Orphans of the Void, Michael Shaara [books to read in a lifetime .TXT] 📗

- Author: Michael Shaara

Book online «Orphans of the Void, Michael Shaara [books to read in a lifetime .TXT] 📗». Author Michael Shaara

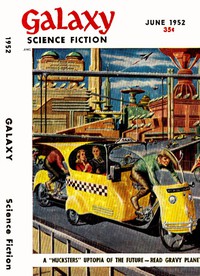

By MICHAEL SHAARA

Illustrated by EMSH

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction June 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Finding a cause worth dying for is no

great trick—the Universe is full of them. Finding

one worth living for is the genuine problem!

In the region of the Coal Sack Nebula, on the dead fourth planet of a star called Tyban, Captain Steffens of the Mapping Command stood counting buildings. Eleven. No, twelve. He wondered if there was any significance in the number. He had no idea.

"What do you make of it?" he asked.

Lieutenant Ball, the executive officer of the ship, almost tried to scratch his head before he remembered that he was wearing a spacesuit.

"Looks like a temporary camp," Ball said. "Very few buildings, and all built out of native materials, the only stuff available. Castaways, maybe?"

Steffens was silent as he walked up onto the rise. The flat weathered stone jutted out of the sand before him.

"No inscriptions," he pointed out.

"They would have been worn away. See the wind grooves? Anyway, there's not another building on the whole damn planet. You wouldn't call it much of a civilization."

"You don't think these are native?"

Ball said he didn't. Steffens nodded.

Standing there and gazing at the stone, Steffens felt the awe of great age. He had a hunch, deep and intuitive, that this was old—too old. He reached out a gloved hand, ran it gently over the smooth stone ridges of the wall. Although the atmosphere was very thin, he noticed that the buildings had no airlocks.

Ball's voice sounded in his helmet: "Want to set up shop, Skipper?"

Steffens paused. "All right, if you think it will do any good."

"You never can tell. Excavation probably won't be much use. These things are on a raised rock foundation, swept clean by the wind. And you can see that the rock itself is native—" he indicated the ledge beneath their feet—"and was cut out a long while back."

"How long?"

Ball toed the sand uncomfortably. "I wouldn't like to say off-hand."

"Make a rough estimate."

Ball looked at the captain, knowing what was in his mind. He smiled wryly and said: "Five thousand years? Ten thousand? I don't know."

Steffens whistled.

Ball pointed again at the wall. "Look at the striations. You can tell from that alone. It would take even a brisk Earth wind at least several thousand years to cut that deep, and the wind here has only a fraction of that force."

The two men stood for a long moment in silence. Man had been in interstellar space for three hundred years and this was the first uncovered evidence of an advanced, space-crossing, alien race. It was an historic moment, but neither of them was thinking about history.

Man had been in space for only three hundred years. Whatever had built these had been in space for thousands of years.

Which ought to give them, thought Steffens uncomfortably, one hell of a good head-start.

While the excav crew worked steadily, turning up nothing, Steffens remained alone among the buildings. Ball came out to him, looked dryly at the walls.

"Well," he said, "whoever they were, we haven't heard from them since."

"No? How can you be sure?" Steffens grunted. "A space-borne race was roaming this part of the Galaxy while men were still pitching spears at each other, that long ago. And this planet is only a parsec from Varius II, a civilization as old as Earth's. Did whoever built these get to Varius? Or did they get to Earth? How can you know?"

He kicked at the sand distractedly. "And most important, where are they now? A race with several thousand years...."

"Fifteen thousand," Ball said. When Steffens looked up, he added: "That's what the geology boys say. Fifteen thousand, at the least."

Steffens turned to stare unhappily at the buildings. When he realized now how really old they were, a sudden thought struck him.

"But why buildings? Why did they have to build in stone, to last? There's something wrong with that. They shouldn't have had a need to build, unless they were castaways. And castaways would have left something behind. The only reason they would need a camp would be—"

"If the ship left and some of them stayed."

Steffens nodded. "But then the ship must have come back. Where did it go?" He ceased kicking at the sand and looked up into the blue-black midday sky. "We'll never know."

"How about the other planets?" Ball asked.

"The report was negative. Inner too hot, outer too heavy and cold. The third planet is the only one with a decent temperature range, but it has a CO2 atmosphere."

"How about moons?"

Steffens shrugged. "We could try them and find out."

The third planet was a blank, gleaming ball until they were in close, and then the blankness resolved into folds and piling clouds and dimly, in places, the surface showed through. The ship went down through the clouds, falling the last few miles on her brakers. They came into the misty gas below, leveled off and moved along the edge of the twilight zone.

The moons of this solar system had yielded nothing. The third planet, a hot, heavy world which had no free oxygen and from which the monitors had detected nothing, was all that was left. Steffens expected nothing, but he had to try.

At a height of several miles, the ship moved up the zone, scanning, moving in the familiar slow spiral of the Mapping Command. Faint dark outlines of bare rocks and hills moved by below.

Steffens turned the screen to full magnification and watched silently.

After a while he saw a city.

The main screen being on, the whole crew saw it. Someone shouted and they stopped to stare, and Steffens was about to call for altitude when he saw that the city was dead.

