besides the jewels, of course. I take his brain, liver, and heart; flood them with oil, and sacrifice them ..."

"Just a minute! Sarpedion is not alive and never has been; does not, as a matter of fact, exist. You just said, yourself, that his image was made of stone and copper and ..."

"Don't be silly, Lord. Or art testing me? Gods are spirits; bound to their images, and in a weaker way to their priests, by linkages of spirit force. Life force, it could be called. When those links are broken, by fire and sacrifice, the god may not exactly die, but he can do no more of harm until his priests have made a new image and spent much time and effort in building up new linkages. One point now settled was bothering me; what god to sacrifice him to. I'll make an image for you to inhabit, Lord, and sacrifice him to you, my strange new god. You will be my only god as long as I live. What is your name, Lord? I can't keep on calling you 'strange god' forever."

"My name is Skandos."

"S ... Sek ... That word rides ill on the tongue. With your permission, Lord, I will call you Llosir."

"Call me anything you like, except a god. I am not a god."

"You are being ridiculous, Lord Llosir," Tedric chided. "What a man sees with his eyes, hears with his ears—especially what a man hears without ears, as I hear now—he knows with certain knowledge to be the truth. No mere man could possibly do what you have done, to say naught of what you are about to do."

"Perhaps not an ordinary man of your ..." Skandos almost said "time," but caught himself "... of your culture, but I am ordinary enough and mortal enough in my own."

"Well, that could be said of all gods, everywhere." The smith's mien was quiet and unperturbed; his thought was loaded to saturation with unshakable conviction.

Skandos gave up. He could argue for a week, he knew, without making any impression whatever upon what the stubborn, hard-headed Tedric knew so unalterably to be the truth.

"But just one thing, Lord," Tedric went on with scarcely a break. "Have I made it clear that I intend to stop human sacrifice? That there is to be no more of it, even to you? We will offer you anything else—anything else—but not even your refusal to give me the god-metal will change my stand on that."

"Good! See to it that nothing ever does change it. As to offerings or sacrifices, there are to be none, of any kind. I do not need, I do not want, I will not have any such. That is final. Act accordingly."

"Yes, Lord. Sarpedion is a great and powerful god, but art sure that his sacrifice alone will establish linkages strong enough to last for all time?"

Skandos almost started to argue again, but checked himself. After all, the proposed sacrifice was necessary for Tedric and his race, and it would do no harm.

"Sarpedion will be enough. And as for the image, that isn't necessary, either."

"Art wrong, Lord. Without image and temple, everyone would think you a small, weak god, which thought can never be. Besides, the image might make it easier for me to call on you in time of need."

"You can't call me. Even if I could receive your call, which is very doubtful, I wouldn't answer it. If you ever see me or hear from me again, it will be because I wish it, not you." Skandos intended this for a clincher, but it didn't turn out that way.

"Wonderful!" Tedric exclaimed. "All gods act that way, in spite of what they—through their priests—say. I am overwhelmingly glad that you are being honest with me. Hast found me worthy of the god-metal, Lord Llosir?"

"Yes, so let's get at it. Take that biggest chunk of 'metal-which-fell-from-the-sky'—you'll find it's about twice your weight ..."

"But I have never been able to work that particular piece of metal, Lord."

"I'm not surprised. Ordinary meteorites are nickel-iron, but this one carries two additional and highly unusual elements, tungsten and vanadium, which are necessary for our purpose. To melt it you'll have to run your fires a lot hotter. You'll also have to have a carburizing pot and willow charcoal and metallurgical coke and several other things. We'll go into details later. That green stone from which altars are made—you can secure some of it?"

"Any amount of it."

"Of it take your full weight. And of the black ore of which you have occasionally used

Comments (0)