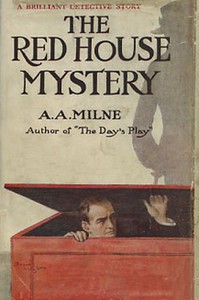

The Red House Mystery, A. A. Milne [the little red hen ebook .txt] 📗

- Author: A. A. Milne

Book online «The Red House Mystery, A. A. Milne [the little red hen ebook .txt] 📗». Author A. A. Milne

“I say, what fun! You do want me, don’t you?”

“Of course I do. Only, Bill don’t talk about things inside the house, unless I begin. There’s a good Watson.”

“I won’t. I swear I won’t.”

They had come to the pond—Mark’s lake—and they walked silently round it. When they had made the circle, Antony sat down on the grass, and relit his pipe. Bill followed his example.

“Well, Mark isn’t there,” said Antony.

“No,” said Bill. “At least, I don’t quite see why you know he isn’t.”

“It isn’t ‘knowing,’ it’s ‘guessing,’” said Antony rapidly. “It’s much easier to shoot yourself than to drown yourself, and if Mark had wanted to shoot himself in the water, with some idea of not letting the body be found, he’d have put big stones in his pockets, and the only big stones are near the water’s edge, and they would have left marks, and they haven’t, and therefore he didn’t, and—oh, bother the pond; that can wait till this afternoon. Bill, where does the secret passage begin?”

“Well, that’s what we’ve got to find out, isn’t it?”

“Yes. You see, my idea is this.”

He explained his reasons for thinking that the secret of the passage was concerned in some way with the secret of Robert’s death, and went on:

“My theory is that Mark discovered the passage about a year ago—the time when he began to get keen on croquet. The passage came out into the floor of the shed, and probably it was Cayley’s idea to put a croquet-box over the trap-door, so as to hide it more completely. You know, when once you’ve discovered a secret yourself, it always seems as if it must be so obvious to everybody else. I can imagine that Mark loved having this little secret all to himself—and to Cayley, of course, but Cayley wouldn’t count—and they must have had great fun fixing it up, and making it more difficult for other people to find out. Well then, when Miss Norris was going to dress-up, Cayley gave it away. Probably he told her that she could never get down to the bowling-green without being discovered, and then perhaps showed that he knew there was one way in which she could do it, and she wormed the secret out of him somehow.”

“But this was two or three days before Robert turned up.”

“Exactly. I am not suggesting that there was anything sinister about the passage in the first place. It was just a little private bit of romance and adventure for Mark, three days ago. He didn’t even know that Robert was coming. But somehow the passage has been used since, in connection with Robert. Perhaps Mark escaped that way; perhaps he’s hiding there now. And if so, then the only person who could give him away was Miss Norris. And she of course would only do it innocently—not knowing that the passage had anything to do with it.”

“So it was safer to have her out of the way?”

“Yes.”

“But, look here, Tony, why do you want to bother about this end of it? We can always get in at the bowling-green end.”

“I know, but if we do that we shall have to do it openly. It will mean breaking open the box, and letting Cayley know that we’ve done it. You see, Bill, if we don’t find anything out for ourselves in the next day or two, we’ve got to tell the police what we have found out, and then they can explore the passage for themselves. But I don’t want to do that yet.”

“Rather not.”

“So we’ve got to carry on secretly for a bit. It’s the only way.” He smiled and added, “And it’s much more fun.”

“Rather!” Bill chuckled to himself.

“Very well. Where does the secret passage begin?”

The Reverend Theodore Ussher

“There’s one thing, which we have got to realize at once,” said Antony, “and that is that if we don’t find it easily, we shan’t find it at all.”

“You mean that we shan’t have time?”

“Neither time nor opportunity. Which is rather a consoling thought to a lazy person like me.”

“But it makes it much harder, if we can’t really look properly.”

