The God in the Box, Sewell Peaslee Wright [motivational books for women TXT] 📗

- Author: Sewell Peaslee Wright

Book online «The God in the Box, Sewell Peaslee Wright [motivational books for women TXT] 📗». Author Sewell Peaslee Wright

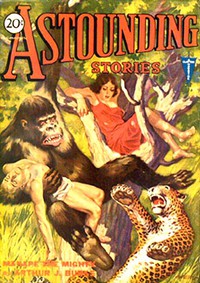

Transcriber's Note: This e-text was produced from Astounding Stories, September, 1931. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

"A little object lesson, as it were!"

The God in the Box

By Sewell Peaslee Wright

In the course of his Special Patrol duties Commander John Hanson resolves the unique and poignant mystery of "toma annerson."

This is a story I never intended to tell. I would not even tell it now if it were not for the Zenians.

Understand that I do not dislike the Zenians. One of the best officers I ever had was a Zenian. His name was Eitel, and he served under me on the old Tamon, my first command. But lately the Zenians have made rather too much of the exploits of Ame Baove.

The history of the Universe gives him credit, and justly, for making the first successful exploration in space. Baove's log of that trip is a classic that every school-child knows.

But I have a number of friends who are natives of Zenia, and they fret me with their boastings.

"Well, Hanson," they say, "your Special Patrol Service has done wonderful work, largely under the officership of Earth-men. But after all, you have to admit that it was a Zenian who first mastered space!"

Perhaps it is just fractiousness of an old man, but countless repetitions of such statements, in one form or another, have irritated me to the point of action—and before going further, let me say, for the benefit of my Zenian friends, that if they care to dig deeply enough into the archives, somewhere they will find a brief report of these adventures recorded in the log of one of my old ships, the Ertak, now scrapped and forgotten. Except, perhaps, by some few like myself, who knew and loved her when she was one of the newest and finest ships of the Service.

I commanded the Ertak during practically her entire active life. Those were the days when John Hanson was not an old man, writing of brave deeds, but a youngster of half a century, or thereabouts, and full of spirit. Sometimes, when memory brings back those old days, it seems hard for me to believe that John Hanson, Commander of the Ertak, and old John Hanson, retired, and a spinner of ancient yarns, are one and the same—but I must get on to my story, for youth is impatient, and from "old man" to "old fool" is a short leap for a youthful mind.

The Special Patrol Service is not all high adventure. It was not so even in the days of the Ertak. There was much routine patrolling, and the Ertak drew her full share of this type of duty. We hated it, of course, but in that Service you do what you are told and say nothing.

We were on a routine patrol, with only one possible source of interest in our orders. The wizened and sour-faced scientists the Universe acclaims so highly had figured out that a certain planet, thus far unvisited, would be passing close to the line of our patrol, and our orders read, "if feasible," to inspect this body, and if inhabited, which was doubted, to make contact.

There was a separate report, if I remember correctly, with a lot of figures. This world was not large; smaller than Earth, as a matter of fact, and its orbit brought it into conjunction with our system only once in some immemorable period of time. I suppose that record is stored away, too, if anybody is interested in it. It was largely composed of guesses, and most of them were wrong. These white-coated scientists do a lot of wild guessing, if the facts were known.

However, she did show up at about the place they had predicted. Kincaide, my second officer, was on duty when the television disk first picked her up, and he called me promptly.

"Strobus"—that was the name the scientists had given this planet we were to look over—"Strobus is in view, sir, if you'd like to look her over," he reported. "Not close enough yet to determine anything of interest, however, even with maximum power."

I considered for a moment, scowling at the microphone.

"Very well, Mr. Kincaide," I said at length. "Set a course for her. We'll give her a glance, anyway."

"Yes, sir," replied Kincaide promptly. One of the best officers in the Service, Kincaide. Level-headed, and a straight thinker. He was a man for any emergency. I remember—but I've already told that story.

I turned back to my reports, and forgot all about this wandering Strobus. Then I turned in, to catch up somewhat on my sleep, for we had had some close calls in a field of meteors, and the memory of a previous disaster was still fresh in my mind.1 I had spent my "watch below" in the navigating room, and now I needed sleep rather badly. If the scientists really want to do something for humanity, why don't they show us how to do without food and sleep?

When, refreshed and ready for anything, I did report to the navigating room, Correy, my first officer, was on duty.

"Good morning, sir," he nodded. It was the custom, on ships I commanded, for the officers to govern themselves by Earth standards of time; we created an artificial day and night, and disregarded entirely, except in our official records, the enar and other units of the Universal time system.

"Good morning, Mr. Correy. How are we bearing?"

"Straight for our objective, sir." He glanced down at the two glowing charts that pictured our surroundings in three dimensions, to reassure himself. "She's dead ahead, and looming up quite sizeably."

"Right!" I bent over the great hooded television disk—the ponderous type we used in those days—and picked up Strobus without difficulty. The body more than filled the disk and I reduced the magnification until I could get a full view of the entire exposed surface.

