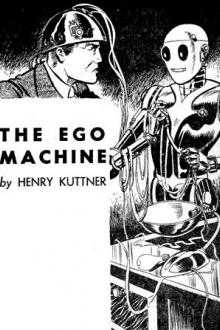

The Ego Machine, Henry Kuttner [online e book reader txt] 📗

- Author: Henry Kuttner

Book online «The Ego Machine, Henry Kuttner [online e book reader txt] 📗». Author Henry Kuttner

"Tolliver went away, I think. I've got it mixed up with the picture. He went home to meet Nick Martin, didn't he?"

"See?" Martin interrupted, relieved. "No use expecting DeeDee to—"

"But Martin is here!" St. Cyr shouted. "Think, think!"

"Was the contract release in the rushes?" DeeDee asked vaguely.

"A contract release?" St. Cyr roared. "What is this? Never will I permit it, never, never, never! DeeDee, answer me—where has Watt gone?"

"He went somewhere with that agent," DeeDee said. "Or was that in the rushes too?"

"But where, where, where?"

"They went to Atlantis," DeeDee announced with an air of faint triumph.

"No!" shouted St. Cyr. "That was the picture! The mermaid came from Atlantis, not Watt!"

"Tolliver didn't say he was coming from Atlantis," DeeDee murmured, unruffled. "He said he was going to Atlantis. Then he was going to meet Nick Martin at his house tonight and give him his contract release."

"When?" St. Cyr demanded furiously. "Think, DeeDee? What time did—"

"DeeDee," Martin said, stepping forward with suave confidence, "you can't remember a thing, can you?" But DeeDee was too subnormal to react even to a Disraeli-matrix. She merely smiled placidly at him.

"Out of my way, you writer!" roared St. Cyr, advancing upon Martin. "You will get no contract release! You do not waste St. Cyr's time and get away with it! This I will not endure. I fix you as I fixed Ed Cassidy!"

Martin drew himself up and froze St. Cyr with an insolent smile. His hand toyed with an imaginary monocle. Golden periods were hanging at the end of his tongue. There only remained to hypnotize St. Cyr as he had hypnotized Watt. He drew a deep breath to unlease the floods of his eloquence—

And St. Cyr, also too subhuman to be impressed by urbanity, hit Martin a clout on the jaw.

It could never have happened in the British Parliament.

IIIWhen the robot walked into Martin's office that evening, he, or it, went directly to the desk, unscrewed the bulb from the lamp, pressed the switch, and stuck his finger into the socket. There was a crackling flash. ENIAC withdrew his finger and shook his metallic head violently.

"I needed that," he sighed. "I've been on the go all day, by the Kaldekooz time-scale. Paleolithic, Neolithic, Technological—I don't even know what time it is. Well, how's your ecological adjustment getting on?"

Martin rubbed his chin thoughtfully.

"Badly," he said. "Tell me, did Disraeli, as Prime Minister, ever have any dealings with a country called Mixo-Lydia?"

"I have no idea," said the robot. "Why do you ask?"

"Because my environment hauled back and took a poke at my jaw," Martin said shortly.

"Then you provoked it," ENIAC countered. "A crisis—a situation of stress—always brings a man's dominant trait to the fore, and Disraeli was dominantly courageous. Under stress, his courage became insolence. But he was intelligent enough to arrange his environment so insolence would be countered on the semantic level. Mixo-Lydia, eh? I place it vaguely, some billions of years ago, when it was inhabited by giant white apes. Or—oh, now I remember. It's an encysted medieval survival, isn't it?"

Martin nodded.

"So is this movie studio," the robot said. "Your trouble is that you've run up against somebody who's got a better optimum ecological adjustment than you have. That's it. This studio environment is just emerging from medievalism, so it can easily slip back into that plenum when an optimum medievalist exerts pressure. Such types caused the Dark Ages. Well, you'd better change your environment to a neo-technological one, where the Disraeli matrix can be successfully pro-survival. In your era, only a few archaic social-encystments like this studio are feudalistic, so go somewhere else. It takes a feudalist to match a feudalist."

