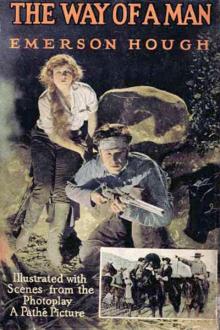

The Way of a Man, Emerson Hough [ebook reader macos .TXT] 📗

- Author: Emerson Hough

- Performer: -

Book online «The Way of a Man, Emerson Hough [ebook reader macos .TXT] 📗». Author Emerson Hough

The immediate pain of this long cutting which laid open my neck for some inches through the side muscles was less after the point of the blade went through and ceased to push forward. Deeper down I did not feel so much, until finally a gentle searching movement produced a jar strangely large, something which grated, and nearly sent all the world black again. I knew then that the knife was on the base of the arrow head; then I could feel it move softly and gently along the side of the arrow head—I could almost see it creep along in this delicate part of the work.

Then, all at once, I felt one hand removed from my neck. Orme, half rising from his stooping posture, but with the fingers of his left hand still at the wound, said: "Belknap, let go one of his hands. Just put your hand on this knife-blade, and feel that artery throb! Isn't it curious?"

I heard some muttered answer, but the grasp at my wrists did not relax. "Oh, it's all right now," calmly went on Orme, again stooping. "I thought you might be interested. It's all over now but pulling out the head."

I felt again a shiver run through the limbs of the girl. Perhaps she turned away her head, I do not know. I felt Orme's fingers spreading widely the sides of the wound along the neck, and the boring of the big headed bullet molds as they went down after a grip, their impact softened by the finger extended along the blade knife.

The throbbing artery whose location this man knew so well was protected. Gently feeling down, the tips of the mold got their grip at last, and an instant later I felt release from a certain stiff pressure which I had experienced in my neck. Relief came, then a dizziness and much pain. A hand patted me twice on the back of the neck.

"All right, my man," said Orme. "All over; and jolly well done, too, if I do say it myself!"

Belknap put his arm about me and helped me to sit up. I saw Orme holding out the stained arrow head, long and thin, in his fingers.

"Would you like it?" he said.

"Yes," said I, grinning. And I confess I have it now somewhere about my house. I doubt if few souvenirs exist to remind one of a scene exactly similar.

The girl now kept cloths wrung from the hot water on my neck. I thanked them all as best I could. "I say, you men," remarked Mandy McGovern, coming up with a cob-stoppered flask in her hand, half filled with a pale yellow-white fluid, "ain't it about time for some of that thar anarthestic I heerd you all talking about a while ago?"

"I shouldn't wonder," said Orme. "The stitching hurts about as much as anything. Auberry, can't you find me a bit of sinew somewhere, and perhaps a needle of some sort?"

A vast dizziness and a throbbing of the head remained after they were quite done with me, but something of this left me when finally I sat leaning back against the wagon body and looked about me. There were straight, motionless figures lying under the blankets in the shade, and under other blankets were men who writhed and moaned. Belknap passed about the place, graver and apparently years older than at the beginning of this, his first experience in the field. He put out burial parties at once. A few of the Sioux, including the one on whom Andrew Jackson McGovern had vented his new-found spleen, were covered scantily where they lay. Our own dead were removed to the edge of the bluff; and so more headstones, simple and rude, went to line the great pathway into the West.

Again Ellen Meriwether came and sat by me. She had now removed the gray traveling gown, for reasons which I could guess, and her costume might have been taken from a collector's chest rather than a woman's wardrobe. All at once we seemed, all of us, to be blending with these surroundings, becoming savage as these other savages. It might almost have been a savage woman who came to me.

Her skirt was short; made of white tanned antelope leather. Above it fell the ragged edges of a native tunic or shirt of yellow buck, ornamented with elk teeth, embroidered in stained quills. Her feet still wore a white woman's shoes, although the short skirt was enforced by native leggins, beaded and becylindered in metals so that she tinkled as the walked. Her hair, now becoming yellower and more sunburned at the ends, was piled under her felt hat, and the modishness of long cylindrical curls was quite forgot. The brown of her cheeks, already strongly sunburned, showed in strange contrast to the snowy white of her neck, now exposed by the low neck aperture of the Indian tunic. Her gloves, still fairly fresh, she wore tucked through her belt, army fashion. I could see the red heart still, embroidered on the cuff!

She came and sat down beside me on the ground, I say, and spoke to me. I could not help reflecting how she was reverting, becoming savage. I thought this—but in my heart I knew she was not savage as myself.

"How are you coming on?" she said. "You sit up nicely—"

"Yes, and can stand, or walk, or ride," I added.

Her brown eyes were turned full on me. In the sunlight I could see the dark specks in their depths. I could see every shade of tan on her face.

"You are not to be foolish," she said.

