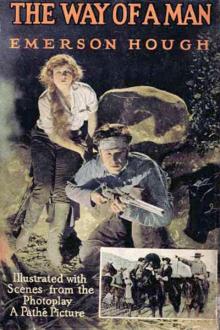

The Way of a Man, Emerson Hough [ebook reader macos .TXT] 📗

- Author: Emerson Hough

- Performer: -

Book online «The Way of a Man, Emerson Hough [ebook reader macos .TXT] 📗». Author Emerson Hough

Perhaps never was metamorphosis more complete than that which now took place. Shaking off detaining hands, Andrew Jackson sprang from our line, ran up to the fallen foe and in a frenzy of rage began to belabor and kick his body, winding up by catching him by the hair and actually dragging him some paces toward our firing line! An expression of absolute beatitude spread over the countenance of Mandy McGovern. She called out as though he were a young dog at his first fight. "Whoopee! Git to him, boy, git to him! Take him, boy! Whoopee!"

We got Andrew Jackson back into the ranks. His mother stepped to him and took him by the hand, as though for the first time she recognized him as a man.

"Now, boy, that's somethin' like." Presently she turned to me. "Some says it's in the Paw," she remarked. "I reckon it's some in the Maw; an' a leetle in the trainin'."

Cut up badly by our fire, the Sioux scattered and hugged the shelter of the river bank, beyond which they rode along the sand or in the shallow water, scrambling up the bank after they had gotten out of fire. Our men were firing less, frequently at the last of the line, who came swiftly down from the bluff and charged across behind us, sending in a scattering flight of arrows as they rode.

I looked about me now at the interior of our barricade. I saw Ellen Meriwether on her knees, lifting the shoulders of a wounded man who lay back, his hair dropping from his forehead, now gone bluish gray. She pulled him to the shelter of a wagon, where there had been drawn four others of the wounded. I saw tears falling from her eyes—saw the same pity on her face which I had noted once before when a wounded creature lay in her hands. I had been proud of Mandy McGovern. I was proud of Ellen Meriwether now. They were two generations of our women, the women of America, whom may God ever have in his keeping.

I say I had turned my head; but almost as I did so I felt a sudden jar as though some one had taken a board and struck me over the head with all his might. Then, as I slowly became aware, my head was utterly and entirely detached from my body, and went sailing off, deliberately, in front of me. I could see it going distinctly, and yet, oddly enough, I could also see a sudden change come on the face of the girl who was stooping before me, and who at the moment raised her eyes.

"It is strange," thought I, "but my head, thus detached, is going to pass directly above her, right there!"

Then I ceased to take interest in anything, and sank back into the arms of that from which we come, calmly taking bold of the hand of Mystery.

I awoke, I knew not how much later, into a world which at first had a certain warm comfort and languid luxury about it. Then I felt a sharp wrenching and a great pain in my neck, to which it seemed my departed head had, after all, returned. Stimulated by this pain, I turned and looked up into the face of Auberry. He stood frowning, holding in his hand a feathered arrow shaft of willow, grooved along its sides to let the blood run free, sinew-wrapped to hold its feathers tight—a typical arrow of the buffalo tribes. But, as I joined Auberry's gaze, I saw the arrow was headless! Dully I argued that, therefore, this head must be somewhere in my neck. I also saw that the sun was bright. I realized that there must have been a fight of some sort, but did not trouble to know whence the arrow had come to me, for my mind could grasp nothing more than simple things.

Thus I felt that my head was not uncomfortable, after all. I looked again, and saw that it rested on Ellen Meriwether's knees. She sat on the sand, gently stroking my forehead, pushing back the hair. She had turned my head so that the wound would not be pressed. It seemed to me that her voice sounded very far away and quiet.

"We are thinking," said she to me. I nodded as best I could. "Has anything happened?" I asked.

"They have gone," said she. "We whipped them." Her hand again lightly pressed my forehead.

I heard some one else say, behind me, "But we have nothing in the world—not even opium."

"True," said another voice, which I recognized as that of Orme; "but that's his one chance."

"What do you know about surgery?" asked the first voice, which I knew now was Belknap's.