"But I can't go somewhere else," Martin complained. "Not without my contract release. I was supposed to pick it up tonight, but St. Cyr found out what was happening, and he'll throw a monkey-wrench in the works if he has to knock me out again to do it. I'm due at Watt's place now, but St. Cyr's already there—"

"Spare me the trivia," the robot said, raising his hand. "As for this St. Cyr, if he's a medieval character-type, obviously he'll knuckle under only to a stronger man of his own kind."

"How would Disraeli have handled this?" Martin demanded.

"Disraeli would never have got into such a situation in the first place," the robot said unhelpfully. "The ecologizer can give you the ideal ecological differential, but only for your own type, because otherwise it wouldn't be your optimum. Disraeli would have been a failure in Russia in Ivan's time."

"Would you mind clarifying that?" Martin asked thoughtfully.

"Certainly," the robot said with great rapidity. "It all depends on the threshold-response-time of the memory-circuits in the brain, if you assume the identity of the basic chromosome-pattern. The strength of neuronic activation varies in inverse proportion to the quantative memory factor. Only actual experience could give you Disraeli's memories, but your reactivity-thresholds have been altered until perception and emotional-indices approximate the Disraeli ratio."

"Oh," Martin said. "But how would you, say, assert yourself against a medieval steam-shovel?"

"By plugging my demountable brain into a larger steam-shovel," ENIAC told him.

Martin seemed pensive. His hand rose, adjusting an invisible monocle, while a look of perceptive imagination suddenly crossed his face.

"You mentioned Russia in Ivan's time," he said. "Which Ivan would that be? Not, by any chance—?"

"Ivan the Fourth. Very well adjusted to his environment he was, too. However, enough of this chit-chat. Obviously you'll be one of the failures in our experiment, but our aim is to strike an average, so if you'll put the ecologizer on your—"

"That was Ivan the Terrible, wasn't it?" Martin interrupted. "Look here, could you impress the character-matrix of Ivan the Terrible on my brain?"

"That wouldn't help you a bit," the robot said. "Besides, it's not the purpose of the experiment. Now—"

"One moment. Disraeli can't cope with a medievalist like St. Cyr on his own level, but if I had Ivan the Terrible's reactive thresholds, I'll bet I could throw a bluff that might do the trick. Even though St. Cyr's bigger than I am, he's got a veneer of civilization ... now wait. He trades on that. He's always dealt with people who are too civilized to use his own methods. The trick would be to call his bluff. And Ivan's the man who could do it."

"But you don't understand."

"Didn't everybody in Russia tremble with fear at Ivan's name?"

"Yes, in—"

"Very well, then," Martin said triumphantly. "You're going to impress the character-matrix, of Ivan the Terrible on my mind, and then I'm going to put the bite on St. Cyr, the way Ivan would have done it. Disraeli's simply too civilized. Size is a factor, but character's more important. I don't look like Disraeli, but people have been reacting to me as though I were George Arliss down to the spit-curl. A good big man can always lick a good little man. But St. Cyr's never been up against a really uncivilized little man—one who'd gladly rip out an enemy's heart with his bare hands." Martin nodded briskly. "St. Cyr will back down—I've found that out. But it would take somebody like Ivan to make him stay all the way down."

"If you think I'm going to impress Ivan's matrix on you, you're wrong," the robot said.

"You couldn't be talked into it?"

"I," said ENIAC, "am a robot, semantically adjusted. Of course you couldn't talk me into it."

Perhaps not, Martin reflected, but Disraeli—hm-m. "Man is a machine." Why, Disraeli was the one person in the world ideally fitted for robot-coercion. To him, men were machines—and what was ENIAC?

"Let's talk this over—" Martin began, absently pushing the desk-lamp toward the robot. And then the golden tongue that had swayed empires was loosed....

"You're not going to like this," the robot said dazedly, sometime later. "Ivan won't do at ... oh, you've got me all confused. You'll have to eyeprint a—" He began to pull out of his sack the helmet and the quarter-mile of red ribbon.

"To tie up my bonny grey brain," Martin said, drunk with his own rhetoric. "Put it on my head. That's right. Ivan the Terrible, remember. I'll fix St. Cyr's Mixo-Lydian wagon."

"Differential depends on environment as much as on heredity," the robot muttered, clapping the helmet on Martin's head. "Though naturally Ivan wouldn't have had the Tsardom environment without his particular heredity, involving Helena Glinska—there!" He removed the helmet.

