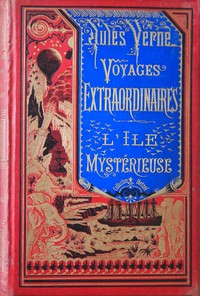

The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [classic novels .txt] 📗

- Author: Jules Verne

Book online «The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [classic novels .txt] 📗». Author Jules Verne

“What is that?”

“Some fire,” replied the sailor, who thought of nothing else.

“We will have it, Pencroff,” said Smith. “But when you were carrying me here yesterday, did not I see a mountain rising in the west?”

“Yes,” saidSpilett, “quite a high one.”

“All right,” exclaimed the engineer. “Tomorrow we will climb to its summit and determine whether this is an island or a continent; until then I repeat there is nothing to do.”

“But there is; we want fire!” cried the obstinate sailor again.

“Have a little patience, Pencroff, and we will have the fire,” said Spilett.

The other looked at the reporter as much as to say, “If there was only you to make it we would never taste roast meat.” But he kept silent.

Smith had not spoken. He seemed little concerned about this question of fire. For some moments he remained absorbed in his own thoughts. Then he spoke as follows:—

“My friends, our situation is, doubtless, deplorable, nevertheless it is very simple. Either we are upon a continent, and, in that case, at the expense of greater or less fatigue, we will reach some inhabited place, or else we are on an island. In the latter case, it is one of two things; if the island is inhabited, we will get out of our difficulty by the help of the inhabitants; if it is deserted, we will get out of it by ourselves.”

“Nothing could be plainer than that,” said Pencroff.

“But,” asked Spilett, “whether it is a continent or an island, whereabouts do you think this storm has thrown us, Cyrus?”

“In truth, I cannot say,” replied the engineer, “but the probability is that we are somewhere in the Pacific. When we left Richmond the wind was northeast, and its very violence proves that its direction did not vary much. Supposing it unchanged, we crossed North and South Carolina, Georgia, the Gulf of Mexico, and the narrow part of Mexico, and a portion of the Pacific Ocean. I do not estimate the distance traversed by the balloon at less than 6,000 or 7,000 miles, and even if the wind had varied a half a quarter it would have carried us either to the Marquesas Islands or to the Low Archipelago; or, if it was stronger than I suppose, as far as New Zealand. If this last hypothesis is correct, our return home will be easy. English or Maoris, we shall always find somebody with whom to speak. If, on the other hand, this coast belongs to some barren island in the Micronesian Archipelago, perhaps we can reconnoitre it from the summit of this mountain, and then we will consider how to establish ourselves here as if we were never going to leave it.”

“Never?” cried the reporter. “Do you say never, my dear Cyrus?”

“It is better to put things in their worst light at first,” answered the engineer; “and to reserve those which are better, as a surprise.”

“Well said,” replied Pencroff. “And we hope that this island, if it is an island, will not be situated just outside of the route of ships; for that would, indeed, be unlucky.”

“We will know how to act after having first ascended the mountain,” answered Smith.

“But will you be able, Mr. Smith, to make the climb tomorrow?” asked Herbert.

“I hope so,” answered the engineer, “if Pencroff and you, my boy, show yourselves to be good and ready hunters.”

“Mr. Smith,” said the sailor, “since you are speaking of game, if when I come back I am as sure of getting it roasted as I am of bringing it—”

“Bring it, nevertheless,” interrupted Smith.

It was now agreed that the engineer and the reporter should spend the day at the Chimneys, in order to examine the shore and the plateau, while Neb, Herbert, and the sailor were to return to the forest, renew the supply of wood, and lay hands on every bird and beast that should cross their path. So, at 6 o’clock, the party left, Herbert confident. Neb happy, and Pencroff muttering to himself:—

“If, when I get back I find a fire in the house, it will have been the lightning that lit it!”

The three climbed the bank, and having reached the turn in the river, the sailor stopped and said to his companions:—

“Shall we begin as hunters or wood-choppers?”

“Hunters,” answered Herbert. “See Top, who is already at it.”

“Let us hunt, then,” replied the sailor, “and on our return here we will lay in our stock of wood.”

This said, the party made three clubs for themselves, and followed Top, who was jumping about in the high grass.

This time, the hunters, instead of following the course of the stream, struck at once into the depths of the forests. The trees were for the most part of the pine family. And in certain places, where they stood in small groups, they were of such a size as to indicate that this country was in a higher latitude than the engineer supposed. Some openings, bristling with stumps decayed by the weather, were covered with dead timber which formed an inexhaustible reserve of firewood. Then, the opening passed, the underwood became so thick as to be nearly impenetrable.

To guide oneself among these great trees without any beaten path was very difficult. So the sailer from time to time blazed the route by breaking branches in a manner easily recognizable. But perhaps they would have done better to have followed the water course, as in the first instance, as, after an hour’s march, no game had been taken. Top, running under the low boughs, only flushed birds that were unapproachable. Even the couroucous were invisible, and it seemed likely that the sailor would be obliged to return to that swampy place where he had fished for tetras with such good luck.

“Well, Pencroff,” said Neb sarcastically, “if this is all the game you promised to carry back to my master it won’t take much fire to roast it!”

“Wait a bit, Neb,” answered the sailor; “it won’t be game that will be wanting on our return.”

“Don’t you believe in Mr. Smith?”

“Yes.”

“But you don’t believe be will make a fire?”

“I will believe that when the wood is blazing in the fire-place.”

“It will blaze, then, for my master has said so!”

“Well, we’ll see!”

Meanwhile the sun had not yet risen to its highest point above the horizon. The exploration went on and was signalized by Herbert’s discovery of a tree bearing edible fruit. It was the pistachio pine, which bears an excellent nut, much liked in the temperate regions of America and Europe. These nuts were perfectly ripe, and Herbert showed them to his companions, who feasted on them.

