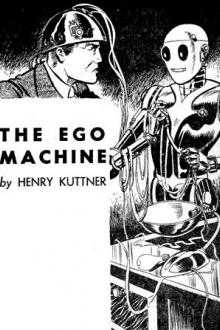

The Ego Machine, Henry Kuttner [online e book reader txt] 📗

- Author: Henry Kuttner

Book online «The Ego Machine, Henry Kuttner [online e book reader txt] 📗». Author Henry Kuttner

"Oh, have a drink," Martin said. "I feel hospitable. Go ahead, indulge me, will you? My pleasures are few. And I've got to go and be terrorized in a minute, anyhow. If you can't get that mask off I'll send for a straw. You can step out of character long enough for one jolt, can't you?"

"I'd like to try it," the robot said pensively. "Ever since I noticed the effect fermented mammoth's milk had on the boys, it's been on my mind, rather. Quite easy for a human, of course. Technically it's simple enough, I see now. The irritation just increases the frequency of the brain's kappa waves, as with boosted voltage, but since electrical voltage never existed in pre-robot times—"

"It did," Martin said, taking another drink. "I mean, it does. What do you call that, a mammoth?" He indicated the desk lamp.

The robot's jaw dropped.

"That?" he asked in blank amazement. "Why—why then all those telephone poles and dynamos and lighting-equipment I noticed in this era are powered by electricity!"

"What did you think they were powered by?" Martin asked coldly.

"Slaves," the robot said, examining the lamp. He switched it on, blinked, and then unscrewed the bulb. "Voltage, you say?"

"Don't be a fool," Martin said. "You're overplaying your part. I've got to get going in a minute. Do you want a jolt or don't you?"

"Well," the robot said, "I don't want to seem unsociable. This ought to work." So saying, he stuck his finger in the lamp-socket. There was a brief, crackling flash. The robot withdrew his finger.

"F(t)—" he said, and swayed slightly. Then his fingers came up and sketched a smile that seemed, somehow, to express delighted surprise.

"Fff(t)!" he said, and went on rather thickly, "F(t) integral between plus and minus infinity ... a-sub-n to e...."

Martin's eyes opened wide with shocked horror. Whether a doctor or a psychiatrist should be called in was debatable, but it was perfectly evident that this was a case for the medical profession, and the sooner the better. Perhaps the police, too. The bit-player in the robot suit was clearly as mad as a hatter. Martin poised indecisively, waiting for his lunatic guest either to drop dead or spring at his throat.

The robot appeared to be smacking his lips, with faint clicking sounds.

"Why, that's wonderful," he said. "AC, too."

"Y-you're not dead?" Martin inquired shakily.

"I'm not even alive," the robot murmured. "The way you'd understand it, that is. Ah—thanks for the jolt."

Martin stared at the robot with the wildest dawning of surmise.

"Why—" he gasped. "Why—you're a robot!"

"Certainly I'm a robot," his guest said. "What slow minds you pre-robots had. Mine's working like lightning now." He stole a drunkard's glance at the desk-lamp. "F(t)—I mean, if you counted the kappa waves of my radio-atomic brain now, you'd be amazed how the frequency's increased." He paused thoughtfully. "F(t)," he added.

Moving quite slowly, like a man under water, Martin lifted his glass and drank whiskey. Then, cautiously, he looked up at the robot again.

"F(t)—" he said, paused, shuddered, and drank again. That did it. "I'm drunk," he said with an air of shaken relief. "That must be it. I was almost beginning to believe—"

"Oh, nobody believes I'm a robot at first," the robot said. "You'll notice I showed up in a movie lot, where I wouldn't arouse suspicion. I'll appear to Ivan Vasilovich in an alchemist's lab, and he'll jump to the conclusive I'm an automaton. Which, of course, I am. Then there's a Uighur on my list—I'll appear to him in a shaman's hut and he'll assume I'm a devil. A matter of ecologicologic."

"Then you're a devil?" Martin inquired, seizing on the only plausible solution.

"No, no, no. I'm a robot. Don't you understand anything?"