"But nothing's happening," Martin said. "I don't feel any different."

"It'll take a few moments. This isn't your basic character-pattern, remember, as Disraeli's was. Enjoy yourself while you can. You'll get the Ivan-effect soon enough." He shouldered the sack and headed uncertainly for the door.

"Wait," Martin said uneasily. "Are you sure—"

"Be quiet. I forgot something—some formality—now I'm all confused. Well, I'll think of it later, or earlier, as the case may be. I'll see you in twelve hours—I hope."

The robot departed. Martin shook his head tentatively from side to side. Then he got up and followed ENIAC to the door. But there was no sign of the robot, except for a diminishing whirlwind of dust in the middle of the corridor.

Something began to happen in Martin's brain....

Behind him, the telephone rang.

Martin heard himself gasp with pure terror. With a sudden, impossible, terrifying, absolute certainty he knew who was telephoning.

Assassins!

"Yes, Mr. Martin," said Tolliver Watt's butler to the telephone. "Miss Ashby is here. She is with Mr. Watt and Mr. St. Cyr at the moment, but I will give her your message. You are detained. And she is to call for you—where?"

"The broom-closet on the second floor of the Writers' Building," Martin said in a quavering voice. "It's the only one near a telephone with a long enough cord so I could take the phone in here with me. But I'm not at all certain that I'm safe. I don't like the looks of that broom on my left."

"Sir?"

"Are you sure you're Tolliver Watt's butler?" Martin demanded nervously.

"Quite sure, Mr.—eh—Mr. Martin."

"I am Mr. Martin," cried Martin with terrified defiance. "By all the laws of God and man, Mr. Martin I am and Mr. Martin I will remain, in spite of all attempts by rebellious dogs to depose me from my rightful place."

"Yes, sir. The broom-closet, you say, sir?"

"The broom-closet. Immediately. But swear not to tell another soul, no matter how much you're threatened. I'll protect you."

"Very well, sir. Is that all?"

"Yes. Tell Miss Ashby to hurry. Hang up now. The line may be tapped. I have enemies."

There was a click. Martin replaced his own receiver and furtively surveyed the broom-closet. He told himself that this was ridiculous. There was nothing to be afraid of, was there? True, the broom-closet's narrow walls were closing in upon him alarmingly, while the ceiling descended....

Panic-stricken, Martin emerged from the closet, took a long breath, and threw back his shoulders. "N-not a thing to be afraid of," he said. "Who's afraid?" Whistling, he began to stroll down the hall toward the staircase, but midway agoraphobia overcame him, and his nerve broke.

He ducked into his own office and sweated quietly in the dark until he had mustered up enough courage to turn on a lamp.

The Encyclopedia Britannica, in its glass-fronted cabinet, caught his eye. With noiseless haste, Martin secured ITALY to LORD and opened the volume at his desk. Something, obviously, was very, very wrong. The robot had said that Martin wasn't going to like being Ivan the Terrible, come to think of it. But was Martin wearing Ivan's character-matrix? Perhaps he'd got somebody else's matrix by mistake—that of some arrant coward. Or maybe the Mad Tsar of Russia had really been called Ivan the Terrified. Martin flipped the rustling pages nervously. Ivan, Ivan—here it was.

Son of Helena Glinska ... married Anastasia Zakharina-Koshkina ... private life unspeakably abominable ... memory astonishing, energy indefatigable, ungovernable fury—great natural ability, political foresight, anticipated the ideals of Peter the Great—Martin shook his head.

Then he caught his breath at the next line.

Ivan had lived in an atmosphere of apprehension, imagining that every man's hand was against him.

"Just like me," Martin murmured. "But—but there was more to Ivan than just cowardice. I don't understand."

"Differential," the robot had said, "depends on environment as much as on heredity. Though naturally Ivan wouldn't have had the Tsardom environment without his particular heredity."

Martin sucked in his breath sharply. Environment does make a difference. No doubt Ivan IV had been a fearful coward, but heredity plus environment had given Ivan the one great weapon that had enabled him to keep his cowardice a recessive trait.

Ivan the Terrible had been Tsar of all the Russias.

Give a coward a gun, and, while he doesn't stop being a coward, it won't show in the same way. He may act like a violent, aggressive tyrant instead. That, of course, was why Ivan

Comments (0)