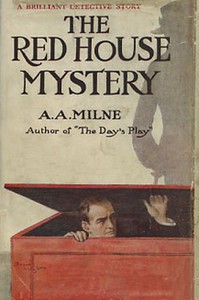

The Red House Mystery, A. A. Milne [the little red hen ebook .txt] 📗

- Author: A. A. Milne

Book online «The Red House Mystery, A. A. Milne [the little red hen ebook .txt] 📗». Author A. A. Milne

As he went into the room, followed by Bill, he felt it almost as a shock that there was now no body of Robert lying there between the two doors. But there was a dark stain which showed where the dead man’s head had been, and Antony knelt down over it, as he had knelt twenty-four hours before.

“I want to go through it again,” he said. “You must be Cayley. Cayley said he would get some water. I remember thinking that water wasn’t much good to a dead man, and that probably he was only too glad to do anything rather than nothing. He came back with a wet sponge and a handkerchief. I suppose he got the handkerchief from the chest of drawers. Wait a bit.”

He got up and went into the adjoining room; looked round it, pulled open a drawer or two, and, after shutting all the doors, came back to the office.

“The sponge is there, and there are handkerchiefs in the top right-hand drawer. Now then, Bill, just pretend you’re Cayley. You’ve just said something about water, and you get up.”

Feeling that it was all a little uncanny, Bill, who had been kneeling beside his friend, got up and walked out. Antony, as he had done on the previous day, looked up after him as he went. Bill turned into the room on the right, opened the drawer and got the handkerchief, damped the sponge and came back.

“Well?” he said wonderingly.

Antony shook his head.

“It’s all different,” he said. “For one thing, you made a devil of a noise and Cayley didn’t.”

“Perhaps you weren’t listening when Cayley went in?”

“I wasn’t. But I should have heard him if I could have heard him, and I should have remembered afterwards.”

“Perhaps Cayley shut the door after him.”

“Wait!”

He pressed his hand over his eyes and thought. It wasn’t anything which he had heard, but something which he had seen. He tried desperately hard to see it again.... He saw Cayley getting up, opening the door from the office, leaving it open and walking into the passage, turning to the door on the right, opening it, going in, and then—What did his eyes see after that? If they would only tell him again!

Suddenly he jumped up, his face alight. “Bill, I’ve got it!” he cried.

“What?”

“The shadow on the wall! I was looking at the shadow on the wall. Oh, ass, and ten times ass!”

Bill looked uncomprehendingly at him. Antony took his arm and pointed to the wall of the passage.

“Look at the sunlight on it,” he said. “That’s because you’ve left the door of that room open. The sun comes straight in through the windows. Now, I’m going to shut the door. Look! D’you see how the shadow moves across? That’s what I saw—the shadow moving across as the door shut behind him. Bill, go in and shut the door behind you—quite naturally. Quick!”

Bill went out and Antony knelt, watching eagerly.

“I thought so!” he cried. “I knew it couldn’t have been that.”

“What happened?” said Bill, coming back.

“Just what you would expect. The sunlight came, and the shadow moved back again—all in one movement.”

“And what happened yesterday?”

“The sunlight stayed there; and then the shadow came very slowly back, and there was no noise of the door being shut.”

Bill looked at him with startled eyes.

“By Jove! You mean that Cayley closed the door afterwards as an afterthought—and very quietly—so that you couldn’t hear?”

Antony nodded.

“Yes. That explains why I was surprised afterwards when I went into the room to find the door open behind me. You know how those doors with springs on them close?”

“The sort which old gentlemen have to keep out draughts?”

“Yes. Just at first they hardly move at all, and then very, very slowly they swing to— well, that was the way the shadow moved, and subconsciously I must have associated it with the movement of that sort of door. By Jove!” He got up, and dusted his knees. “Now, Bill, just to make sure, go in and close the door like that. As an afterthought, you know; and very quietly, so that I don’t hear the click of it.”

Bill did as he was told, and then put his head out eagerly to hear what had happened.

“That was it,” said Antony, with absolute conviction. “That was just what I saw yesterday.” He came out of the office, and joined Bill in the little room.

“And now,” he said, “let’s try and find out what it was that Mr. Cayley was doing in here, and why he had to be so very careful that his friend Mr. Gillingham didn’t overhear him.”

The Open Window

Anthony’s first thought was that Cayley had hidden something; something, perhaps, which he had found by the body, and—but that was absurd. In the time at his disposal, he could have done no more than put it away in a drawer, where it would be much more open to discovery by Antony than if he had kept it in his pocket. In any case he would have removed it by this time, and hidden it in some more secret place. Besides, why in this case bother about shutting the door?

Bill pulled open a drawer in the chest, and looked inside.

“Is it any good going through these, do you think?” he asked.

Antony looked over his shoulder.

“Why did he keep clothes here at all?” he asked. “Did he ever change down here?”

“My dear Tony, he had more clothes than anybody in the world. He just kept them here in case they might be useful, I expect. When you and I go from London to the country we carry our clothes about with us. Mark never did. In his flat in London he had everything all over again which he has here. It was a hobby with him, collecting clothes. If he’d had half a dozen houses, they would all have been full of a complete gentleman’s town and country outfit.”

“I see.”

“Of course, it might be useful sometimes, when he was busy in the next room, not to have to go upstairs for a handkerchief or a more comfortable coat.”