Strobus, it seemed, bore a slight resemblance to one view of my own Earth. There were two very apparent polar caps, and two continents, barely connected, the two of them resembling the numeral eight in the writing of Earth-men; a numeral consisting of two circles, one above the other, and just touching. One of the roughly circular continents was much larger than the other.

"Mr. Kincaide reported that the portions he inspected consisted entirely of fluid sir," commented Correy. "The two continents now visible have just come into view, so I presume that there are no others, unless they are concealed by the polar caps. Do you find any indications of habitation?"

"I haven't examined her closely under high magnification," I replied. "There are some signs...."

I increased power, and began slowly searching the terrain of the distant body. I had not far to search before I found what I sought.

"We're in luck, Mr. Correy!" I exclaimed. "Our friend is inhabited. There is at least one sizeable city on the larger continent and ... yes, there's another! Something to break the monotony, eh? Strobus is an 'unknown' on the charts."

"Suppose we'll have trouble, sir?" asked Correy hopefully. Correy was a prime hand for a fight of any kind. A bit too hot-headed perhaps, but a man who never knew when he was beaten.

"I hope not; you know how they rant at the Base when we have to protect ourselves," I replied, not without a certain amount of bitterness. "They'd like to pacify the Universe with never a sweep of a disintegrator beam. 'Of course, Commander Hanson' some silver-sleeve will say, 'if it was absolutely vital to protect your men and your ship'—ugh! They ought to turn out for a tour of duty once in a while, and see what conditions are." I was young then, and the attitude of my conservative superiors at the Base was not at all in keeping with my own views, at times.

"You think, then, that we will have trouble, sir?"

"Your guess is as good is mine," I shrugged. "The people of this Strobus know nothing of us. They will not know whether we come as friends or enemies. Naturally, they will be suspicious. It is hard to explain the use of the menore, to convey our thoughts to them."

I glanced up at the attraction meter, reflecting upon the estimated mass of the body we were approaching. By night we should be nearing her atmospheric envelope. By morning we should be setting down on her.

"We'll hope for the best, sir," said Correy innocently.

I bent more closely over the television disk, to hide my smile. I knew perfectly what the belligerent Correy meant by "the best."

The next morning, at atmospheric speed, we settled down swiftly over the larger of the two continents, Correy giving orders to the navigating room while I divided my attention between the television disk and the altimeter, with a glance every few seconds at the surface temperature gauge. In unknown atmospheres, it is not difficult to run up a considerable surface temperature, and that is always uncomfortable and sometimes dangerous.

"The largest city seems to be nearer the other continent. You should be able to take over visually before long. Has the report on the atmosphere come through yet?"

"Not yet. Just a moment, sir." Correy spoke for a moment into his microphone and turned to me with a smile.

"Suitable for breathing," he reported. "Slight excess of oxygen, and only a trace of moisture. Hendricks just completed the analysis." Hendricks, my third officer, was as clever as a laboratory man in many ways, and a red-blooded young officer as well. That's a combination you don't come across very often.

"Good! Breathing masks are a nuisance. I believe I'd reduce speed somewhat; she's warming up. The big city I mentioned is dead ahead. Set the Ertak down as close as possible."

"Yes, sir!" snapped Correy, and I leaned over the television disk to examine, at very close range, the great Strobian metropolis we were so swiftly approaching.

The buildings were all tall, and constructed of a shining substance that I could not identify, even though I could now make out the details of their architecture, which was exceedingly simple, and devoid of ornament of any kind, save an occasional pilaster or flying buttress. The streets were broad, and laid out to cut the city into lozenge-shaped sections, instead of the conventional squares. In the center of the city stood a great lozenge-shaped building with a smooth, arched roof. From every section of the city, great swarms of people were flocking in the direction of the spot toward which the Ertak was settling, on foot and in long, slim vehicles of some kind that apparently carried several people.

"Lots of excitement down there, Mr. Correy," I commented. "Better tell Mr. Kincaide to order up all hands, and station a double guard at the port. Have a landing force, armed with atomic pistols and bombs, and equipped with menores, as an escort."

"And the disintegrator-ray generators—you'll have them in operation, sir, just in case?"

"That might be well. But they are not to be used except in the greatest emergency, understand. Hendricks will accompany me, if it seems expeditious to leave the ship, leaving you in command here."

"Very well, sir!" I knew the arrangement didn't suit him, but he was too much the perfect officer to protest, even with a glance. And besides, at the moment, he was very busy with orders to the men in the control room, forward, as he conned the ship to the place he had selected to set her down.

But busy as he was, he did not forget the order to tune up the disintegrator-ray generators.

While the great circular door of the Ertak was backing out ponderously from its threaded seat, suspended by its massive gimbals, I inspected the people of this new world.

My first impression was that they were a soldiery people, for there were no jostling crowds swarming around the ship, such as

Comments (0)