"I don't even know who I am, now," Martin said. "For all I know, I'm a faun and you're a human child. I don't think this Scotch is doing me as much good as I'd—"

"Your name is Nicholas Martin," the robot said patiently. "And mine is ENIAC."

"Eniac?"

"ENIAC," the robot corrected, capitalizing. "ENIAC Gamma the Ninety-Third."

So saying, he unslung a sack from his metallic shoulder and began to rummage out length upon length of what looked like red silk ribbon with a curious metallic lustre. After approximately a quarter-mile of it had appeared, a crystal football helmet emerged attached to its end. A gleaming red-green stone was set on each side of the helmet.

"Just over the temporal lobes, you see," the robot explained, indicating the jewels. "Now you just set it on your head, like this—"

"Oh no I don't," Martin said, withdrawing his head with the utmost rapidity. "Neither do you, my friend. What's the idea? I don't like the looks of that gimmick. I particularly don't like those two red garnets on the sides. They look like eyes."

"Those are artificial eclogite," the robot assured him. "They simply have a high dielectric constant. It's merely a matter of altering the normal thresholds of the neuron memory-circuits. All thinking is based on memory, you know. The strength of your associations—the emotional indices of your memories—channel your actions and decisions, and the ecologizer simply changes the voltage of your brain so the thresholds are altered."

"Is that all it does?" Martin asked suspiciously.

"Well, now," the robot said with a slight air of evasion. "I didn't intend to mention it, but since you ask—it also imposes the master-matrix of your character type. But since that's the prototype of your character in the first place, it will simply enable you to make the most of your potential ability, hereditary and acquired. It will make you react to your environment in the way that best assures your survival."

"Not me, it won't," Martin said firmly. "Because you aren't going to put that thing on my head."

The robot sketched a puzzled frown. "Oh," he said after a pause. "I haven't explained yet, have I? It's very simple. Would you be willing to take part in a valuable socio-cultural experiment for the benefit of all mankind?"

"No," Martin said.

"But you don't know what it is yet," the robot said plaintively. "You'll be the only one to refuse, after I've explained everything thoroughly. By the way, can you understand me all right?"

Martin laughed hollowly. "Natch," he said.

"Good," the robot said, relieved. "That may be one trouble with my memory. I had to record so many languages before I could temporalize. Sanskrit's very simple, but medieval Russian's confusing, and as for Uighur—however! The purpose of this experiment is to promote the most successful pro-survival relationship between man and his environment. Instant adaptation is what we're aiming at, and we hope to get it by minimizing the differential between individual and environment. In other words, the right reaction at the right time. Understand?"

"Of course not," Martin said. "What nonsense you talk."

"There are," the robot said rather wearily, "only a limited number of character matrices possible, depending first on the arrangement of the genes within the chromosomes, and later upon environmental additions. Since environments tend to repeat—like societies, you know—an organizational pattern isn't hard to lay out, along the Kaldekooz time-scale. You follow me so far?"

"By the Kaldekooz time-scale, yes," Martin said.

"I was always lucid," the robot remarked a little vainly, nourishing a swirl of red ribbon.

"Keep that thing away from me," Martin complained. "Drunk I may be, but I have no intention of sticking my neck out that far."

"Of course you'll do it," the robot said firmly. "Nobody's ever refused yet. And don't bicker with me or you'll get me confused and I'll have to take another jolt of voltage. Then there's no telling how confused I'll be. My memory gives me enough trouble when I temporalize. Time-travel always raises the synaptic delay threshold, but the trouble is it's so variable. That's why I got you mixed up with Ivan at first. But I don't visit him till after I've seen you—I'm running the test chronologically, and nineteen-fifty-two comes before fifteen-seventy, of course."

"It doesn't," Martin said, tilting the glass to his lips. "Not even in Hollywood does nineteen-fifty-two come before fifteen-seventy."

"I'm using the Kaldekooz time-scale," the robot explained. "But really only for convenience. Now do you want the ideal ecological differential or don't you? Because—" Here he flourished the red ribbon again, peered into the helmet, looked narrowly at Martin, and shook his head.