“Harder to find, yes, but so much easier to look. For instance, the passage might begin in Cayley’s bedroom. Well, now we know that it doesn’t.”

“We don’t know anything of the sort,” protested Bill.

“We know for the purposes of our search. Obviously we can’t go tailing into Cayley’s bedroom and tapping his wardrobes; and obviously, therefore, if we are going to look for it at all, we must assume that it doesn’t begin there.”

“Oh, I see.” Bill chewed a piece of grass thoughtfully. “Anyhow, it wouldn’t begin on an upstairs floor, would it?”

“Probably not. Well, we’re getting on.”

“You can wash out the kitchen and all that part of the house,” said Bill, after more thought. “We can’t go there.”

“Right. And the cellars, if there are any.”

“Well, that doesn’t leave us much.”

“No. Of course it’s only a hundred-to-one chance that we find it, but what we want to consider is which is the most likely place of the few places in which we can look safely.”

“All it amounts to,” said Bill, “is the living-rooms downstairs—dining-room, library, hall, billiard-room and the office rooms.”

“Yes, that’s all.”

“Well, the office is the most likely, isn’t it?”

“Yes. Except for one thing.”

“What’s that?”

“Well, it’s on the wrong side of the house. One would expect the passage to start from the nearest place to which it is going. Why make it longer by going under the house first?”

“Yes, that’s true. Well, then, you think the dining-room or the library?”

“Yes. And the library for choice. I mean for our choice. There are always servants going into dining-rooms. We shouldn’t have much of a chance of exploring properly in there. Besides, there’s another thing to remember. Mark has kept this a secret for a year. Could he have kept it a secret in the dining-room? Could Miss Norris have got into the dining-room and used the secret door just after dinner without being seen? It would have been much too risky.”

Bill got up eagerly.

“Come along,” he said, “let’s try the library. If Cayley comes in, we can always pretend we’re choosing a book.”

Antony got up slowly, took his arm and walked back to the house with him.

The library was worth going into, passages or no passages. Antony could never resist another person’s bookshelves. As soon as he went into the room, he found himself wandering round it to see what books the owner read, or (more likely) did not read, but kept for the air which they lent to the house. Mark had prided himself on his library. It was a mixed collection of books. Books which he had inherited both from his father and from his patron; books which he had bought because he was interested in them or, if not in them, in the authors to whom he wished to lend his patronage; books which he had ordered in beautifully bound editions, partly because they looked well on his shelves, lending a noble colour to his rooms, partly because no man of culture should ever be without them; old editions, new editions, expensive books, cheap books—a library in which everybody, whatever his taste, could be sure of finding something to suit him.

“And which is your particular fancy, Bill?” said Antony, looking from one shelf to another. “Or are you always playing billiards?”

“I have a look at ‘Badminton’ sometimes,” said Bill. “It’s over in that corner there.” He waved a hand.

“Over here?” said Antony, going to it.

“Yes.” He corrected himself suddenly. “Oh, no, it’s not. It’s over there on the right now. Mark had a grand re-arrangement of his library about a year ago. It took him more than a week, he told us. He’s got such a frightful lot, hasn’t he?”

“Now that’s very interesting,” said Antony, and he sat down and filled his pipe again.

There was indeed a “frightful lot” of books. The four walls of the library were plastered with them from floor to ceiling, save only where the door and the two windows insisted on living their own life, even though an illiterate one. To Bill it seemed the most hopeless room of any in which to look for a secret opening.

“We shall have to take every blessed book down,” he said, “before we can be certain that we haven’t missed it.”

“Anyway,” said Antony, “if we take them down one at a time, nobody can suspect us of sinister designs. After all, what does one go into a library for, except to take books down?”

“But there’s such a frightful lot.”

Antony’s pipe was now going satisfactorily, and he got up and walked leisurely to the end of the wall opposite the door.

“Well, let’s have a look,” he said, “and see if they are so very frightful. Hallo, here’s your ‘Badminton.’ You often read that, you say?”

