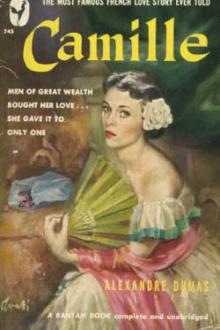

Camille, fils Alexandre Dumas [golden son ebook txt] 📗

- Author: fils Alexandre Dumas

- Performer: -

Book online «Camille, fils Alexandre Dumas [golden son ebook txt] 📗». Author fils Alexandre Dumas

I could not answer. Tears of gratitude and love filled my eyes, and I flung myself into Marguerite’s arms.

“I wanted,” she continued, “to arrange everything without telling you, pay all my debts, and take a new flat. In October we should have been back in Paris, and all would have come out; but since Prudence has told you all, you will have to agree beforehand, instead of agreeing afterward. Do you love me enough for that?”

It was impossible to resist such devotion. I kissed her hands ardently, and said:

“I will do whatever you wish.”

It was agreed that we should do as she had planned. Thereupon, she went wild with delight; danced, sang, amused herself with calling up pictures of her new flat in all its simplicity, and began to consult me as to its position and arrangement. I saw how happy and proud she was of this resolution, which seemed as if it would bring us into closer and closer relationship, and I resolved to do my own share. In an instant I decided the whole course of my life. I put my affairs in order, and made over to Marguerite the income which had come to me from my mother, and which seemed little enough in return for the sacrifice which I was accepting. There remained the five thousand francs a year from my father; and, whatever happened, I had always enough to live on. I did not tell Marguerite what I had done, certain as I was that she would refuse the gift. This income came from a mortgage of sixty thousand francs on a house that I had never even seen. All that I knew was that every three months my father’s solicitor, an old friend of the family, handed over to me seven hundred and fifty francs in return for my receipt.

The day when Marguerite and I came to Paris to look for a flat, I went to this solicitor and asked him what had to be done in order to make over this income to another person. The good man imagined I was ruined, and questioned me as to the cause of my decision. As I knew that I should be obliged, sooner or later, to say in whose favour I made this transfer, I thought it best to tell him the truth at once. He made none of the objections that his position as friend and solicitor authorized him to make, and assured me that he would arrange the whole affair in the best way possible. Naturally, I begged him to employ the greatest discretion in regard to my father, and on leaving him I rejoined Marguerite, who was waiting for me at Julie Duprat’s, where she had gone in preference to going to listen to the moralizings of Prudence.

We began to look out for flats. All those that we saw seemed to Marguerite too dear, and to me too simple. However, we finally found, in one of the quietest parts of Paris, a little house, isolated from the main part of the building. Behind this little house was a charming garden, surrounded by walls high enough to screen us from our neighbours, and low enough not to shut off our own view. It was better than our expectations.

While I went to give notice at my own flat, Marguerite went to see a business agent, who, she told me, had already done for one of her friends exactly what she wanted him to do for her. She came on to the Rue de Provence in a state of great delight. The man had promised to pay all her debts, to give her a receipt for the amount, and to hand over to her twenty thousand francs, in return for the whole of her furniture. You have seen by the amount taken at the sale that this honest man would have gained thirty thousand francs out of his client.

We went back joyously to Bougival, talking over our projects for the future, which, thanks to our heedlessness, and especially to our love, we saw in the rosiest light.

A week later, as we were having lunch, Nanine came to tell us that my servant was asking for me. “Let him come in,” I said.

“Sir,” said he, “your father has arrived in Paris, and begs you to return at once to your rooms, where he is waiting for you.”

This piece of news was the most natural thing in the world, yet, as we heard it, Marguerite and I looked at one another. We foresaw trouble. Before she had spoken a word, I replied to her thought, and, taking her hand, I said, “Fear nothing.”

“Come back as soon as possible,” whispered Marguerite, embracing me; “I will wait for you at the window.”

I sent on Joseph to tell my father that I was on my way. Two hours later I was at the Rue de Provence.

My father was seated in my room in his dressing-gown; he was writing, and I saw at once, by the way in which he raised his eyes to me when I came in, that there was going to be a serious discussion. I went up to him, all the same, as if I had seen nothing in his face, embraced him, and said:

“When did you come, father?”

“Last night.”

“Did you come straight here, as usual?”

“Yes.”

“I am very sorry not to have been here to receive you.”

I expected that the sermon which my father’s cold face threatened would begin at once; but he said nothing, sealed the letter which he had just written, and gave it to Joseph to post.