"I'm sorry," the robot said. "I'm afraid this won't work. Your head's too small. Not enough brain-room, I suppose. This helmet's for an eight and a half head, and yours is much too—"

"My head is eight and a half," Martin protested with dignity.

"Can't be," the robot said cunningly. "If it were, the helmet would fit, and it doesn't. Too big."

"It does fit," Martin said.

"That's the trouble with arguing with pre-robot species," ENIAC said, as to himself. "Low, brutish, unreasoning. No wonder, when their heads are so small. Now Mr. Martin—" He spoke as though to a small, stupid, stubborn child. "Try to understand. This helmet's size eight and a half. Your head is unfortunately so very small that the helmet wouldn't fit—"

"Blast it!" cried the infuriated Martin, caution quite lost between Scotch and annoyance. "It does fit! Look here!" Recklessly he snatched the helmet and clapped it firmly on his head. "It fits perfectly!"

"I erred," the robot acknowledged, with such a gleam in his eye that Martin, suddenly conscious of his rashness, jerked the helmet from his head and dropped it on the desk. ENIAC quietly picked it up and put it back into his sack, stuffing the red ribbon in after it with rapid motions. Martin watched, baffled, until ENIAC had finished, gathered together the mouth of the sack, swung it on his shoulder again, and turned toward the door.

"Good-bye," the robot said. "And thank you."

"For what?" Martin demanded.

"For your cooperation," the robot said.

"I won't cooperate," Martin told him flatly. "It's no use. Whatever fool treatment it is you're selling, I'm not going to—"

"Oh, you've already had the ecology treatment," ENIAC replied blandly. "I'll be back tonight to renew the charge. It lasts only twelve hours."

"What!"

ENIAC moved his forefingers outward from the corners of his mouth, sketching a polite smile. Then he stepped through the door and closed it behind him.

Martin made a faint squealing sound, like a stuck but gagged pig.

Something was happening inside his head.

IINicholas Martin felt like a man suddenly thrust under an ice-cold shower. No, not cold—steaming hot. Perfumed, too. The wind that blew in from the open window bore with it a frightful stench of gasoline, sagebrush, paint, and—from the distant commissary—ham sandwiches.

"Drunk," he thought frantically. "I'm drunk—or crazy!" He sprang up and spun around wildly; then catching sight of a crack in the hardwood floor he tried to walk along it. "Because if I can walk a straight line," he thought, "I'm not drunk. I'm only crazy...." It was not a very comforting thought.

He could walk it, all right. He could walk a far straighter line than the crack, which he saw now was microscopically jagged. He had, in fact, never felt such a sense of location and equilibrium in his life. His experiment carried him across the room to a wall-mirror, and as he straightened to look into it, suddenly all confusion settled and ceased. The violent sensory perceptions leveled off and returned to normal.

Everything was quiet. Everything was all right.

Martin met his own eyes in the mirror.

Everything was not all right.

He was stone cold sober. The Scotch he had drunk might as well have been spring-water. He leaned closer to the mirror, trying to stare through his own eyes into the depths of his brain. For something extremely odd was happening in there. All over his brain, tiny shutters were beginning to move, some sliding up till only a narrow crack remained, through which the beady little eyes of neurons could be seen peeping, some sliding down with faint crashes, revealing the agile, spidery forms of still other neurons scuttling for cover.

Altered thresholds, changing the yes-and-no reaction time of the memory-circuits, with their key emotional indices and associations ... huh?

The robot!

Martin's head swung toward the closed office door. But he made no further move. The look of blank panic on his face very slowly, quite unconsciously, began to change. The robot ... could wait.

Automatically Martin raised his hand, as though to adjust an invisible monocle. Behind him, the telephone began to ring. Martin glanced at it.

His lips curved into an insolent smile.

Flicking dust from his lapel with a suave gesture, Martin picked up the telephone. He said nothing. There was a long silence. Then a hoarse voice shouted, "Hello, hello, hello! Are you there? You, Martin!"

Martin said absolutely nothing at all.

"You keep me waiting," the voice bellowed. "Me, St. Cyr! Now jump! The rushes are ... Martin, do you hear

Comments (0)