He looked down on splintered walls that were like cloudy glass pieces rising above a plain, rising in a shattered circle. Near the center of the city, there was a huge, charred hole at least three miles in diameter and very deep. In all the piled rubble, nothing moved.

Steffens went down low to make sure, then brought the ship around and headed out across the main continent into the bright area of the sun. The rocks rolled by below, there was no vegetation at all, and then there were more cities—all with the black depression, the circular stamp that blotted away and fused the buildings into nothing.

No one on the ship had anything to say. None had ever seen a war, for there had not been war on Earth or near it for more than three hundred years.

The ship circled around to the dark side of the planet. When they were down below a mile, the radiation counters began to react. It became apparent, from the dials, that there could be nothing alive.

After a while Ball said: "Well, which do you figure? Did our friends from the fourth planet do this, or were they the same people as these?"

Steffens did not take his eyes from the screen. They were coming around to the daylight side.

"We'll go down and look for the answer," he said. "Break out the radiation suits."

He paused, thinking. If the ones on the fourth planet were alien to this world, they were from outer space, could not have come from one of the other planets here. They had starships and were warlike. Then, thousands of years ago. He began to realize how important it really was that Ball's question be answered.

When the ship had gone very low, looking for a landing site, Steffens was still by the screen. It was Steffens, then, who saw the thing move.

Down far below, it had been a still black shadow, and then it moved. Steffens froze. And he knew, even at that distance, that it was a robot.

Tiny and black, a mass of hanging arms and legs, the thing went gliding down the slope of a hill. Steffens saw it clearly for a full second, saw the dull ball of its head tilt upward as the ship came over, and then the hill was past.

Quickly Steffens called for height. The ship bucked beneath him and blasted straight up; some of the crew went crashing to the deck. Steffens remained by the screen, increasing the magnification as the ship drew away. And he saw another, then two, then a black gliding group, all matched with bunches of hanging arms.

Nothing alive but robots, he thought, robots. He adjusted to full close up as quickly as he could and the picture focused on the screen. Behind him he heard a crewman grunt in amazement.

A band of clear, plasticlike stuff ran round the head—it would be the eye, a band of eye that saw all ways. On the top of the head was a single round spot of the plastic, and the rest was black metal, joined, he realized, with fantastic perfection. The angle of sight was now almost perpendicular. He could see very little of the branching arms of the trunk, but what had been on the screen was enough. They were the most perfect robots he had ever seen.

The ship leveled off. Steffens had no idea what to do; the sudden sight of the moving things had unnerved him. He had already sounded the alert, flicked out the defense screens. Now he had nothing to do. He tried to concentrate on what the League Law would have him do.

The Law was no help. Contact with planet-bound races was forbidden under any circumstances. But could a bunch of robots be called a race? The Law said nothing about robots because Earthmen had none. The building of imaginative robots was expressly forbidden. But at any rate, Steffens thought, he had made contact already.

While Steffens stood by the screen, completely bewildered for the first time in his space career, Lieutenant Ball came up, hobbling slightly. From the bright new bruise on his cheek, Steffens guessed that the sudden climb had caught him unaware. The exec was pale with surprise.

"What were they?" he said blankly. "Lord, they looked like robots!"

"They were."

Ball stared confoundedly at the screen. The things were now a confusion of dots in the mist.

"Almost humanoid," Steffens said, "but not quite."

Ball was slowly absorbing the situation. He turned to gaze inquiringly at Steffens.

"Well, what do we do now?"

Steffens shrugged. "They saw us. We could leave now and let them quite possibly make a ... a legend out of our visit, or we could go down and see if they tie in with the buildings on Tyban IV."

"Can we go down?"

"Legally? I don't know. If they are robots, yes, since robots cannot constitute a race. But there's another possibility." He tapped his fingers on the screen confusedly. "They don't have to be robots at all. They could be the natives."

Ball gulped. "I don't follow you."

"They could be the original inhabitants of this planet—the brains of them, at least, protected in radiation-proof metal. Anyway," he added, "they're the most perfect mechanicals I've ever seen."

Ball shook his head, sat down abruptly. Steffens turned from the screen, strode nervously across the Main Deck, thinking.

The Mapping Command, they called it. Theoretically, all he was supposed to do was make a closeup examination of unexplored systems, checking for the presence of life-forms as well as for the possibilities of human colonization. Make a check and nothing else. But he knew very clearly that if he returned to Sirius base without investigating this robot situation, he could very well be court-martialed one way or the other, either for breaking the Law of Contact or for dereliction of duty.

And there was also the possibility, which abruptly occurred to him, that the robots might well be prepared to blow his ship to hell and gone.

He stopped in the center of the deck. A whole new line of thought opened up. If the robots were armed and ready ... could this be an outpost?

An outpost!

He turned and raced for the bridge. If he went in and landed and was lost, then the League might never know in time. If he went in and stirred up trouble....

The thought in his mind was scattered suddenly, like a mist blown away. A voice was speaking in his mind, a deep calm voice that seemed to say:

"Greetings. Do not be alarmed. We do not wish you to be alarmed. Our desire is only to serve...."

"Greetings, it said! Greetings!" Ball was mumbling

Comments (0)