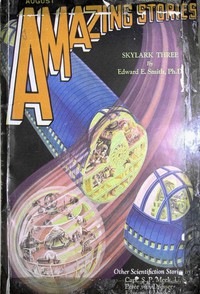

Skylark Three, E. E. Smith [libby ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: E. E. Smith

Book online «Skylark Three, E. E. Smith [libby ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author E. E. Smith

As the minute of departure drew near, the feeling of tension aboard the cruiser increased and vigilance was raised to the maximum. None of the passengers had been allowed senders of any description, and now even the hair-line beams guiding the airboats were cut off, and received only when the proper code signal was heard. The doors were shut, no one was allowed outside, and everything was held in readiness for instant flight at the least alarm. Finally a scientist and his family arrived from the opposite side of the planet—the last members of the organization—and, twenty-seven minutes after Ravindau had flashed his signal, the prow of that mighty space-ship reared toward the perpendicular, poising its massive length at the predetermined angle. There it halted momentarily, then disappeared utterly, only a vast column of tortured and shattered vegetation, torn from the ground and carried for miles upward into the air by the vacuum of its wake, remaining to indicate the path taken by the flying projectile.

Hour after hour the Fenachrone vessel bored on, with its frightful and ever-increasing velocity, through the ever-thinning stars, but it was not until the last[Pg 622] star had been passed, until everything before them was entirely devoid of light, and until the Galaxy behind them began to take on a well-defined lenticular aspect, that Ravindau would consent to leave the controls and to seek his hard-earned rest.

Day after day and week after week went by, and the Fenachrone vessel still held the rate of motion with which she had started out. Ravindau and Fenimol sat in the control cabin, staring out through the visiplates, abstracted. There was no need of staring, and they were not really looking, for there was nothing at which to look. Outside the transparent metal hull of that monster of the trackless void, there was nothing visible. The Galaxy of which our Earth is an infinitesimal mote, the Galaxy which former astronomers considered the Universe, was so far behind that its immeasurable diameter was too small to affect the vision of the unaided eye. Other Galaxies lay at even greater distances away on either side. The Galaxy toward which they were making their stupendous flight was as yet untold millions of light-years distant. Nothing was visible—before their gaze stretched an infinity of emptiness. No stars, no nebulæ, no meteoric matter, nor even the smallest particle of cosmic dust—absolutely empty space. Absolute vacuum and absolute zero. Absolute nothingness—a concept intrinsically impossible for the most highly trained human mind to grasp.

Conscienceless and heartless monstrosities though they both were, by heredity and training, the immensity of the appalling lack of anything tangible oppressed them. Ravindau was stern and serious, Fenimol moody. Finally the latter spoke.

"It would be endurable if we knew what had happened, or if we ever could know definitely, one way or the other, whether all this was necessary."

"We shall know, general, definitely. I am certain in my own mind, but after a time, when we have settled upon our new home and when the Overlord shall have relaxed his vigilance, you shall come back to the solar system of the Fenachrone in this vessel or a similar one. I know what you shall find—but the trip shall be made, and you shall yourself see what was once our home planet, a seething sun, second only in brilliance to the parent sun about which she shall still be revolving."

"Are we safe, even now—what of possible pursuit?" asked Fenimol, and the monstrous, flame-shot wells of black that were Ravindau's eyes almost emitted tangible fires as he made reply:

"We are far from safe, but we grow stronger minute by minute. Fifty of the greatest minds our world has ever known have been working from the moment of our departure upon a line of investigation suggested to me by certain things my instruments recorded during the visit of the self-styled Overlord. I cannot say anything yet: even to you—except that the Day of Conquest may not be so far in the future as we have supposed."

CHAPTER XIV Interstellar Extermination"I hate to leave this meeting—it's great stuff" remarked Seaton as he flashed down to the torpedo room at Fenor's command to send recall messages to all outlying vessels, "but this machine isn't designed to let me be in more than two places at once. Wish it were—maybe after this fracas is over we'll be able to incorporate something like that into it."

The chief operator touched a lever and the chair upon which he sat, with all its control panels, slid rapidly across the floor toward an apparently blank wall. As he reached it, a port opened a metal scroll appeared, containing the numbers and last reported positions of all Fenachrone vessels outside the detector zone, and a vast magazine of torpedoes came up through the floor, with an automatic loader to place a torpedo under the operator's hand the instant its predecessor had been launched.