“I see. Yes.” He was walking round the room as he answered, and he lifted the top of the linen basket which stood near the wash basin and glanced in. “He seems to have come in here for a collar lately.”

Bill peered in. There was one collar at the bottom of the basket.

“Yes. I daresay he would,” he agreed. “If he suddenly found that the one he was wearing was uncomfortable or a little bit dirty, or something. He was very finicking.”

Antony leant over and picked it out.

“It must have been uncomfortable this time,” he said, after examining it carefully. “It couldn’t very well be cleaner.” He dropped it back again. “Anyway, he did come in here sometimes?”

“Oh, yes, rather.”

“Yes, but what did Cayley come in for so secretly?”

“What did he want to shut the door for?” said Bill. “That’s what I don’t understand. You couldn’t have seen him, anyhow.”

“No. So it follows that I might have heard him. He was going to do something which he didn’t want me to hear.”

“By Jove, that’s it!” said Bill eagerly.

“Yes; but what?”

Bill frowned hopefully to himself, but no inspiration came.

“Well, let’s have some air, anyway,” he said at last, exhausted by the effort, and he went to the window, opened it, and looked out. Then, struck by an idea, he turned back to Antony and said, “Do you think I had better go up to the pond to make sure that they’re still at it? Because—”

He broke off suddenly at the sight of Antony’s face.

“Oh, idiot, idiot!” Antony cried. “Oh, most super-excellent of Watsons! Oh, you lamb, you blessing! Oh, Gillingham, you incomparable ass!”

“What on earth—”

“The window, the window!” cried Antony, pointing to it.

Bill turned back to the window, expecting it to say something. As it said nothing, he looked at Antony again.

“He was opening the window!” cried Antony.

“Who?”

“Cayley, of course.” Very gravely and slowly he expounded. “He came in here in order to open the window. He shut the door so that I shouldn’t hear him open the window. He opened the window. I came in here and found the window open. I said, ‘This window is open. My amazing powers of analysis tell me that the murderer must have escaped by this window.’ ‘Oh,’ said Cayley, raising his eyebrows. ‘Well,’ said he, ‘I suppose you must be right.’ Said I proudly, ‘I am. For the window is open,’ I said. Oh, you incomparable ass!”

He understood now. It explained so much that had been puzzling him.

He tried to put himself in Cayley’s place—Cayley, when Antony had first discovered him, hammering at the door and crying, “Let me in!” Whatever had happened inside the office, whoever had killed Robert, Cayley knew all about it, and knew that Mark was not inside, and had not escaped by the window. But it was necessary to Cayley’s plans—to Mark’s plans if they were acting in concert—that he should be thought so to have escaped. At some time, then, while he was hammering (the key in his pocket) at the locked door, he must suddenly have remembered—with what a shock!—that a mistake had been made. A window had not been left open!

Probably it would just have been a horrible doubt at first. Was the office window open? Surely it was open! Was it?.... Would he have time now to unlock the door, slip in, open the French windows and slip out again? No. At any moment the servants might come. It was too risky. Fatal, if he were discovered. But servants were stupid. He could get the windows safely open while they were crowding round the body. They wouldn’t notice. He could do it somehow.

And then Antony’s sudden appearance! Here was a complication. And Antony suggesting that they should try the window! Why, the window was just what he wanted to avoid. No wonder he had seemed dazed at first.

Ah, and here at last was the explanation why they had gone the longest way round and yet run. It was Cayley’s only chance of getting a start on Antony, of getting to the windows first, of working them open somehow before Antony caught him up. Even if that were impossible, he must get there first, just to make sure. Perhaps they were open. He must get away from Antony and see. And if they were shut, hopelessly shut, then he must have a moment to himself, a moment in which to think of some other plan, and avoid the ruin which seemed so suddenly to be threatening.

So he had run. But Antony had kept up with him. They had broken in the window together, and gone into the office. But Cayley was not done yet. There was the dressing-room window! But quietly, quietly. Antony mustn’t hear.

And Antony didn’t hear. Indeed, he had played up to Cayley splendidly. Not only had he called attention to the open window, but he had carefully explained to Cayley why Mark had chosen this particular window in preference to the office window. And Cayley had agreed that probably that was the reason. How he must have chuckled to himself! But he was still a little afraid. Afraid that Antony would examine the shrubbery. Why? Obviously because there was no trace of anyone having broken through the shrubbery. No doubt Cayley had provided the necessary traces since, and had helped the Inspector to find them. Had he even gone as far as footmarks—in Mark’s shoes? But the ground was very hard. Perhaps footmarks were not necessary. Antony smiled as he thought of the big Cayley trying to squeeze into the dapper little Mark’s shoes. Cayley must have been glad that footmarks were not necessary.

No, the open window was enough; the open window and a broken twig or two. But quietly, quietly. Antony mustn’t hear. And Antony had not heard.... But he had seen a shadow on the wall.

They were outside on the lawn again now, Bill and Antony, and Bill was listening open-mouthed to his friend’s theory of yesterday’s happenings. It fitted in, it explained things, but it did not get them any further. It only gave them another mystery to solve.

“What’s that?” said Antony.

“Mark. Where’s Mark? If he never went into the office at all, then where is he now?”

“I don’t say that he never went into the office. In fact, he must have gone. Elsie heard him.” He stopped and repeated slowly, “She heard

Comments (0)