“Well,” said Pencroff, “seaweed for bread, raw mussels for meat, and nuts for dessert, that’s the sort of dinner for men who haven’t a match in their pocket!”

“It’s not worth while complaining,” replied Herbert.

“I don’t complain, my boy. I simply repeat that the meat is a little too scant in this sort of meal.”

“Top has seen something!” cried Neb, running toward a thicket into which the dog had disappeared barking. With the dog’s barks were mingled singular gruntings. The sailor and Herbert had followed the negro. If it was game, this was not the time to discuss how to cook it, but rather how to secure it.

The hunters, on entering the brush, saw Top struggling with an animal which he held by the ear. This quadruped was a species of pig, about two feet and a half long, of a brownish black color, somewhat lighter under the belly, having harsh and somewhat scanty hair, and its toes at this time strongly grasping the soil seemed joined together by membranes.

Herbert thought that he recognized in this animal a cabiai, or water-hog, one of the largest specimens of the order of rodents. The water-hog did not fight the dog. Its great eyes, deep sank in thick layers of fat, rolled stupidly from side to side. And Neb, grasping his club firmly, was about to knock the beast down, when the latter tore loose from Top, leaving a piece of his ear in the dog’s mouth, and uttering a vigorous grunt, rushed against and overset Herbert and disappeared in the wood.

“The beggar!” cried Pencroff, as they all three darted after the hog. But just as they had come up to it again, the water-hog disappeared under the surface of a large pond, overshadowed by tall, ancient pines.

The three companions stopped, motionless. Top had plunged into the water, but the cabiai, hidden at the bottom of the pond, did not appear.

“Wait,”, said the boy, “he will have to come to the surface to breathe.”

“Won’t he drown?” asked Neb.

“No,” answered Herbert, “since he is fin-toed and almost amphibious. But watch for him.”

Top remained in the water, and Pencroff and his companions took stations upon the bank, to cut off the animal’s retreat, while the dog swam to and fro looking for him.

Herbert was not mistaken. In a few minutes the animal came again to the surface. Top was upon him at once, keeping him from diving again, and a moment later, the cabiai, dragged to the shore, was struck down by a blow from Neb’s club.

“Hurrah!” cried Pencroff with all his heart. “Nothing but a clear fire, and this gnawer shall be gnawed to the bone.”

Pencroff lifted the carcase to his shoulder, and judging by the sun that it must be near 2 o’clock, he gave the signal to return.

Top’s instinct was useful to the hunters, as, thanks to that intelligent animal, they were enabled to return upon their steps. In half an hour they had reached the bend of the river. There, as before, Pencroff quickly constructed a raft, although, lacking fire, this seemed to him a useless job, and, with the raft keeping the current, they returned towards the Chimneys. But the sailor had not gone fifty paces when he stopped and gave utterance anew to a tremendous hurrah, and extending his hand towards the angle of the cliff—

“Herbert! Neb! See!” he cried.

Smoke was escaping and curling above the rocks!

CHAPTER X.THE ENGINEER’S INVENTION—ISLAND OR CONTINENT?—DEPARTURE FOR THE MOUNTAIN—THE FOREST—VOLCANIC SOIL—THE TRAGOPANS—THE MOUFFLONS —THE FIRST PLATEAU—ENCAMPING FOR THE NIGHT—THE SUMMIT OF THE CONE

A few minutes afterwards, the three hunters were seated before a sparkling fire. Beside them sat Cyrus Smith and the reporter. Pencroff looked from one to the other without saying a word, his cabiai in his hand.

“Yes, my good fellow,” said the reporter, “a fire, a real fire, that will roast your game to a turn.”

“But who lighted it?” said the sailor.

“The sun.”

The sailor could not believe his eyes, and was too stupefied to question the engineer.

“Had you a burning-glass, sir?” asked Herbert of Cyrus Smith.

“No, my boy,” said he, “but I made one.”

And he showed his extemporized lens. It was simply the two glasses, from his own watch and the reporter’s, which he had taken out, filled with water, and stuck together at the edges with a little clay. Thus he had made a veritable burning-glass, and by concentrating the solar rays on some dry moss had set it on fire.

The sailor examined the lens; then he looked at the engineer without saying a word, but his face spoke for him. If Smith was not a magician to him, he was certainly more than a man. At last his speech returned, and he said:—

“Put that down, Mr. Spilett, put that down in your book!”

“I have it down,” said the reporter.

Then, with the help of Neb, the sailor arranged the spit, and dressed the cabiai for roasting, like a suckling pig, before the sparkling fire, by whose warmth, and by the restoration of the partitions, the Chimneys had been rendered habitable.

The engineer and his companion had made good use of their day. Smith had almost entirely recovered his strength, which he had tested by climbing the plateau above. From thence his eye, accustomed to measure heights and distances, had attentively examined the cone whose summit he proposed to reach on the morrow. The mountain, situated about six miles to the northwest, seemed to him to reach about 3,500 feet above the level of the sea, so that an observer posted at its summit, could command a horizon of fifty miles at least. He hoped, therefore, for an easy solution of the urgent question, “Island or continent?”

They had a pleasant supper, and the meat of the cabiai was proclaimed excellent; the sargassum and pistachio-nuts completed the repast. But the engineer said little; he was planning for the next day. Once or twice Pencroff talked of some project for the future, but Smith shook his head.

“To-morrow,” he said, “we will know how we are situated, and we can act accordingly.”

After supper, more armfuls of wood were thrown on the fire, and the party lay down to sleep. The morning found

Comments (0)