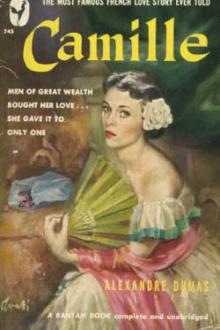

Camille, fils Alexandre Dumas [golden son ebook txt] 📗

- Author: fils Alexandre Dumas

- Performer: -

Book online «Camille, fils Alexandre Dumas [golden son ebook txt] 📗». Author fils Alexandre Dumas

And Prudence opened the drawer and showed me the papers.

“Ah, you think,” she continued, with the insistence of a woman who can say, I was right after all, “ah, you think it is enough to be in love, and to go into the country and lead a dreamy, pastoral life. No, my friend, no. By the side of that ideal life, there is a material life, and the purest resolutions are held to earth by threads which seem slight enough, but which are of iron, not easily to be broken. If Marguerite has not been unfaithful to you twenty times, it is because she has an exceptional nature. It is not my fault for not advising her to, for I couldn’t bear to see the poor girl stripping herself of everything. She wouldn’t; she replied that she loved you, and she wouldn’t be unfaithful to you for anything in the world. All that is very pretty, very poetical, but one can’t pay one’s creditors in that coin, and now she can’t free herself from debt, unless she can raise thirty thousand francs.”

“All right, I will provide that amount.”

“You will borrow it?”

“Good heavens! Why, yes!”

“A fine thing that will be to do; you will fall out with your father, cripple your resources, and one doesn’t find thirty thousand francs from one day to another. Believe me, my dear Armand, I know women better than you do; do not commit this folly; you will be sorry for it one day. Be reasonable. I don’t advise you to leave Marguerite, but live with her as you did at the beginning. Let her find the means to get out of this difficulty. The duke will come back in a little while. The Comte de N., if she would take him, he told me yesterday even, would pay all her debts, and give her four or five thousand francs a month. He has two hundred thousand a year. It would be a position for her, while you will certainly be obliged to leave her. Don’t wait till you are ruined, especially as the Comte de N. is a fool, and nothing would prevent your still being Marguerite’s lover. She would cry a little at the beginning, but she would come to accustom herself to it, and you would thank me one day for what you had done. Imagine that Marguerite is married, and deceive the husband; that is all. I have already told you all this once, only at that time it was merely advice, and now it is almost a necessity.”

What Prudence said was cruelly true.

“This is how it is,” she went on, putting away the papers she had just shown me; “women like Marguerite always foresee that some one will love them, never that they will love; otherwise they would put aside money, and at thirty they could afford the luxury of having a lover for nothing. If I had only known once what I know now! In short, say nothing to Marguerite, and bring her back to Paris. You have lived with her alone for four or five months; that is quite enough. Shut your eyes now; that is all that any one asks of you. At the end of a fortnight she will take the Comte de N., and she will save up during the winter, and next summer you will begin over again. That is how things are done, my dear fellow!”

And Prudence appeared to be enchanted with her advice, which I refused indignantly.

Not only my love and my dignity would not let me act thus, but I was certain that, feeling as she did now, Marguerite would die rather than accept another lover.

“Enough joking,” I said to Prudence; “tell me exactly how much Marguerite is in need of.”

“I have told you: thirty thousand francs.”

“And when does she require this sum?”

“Before the end of two months.”

“She shall have it.”

Prudence shrugged her shoulders.

“I will give it to you,” I continued, “but you must swear to me that you will not tell Marguerite that I have given it to you.”

“Don’t be afraid.”

“And if she sends you anything else to sell or pawn, let me know.”

“There is no danger. She has nothing left.”

I went straight to my own house to see if there were any letters from my father. There were four.

In his first three letters my father inquired the cause of my silence; in the last he allowed me to see that he had heard of my change of life, and informed me that he was about to come and see me.

I have always had a great respect and a sincere affection for my father. I replied that I had been travelling for a short time, and begged him to let me know beforehand what day he would arrive, so that I could be there to meet him.

I gave my servant my address in the country, telling him to bring me the first letter that came with the postmark of C., then I returned to Bougival.