When we were alone, my father rose, and leaning against the mantelpiece, said to me:

“My dear Armand, we have serious matters to discuss.”

“I am listening, father.”

“You promise me to be frank?”

“Am I not accustomed to be so?”

“Is it not true that you are living with a woman called Marguerite Gautier?”

“Yes.”

“Do you know what this woman was?”

“A kept woman.”

“And it is for her that you have forgotten to come and see your sister and me this year?”

“Yes, father, I admit it.”

“You are very much in love with this woman?”

“You see it, father, since she has made me fail in duty toward you, for which I humbly ask your forgiveness to-day.”

My father, no doubt, was not expecting such categorical answers, for he seemed to reflect a moment, and then said to me:

“You have, of course, realized that you can not always live like that?”

“I fear so, father, but I have not realized it.”

“But you must realize,” continued my father, in a dryer tone, “that I, at all events, should not permit it.”

“I have said to myself that as long as I did nothing contrary to the respect which I owe to the traditional probity of the family I could live as I am living, and this has reassured me somewhat in regard to the fears I have had.”

Passions are formidable enemies to sentiment. I was prepared for every struggle, even with my father, in order that I might keep Marguerite.

“Then, the moment is come when you must live otherwise.”

“Why, father?”

“Because you are doing things which outrage the respect that you imagine you have for your family.”

“I don’t follow your meaning.”

“I will explain it to you. Have a mistress if you will; pay her as a man of honour is bound to pay the woman whom he keeps, by all means; but that you should come to forget the most sacred things for her, that you should let the report of your scandalous life reach my quiet countryside, and set a blot on the honourable name that I have given you, it can not, it shall not be.”

“Permit me to tell you, father, that those who have given you information about me have been ill-informed. I am the lover of Mlle. Gautier; I live with her; it is the most natural thing in the world. I do not give Mlle. Gautier the name you have given me; I spend on her account what my means allow me to spend; I have no debts; and, in short, I am not in a position which authorizes a father to say to his son what you have just said to me.”

“A father is always authorized to rescue his son out of evil paths. You have not done any harm yet, but you will do it.”

“Father!”

“Sir, I know more of life than you do. There are no entirely pure sentiments except in perfectly chaste women. Every Manon can have her own Des Grieux, and times are changed. It would be useless for the world to grow older if it did not correct its ways. You will leave your mistress.”

“I am very sorry to disobey you, father, but it is impossible.”

“I will compel you to do so.”

“Unfortunately, father, there no longer exists a Sainte Marguerite to which courtesans can be sent, and, even if there were, I would follow Mlle. Gautier if you succeeded in having her sent there. What would you have? Perhaps am in the wrong, but I can only be happy as long as I am the lover of this woman.”

“Come, Armand, open your eyes. Recognise that it is your father who speaks to you, your father who has always loved you, and who only desires your happiness. Is it honourable for you to live like husband and wife with a woman whom everybody has had?”

“What does it matter, father, if no one will any more? What does it matter, if this woman loves me, if her whole life is changed through the love which she has for me and the love which I have for her? What does it matter, if she has become a different woman?”

“Do you think, then, sir, that the mission of a man of honour is to go about converting lost women? Do you think that God has given such a grotesque aim to life, and that the heart should have any room for enthusiasm of that kind? What will be the end of this marvellous cure, and what will you think of what you are saying to-day by the time you are forty? You will laugh at this love of yours, if you can still laugh, and if it has not left too serious a trace in your past. What would you be now if your father had had your ideas and had given up his life to every impulse of this kind, instead of rooting himself firmly in convictions of honour and steadfastness? Think it over, Armand, and do not talk any more such absurdities. Come, leave this woman; your father entreats you.”

I answered nothing.

“Armand,” continued my father, “in the name of your sainted mother, abandon this life, which you will forget more easily than you think. You are tied to it by an impossible theory. You are twenty-four; think of the future. You can not always love this woman, who also can not always love you. You both exaggerate your love. You put an end to your whole career. One step further, and you will no longer be able to leave the path you have chosen, and you will suffer all your life for what you have done in your youth. Leave Paris. Come and stay for a month or two with your sister and me. Rest in our quiet family affection will soon heal you of this fever, for it is nothing else. Meanwhile, your mistress will console herself; she will take another lover; and when you see what it is for which you have all but broken with your father, and all but lost his

Comments (0)