"You stand all this nobly," I commented presently.

"Ah, you men—I love you, you men!" She said it suddenly and with perfect sincerity. "I love you all—you are so strong, so full of the desire to live, to win. It is wonderful, wonderful! Just look at those poor boys there—some of them are dying, almost, but they won't whimper. It is wonderful."

"It is the Plains," I said. "They have simply learned how little a thing is life."

"Yet it is sweet," she said.

"But for you, I see that you have changed again."

She spread her leather skirt down with her hands, as though to make it longer, and looked contemplatively at the fringed leggins below.

"You were four different women," I mused, "and now you are another, quite another."

At this she frowned a bit, and rose. "You are not to talk," she said, "nor to think that you are well; because you are not. I must go and see the others."

I lay back against the wagon bed, wondering in which garb she had been most beautiful—the filmy ball dress and the mocking mask, the gray gown and veil of the day after, the thin drapery of her hasty flight in the night, her half conventional costume of the day before—or this, the garb of some primeval woman. I knew I could never forget her again. The thought gave me pain, and perhaps this showed on my face, for my eyes followed her so that presently she turned and came back to me.

"Does the wound hurt you?" she asked. "Are you in pain?"

"Yes, Ellen Meriwether," I said, "I am in pain. I am in very great pain."

"Oh," she cried, "I am sorry! What can we do? What do you wish? But perhaps it will not be so bad after a while—it will be over soon."

"No, Ellen Meriwether," I said, "it will not be over soon. It will not go away at all."

We lay in our hot camp on the sandy valley for some days, and buried two more of our men who finally succumbed to their wounds. Gloom sat on us all, for fever now raged among our wounded. Pests of flies by day and mosquitoes by night became almost unbearable. The sun blistered us, the night froze us. Still not a sign of any white-topped wagon from the east, nor any dust-cloud of troopers from the west served to break the monotony of the shimmering waste that lay about us on every hand. We were growing gaunt now and haggard; but still we lay, waiting for our men to grow strong enough to travel, or to lose all strength and so be laid away.

We had no touch with the civilization of the outer world. At that time the first threads of the white man's occupancy were just beginning to cross the midway deserts. Near by our camp ran the recently erected line of telegraph, its shining cedar poles, stripped of their bark, offering wonder for savage and civilized man alike, for hundreds of miles across an uninhabited country. We could see the poles rubbed smooth at their base by the shoulders of the buffalo. Here and there a little tuft of hair clung to some untrimmed knot. High up in some of the naked poles we could see still sticking, the iron shod arrows of contemptuous tribesmen, who had thus sought to assail the "great medicine" of the white man. We heard the wires above us humming mysteriously in the wind, but if they bore messages east or west, we might not read them, nor might we send any message of our own.

At times old Auberry growled at this new feature of the landscape. "That was not here when I first came West," he said, "and I don't like its looks. The old ways were good enough. Now they are even talkin' of runnin' a railroad up the valley—as though horses couldn't carry in everything the West needs or bring out everything the East may want. No, the old ways were good enough for me."

Orme smiled at the old man.

"None the less," said he, "you will see the day before long, when not one railroad, but many, will cross these plains. As for the telegraph, if only we had a way of tapping these wires, we might find it extremely useful to us all right now."

"The old ways were good enough," insisted Auberry. "As fur telegraphin', it ain't new on these plains. The Injuns could always telegraph, and they didn't need no poles nor wires. The Sioux may be at both ends of this bend, for all we know. They may have cleaned up all the wagons coming west. They have planned for a general wipin' out of the whites, and you can be plumb certain that what has happened here is knowed all acrost this country to-day, clean to the big bend of the Missouri, and on the Yellowstone, and west to the Rockies."

"How could that be?" asked Orme, suddenly, with interest. "You talk as if there were something in this country like the old 'secret mail' of East India, where I once lived."

"I don't know what you mean by that," said Auberry, "but I do know that the Injuns in this country have ways of talkin' at long range. Why, onct a bunch of us had five men killed up on the Powder River by the Crows. That was ten o'clock in the morning. By two in the afternoon everyone in the Crow village, two hundred miles away, knowed all about the fight—how many whites was killed, how many Injuns—the whole shootin'-match. How they done it, I don't know, but they shore done it. Any Western man knows that much about Injun ways."

"That is rather extraordinary," commented Orme.

"Nothin' extraordinary about it," said Auberry, "it's just common. Maybe they done it by lookin'-glasses and smokes—fact is, I know that's one way they use a heap. But they've got other ways of talkin'. Looks like a Injun could set right down on a hill, and think good and hard, and some other Injun a hundred miles away'd know what he was thinkin' about. You talk about a prairie fire runnin' fast—it ain't nothin' to the way news travels amongst the tribes."

Belknap expressed his contempt

Comments (0)