Marguerite was waiting for me at the garden gate. She looked at me anxiously. Throwing her arms round my neck, she said to me: “Have you seen Prudence?”

“No.”

“You were a long time in Paris.”

“I found letters from my father to which I had to reply.”

A few minutes afterward Nanine entered, all out of breath. Marguerite rose and talked with her in whispers. When Nanine had gone out Marguerite sat down by me again and said, taking my hand:

“Why did you deceive me? You went to see Prudence.”

“Who told you?”

“Nanine.”

“And how did she know?”

“She followed you.”

“You told her to follow me?”

“Yes. I thought that you must have had a very strong motive for going to Paris, after not leaving me for four months. I was afraid that something might happen to you, or that you were perhaps going to see another woman.”

“Child!”

“Now I am relieved. I know what you have done, but I don’t yet know what you have been told.”

I showed Marguerite my father’s letters.

“That is not what I am asking you about. What I want to know is why you went to see Prudence.”

“To see her.”

“That’s a lie, my friend.”

“Well, I went to ask her if the horse was any better, and if she wanted your shawl and your jewels any longer.”

Marguerite blushed, but did not answer.

“And,” I continued, “I learned what you had done with your horses, shawls, and jewels.”

“And you are vexed?”

“I am vexed that it never occurred to you to ask me for what you were in want of.”

“In a liaison like ours, if the woman has any sense of dignity at all, she ought to make every possible sacrifice rather than ask her lover for money and so give a venal character to her love. You love me, I am sure, but you do not know on how slight a thread depends the love one has for a woman like me. Who knows? Perhaps some day when you were bored or worried you would fancy you saw a carefully concerted plan in our liaison. Prudence is a chatterbox. What need had I of the horses? It was an economy to sell them. I don’t use them and I don’t spend anything on their keep; if you love me, I ask nothing more, and you will love me just as much without horses, or shawls, or diamonds.”

All that was said so naturally that the tears came to my eyes as I listened.

“But, my good Marguerite,” I replied, pressing her hands lovingly, “you knew that one day I should discover the sacrifice you had made, and that the moment I discovered it I should allow it no longer.”

“But why?”

“Because, my dear child, I can not allow your affection for me to deprive you of even a trinket. I too should not like you to be able, in a moment when you were bored or worried, to think that if you were living with somebody else those moments would not exist; and to repent, if only for a minute, of living with me. In a few days your horses, your diamonds, and your shawls shall be returned to you. They are as necessary to you as air is to life, and it may be absurd, but I like you better showy than simple.”

“Then you no longer love me.”

“Foolish creature!”

“If you loved me, you would let me love you my own way; on the contrary, you persist in only seeing in me a woman to whom luxury is indispensable, and whom you think you are always obliged to pay. You are ashamed to accept the proof of my love. In spite of yourself, you think of leaving me some day, and you want to put your disinterestedness beyond risk of suspicion. You are right, my friend, but I had better hopes.”

And Marguerite made a motion to rise; I held her, and said to her:

“I want you to be happy and to have nothing to reproach me for, that is all.”

“And we are going to be separated!”

“Why, Marguerite, who can separate us?” I cried.

“You, who will not let me take you on your own level, but insist on taking me on mine; you, who wish me to keep the luxury in the midst of which I have lived, and so keep the moral distance which separates us; you, who do not believe that my affection is sufficiently disinterested to share with me what you have, though we could live happily enough on it together, and would rather ruin yourself, because you are still bound by a foolish prejudice. Do you really think that I could compare a carriage and diamonds with your love? Do you think that my real happiness lies in the trifles that mean so much when one has nothing to love, but which become trifling indeed when one has? You will pay my debts, realize your estate, and then keep me? How long will that last? Two or three months, and then it will be too late to live the life I propose, for then you will have to take everything from me, and that is what a man of honour can not do; while now you have eight or ten thousand francs a year, on which we should be able to live. I will sell the rest of what I do not want, and with this alone I will make two thousand francs a year. We will take a nice little flat in which we can both live. In the summer we will go into the country, not to a house like this, but to a house just big enough for two people. You are independent, I am free, we are young; in heaven’s name, Armand, do not drive me back into the life I

Comments (0)