“If I read anything.”

“Yes.” He looked down and up the shelf. “Sport and Travel chiefly. I like books of travel, don’t you?”

“They’re pretty dull as a rule.”

“Well, anyhow, some people like them very much,” said Antony, reproachfully. He moved on to the next row of shelves. “The Drama. The Restoration dramatists. You can have most of them. Still, as you well remark, many people seem to love them. Shaw, Wilde, Robertson—I like reading plays, Bill. There are not many people who do, but those who do are usually very keen. Let us pass on.”

“I say, we haven’t too much time,” said Bill restlessly.

“We haven’t. That’s why we aren’t wasting any. Poetry. Who reads poetry nowadays? Bill, when did you last read ‘Paradise Lost’?”

“Never.”

“I thought not. And when did Miss Calladine last read ‘The Excursion’ aloud to you?”

“As a matter of fact, Betty—Miss Calladine—happens to be jolly keen on—what’s the beggar’s name?”

“Never mind his name. You have said quite enough. We pass on.”

He moved on to the next shelf.

“Biography. Oh, lots of it. I love biographies. Are you a member of the Johnson Club? I bet Mark is. ‘Memories of Many Courts’—I’m sure Mrs. Calladine reads that. Anyway, biographies are just as interesting as most novels, so why linger? We pass on.” He went to the next shelf, and then gave a sudden whistle. “Hallo, hallo!”

“What’s the matter?” said Bill rather peevishly.

“Stand back there. Keep the crowd back, Bill. We are getting amongst it. Sermons, as I live. Sermons. Was Mark’s father a clergyman, or does Mark take to them naturally?”

“His father was a parson, I believe. Oh, yes, I know he was.”

“Ah, then these are Father’s books. ‘Half-Hours with the Infinite’—I must order that from the library when I get back. ‘The Lost Sheep,’ ‘Jones on the Trinity,’ ‘The Epistles of St. Paul Explained.’ Oh, Bill, we’re amongst it. ‘The Narrow Way, being Sermons by the Rev. Theodore Ussher’—hal-lo!”

“What is the matter?”

“William, I am inspired. Stand by.” He took down the Reverend Theodore Ussher’s classic work, looked at it with a happy smile for a moment, and then gave it to Bill.

“Here, hold Ussher for a bit.”

Bill took the book obediently.

“No, give it me back. Just go out into the hall, and see if you can hear Cayley anywhere. Say ‘Hallo’ loudly, if you do.”

Bill went out quickly, listened, and came back.

“It’s all right.”

“Good.” He took the book out of its shelf again. “Now then, you can hold Ussher. Hold him in the left hand—so. With the right or dexter hand, grasp this shelf firmly—so. Now, when I say ‘Pull,’ pull gradually. Got that?”

Bill nodded, his face alight with excitement.

“Good.” Antony put his hand into the space left by the stout Ussher, and fingered the back of the shelf. “Pull,” he said.

Bill pulled.

“Now just go on pulling like that. I shall get it directly. Not hard, you know, but just keeping up the strain.”

His fingers went at it again busily.

And then suddenly the whole row of shelves, from top to bottom, swung gently open towards them.

“Good Lord!” said Bill, letting go of the shelf in his amazement.

Antony pushed the shelves back, extracted Ussher from Bill’s fingers, replaced him, and then, taking Bill by the arm, led him to the sofa and deposited him in it. Standing in front of him, he bowed gravely.

“Child’s play, Watson,” he said; “child’s play.”

“How on earth—”

Antony laughed happily and sat down on the sofa beside him.

“You don’t really want it explained,” he said, smacking him on the knee; “you’re just being Watsonish. It’s very nice of you, of course, and I appreciate it.”

“No, but really, Tony.”

“Oh, my dear Bill!” He smoked silently for a little, and then went on, “It’s what I was saying just now—a secret is a secret until you have discovered

Comments (0)