"More than most doctors," was the answer, with a laugh. Their voices grew less distinguishable, but presently I heard Orme say, "Yes, I'm game to do it, if the man says so." Then he came and stooped down beside me.

"Mr. Cowles," said he, "you're rather badly off. That arrow head ought to come out, but the risk of going after it is very great. I am willing to do what you say. If you decide that you would like me to operate for it, I will do so. It's only right for me to tell you that it lies very close to the carotid artery, and that it will be an extraordinarily nice operation to get it out without—well, you know—"

I looked up into his face, that strange face which I was now beginning so well to know—the face of my enemy. I knew it was the face of a murderer, a man who would have no compunction at taking a human life.

My mind then was strangely clear. I saw his glance at the girl. I saw, as clearly as though he had told me, that this man was as deeply in love with Ellen Meriwether as I myself; that he would win her if he could; that his chance was as good as mine, even if we were both at our best. I knew there was nothing at which he would hesitate, unless some strange freak in his nature might influence him, such freaks as come to the lightning, to the wild beast slaying, changes for no reason ever known. Remorse, mercy, pity, I knew did not exist for him. But with a flash it came to my mind that this was all the better, if he must now serve as my surgeon.

He looked into my eye, and I returned his gaze, scorning to ask him not to take advantage of me, now that I was fallen. His own eye changed. It asked of me, as though he spoke: "Are you, then, game to the core? Shall I admire you and give you another chance, or shall I kill you now?" I say that I saw, felt, read all this in his mind. I looked up into his face, and said:

"You cannot kill me. I am not going to die. Go on. Soon, then."

A sort of sigh broke from his lips, as though he felt content. I do not think it was because he found his foe a worthy one. I do not think he considered me either as his foe or his friend or his patient. He was simply about to do something which would test his own nerve, his own resources, something which, if successful, would allow him to approve his own belief in himself. I say that this was merely sport for him. I knew he would not turn his hand to save my life; but also I knew that he would not cost it if that could be avoided, for that would mean disappointment to himself. What he did he did well. I said then to myself that I would pay him if he brought me through—pay him in some way.

Presently I heard them on the sand again, and I saw him come again and bend over me. All the instruments they could find had been a razor and a keen penknife; and all they could secure to staunch the blood was some water, nearly boiling. For forceps Orme had a pair of bullet molds, and these he cleansed as best he could by dipping them into the hot water.

"Cowles," he said, in a matter-of-fact voice, "I'm going after it. But now I tell you one thing frankly, it's life or death, and if you move your head it may mean death at once. That iron's lying against the big carotid artery. If it hasn't broken the artery wall, there's a ghost of a chance we can get it out safely, in which case you would probably pull through. I've got to open the neck and reach in. I'll do it as fast as I can. Now, I'm not going to think of you, and, gad!—if you can help it—please don't think of me."

Ellen Meriwether had not spoken. She still held my head in her lap.

"Are you game—can you do this, Miss Meriwether?" I heard Orme ask. She made no answer that I could hear, but must have nodded. I felt her hands press my head more tightly. I turned my face down and kissed her hand. "I will not move," I said.

I saw Orme's slender, naked wrist pass to my face and gently turn me into the position desired, with my face down and a little at one side, resting in her lap above her knees. Her skirt was already wet with the blood of the wound, and where my head lay it was damp with blood. Belknap took my hands and pulled them above my head, squatting beyond me. Between Orme's legs as he stooped I could see the dead body of a mule, I remember, and back of that the blue sky I and the sand dunes. Unknown to her, I kissed the hem of her garment; and then I said a short appeal to the Mystery.

I felt the entrance of the knife or razor blade, felt keenly the pain when the edge lifted and stretched the skin tight before the tough hide of my neck parted smoothly in a long line. Then I felt something warm settle under my cheek as I lay, and I felt a low shiver, whether of my body or that of the girl who held me I could not tell; but her hands were steady. I felt about me an infinite kindness and carefulness and pitying—oh, then I learned that life, after all, is not wholly war—that there is such a thing as fellow-suffering and loving kindness and a wish to aid others to survive in this hard fight of living; I knew that very well. But I did not gain

Comments (0)