"Get Peg here quick, Mart—we need a stenographer. Till she gets here, see what you can do in getting those first numbers before they roll off the end of the scroll. No, hold it—as you were! I've got controls enough to put the whole thing on a recorder, so we can study it at our leisure."

Haste was indeed necessary for the operator worked with uncanny quickness of hand. One fleeting glance at the scroll, a lightning adjustment of dials in the torpedo, a touch upon a tiny button, and a messenger was upon its way. But quick as he was, Seaton's flying fingers kept up with him, and before each torpedo disappeared through the ether gate there was fastened upon it a fifth-order tracer ray that would never leave it until the force had been disconnected at the gigantic control board of the Norlaminian projector. One flying minute passed during which seventy torpedoes had been launched, before Seaton spoke.

"Wonder how many ships they've got out, anyway? Didn't get any idea from the brain-record. Anyway, Rovol, it might be a sound idea for you to install me some more tracer rays on this board, I've got only a couple of hundred, and that may not be enough—and I've got both hands full."

Rovol seated himself beside the younger man, like one organist joining another at the console of a tremendous organ. Seaton's nimble fingers would flash here and there, depressing keys and manipulating controls until he had exactly the required combination of forces centered upon the torpedo next to issue. He then would press a tiny switch and upon a panel full of red-topped, numbered plungers; the one next in series would drive home, transferring to itself the assembled beam and releasing the keys for the assembly of other forces. Rovol's fingers were also flying, but the forces he directed were seizing and shaping material, as well as other forces. The Norlaminian physicist, set up one integral, stepped upon a pedal, and a new red-topped stop precisely like the others and numbered in order, appeared as though by magic upon the panel at Seaton's left hand. Rovol then leaned back in his seat—but the red-topped stops continued to appear, at the rate of exactly seventy per minute, upon the panel, which increased in width sufficiently to accommodate another row as soon as a row was completed.

Rovol bent a quizzical glance upon the younger scientist, who blushed a fiery red, rapidly set up another integral, then also leaned back in his place, while his face burned deeper than before.

"That is better, son. Never forget that it is a waste of energy to do the same thing twice with your hands and that if you know precisely what is to be done, you need not do it with your hands at all. Forces are tireless, and they neither slip nor make mistakes."[Pg 623]

"Thanks, Rovol—I'll bet this lesson will make it stick in my mind, too."

"You are not thoroughly accustomed to using all your knowledge as yet. That will come with practice, however, and in a few weeks you will be as thoroughly at home with forces as I am."

"Hope so, Chief, but it looks like a tall order to me."

Finally the last torpedo was dispatched, the tube closed, and Seaton moved the projection back up into the council chamber, finding it empty.

"Well, the conference is over—besides, we've got more important fish to fry. War has been declared, on both sides, and we've got to get busy. They've got nine hundred and six vessels out, and every one of them has got to go to Davy Jones' locker before we can sleep sound of nights. My first job'll have to be untangling those nine oh six forces, getting lines on each one of them, and seeing if I can project straight enough to find the ships before the torpedoes overtake them. Mart, you and Orlon, the astronomer, had better dope out the last reported positions of each of those vessels, so we'll know about where to hunt for them. Rovol, you might send out a detector screen a few light years in diameter, to be sure none of them slips a fast one over on us. By starting it right here and expanding it gradually, you can be sure that no Fenachrone is inside it. Then we'll find a hunk of copper on that planet somewhere, plate it with some of their own 'X' metal, and blow them into Kingdom Come."

"May I venture a suggestion?" asked Drasnik, the First of Psychology.

"Absolutely—nothing you've said so far has been idle chatter."

"You know, of course, that there are real scientists among the Fenachrone; and you yourself have suggested that while they cannot penetrate the zone of force nor use fifth-order rays, yet they might know about them in theory, might even be able to know when they were being used—detect them, in other words. Let us assume that such a scientist did detect your rays while you were there a short time ago. What would he do?"

"Search me.... I bite, what would he do?"

"He might do any one of several things, but if I read their nature aright, such a one would gather up a few men and women—as many as he could—and migrate to another planet. For he would of course grasp instantly the fact that you had used fifth-order rays as carrier waves, and would be able to deduce your ability to destroy. He would also realize that in the brief time allowed him, he could not hope to learn to control those unknown forces; and with his terribly savage and vengeful nature and intense pride of race, he would take every possible step both to perpetuate his race and to obtain revenge. Am I right?"

Seaton swung to his controls savagely, and manipulated dials and keys rapidly.

"Right as rain, Drasnik. There—I've thrown around them a fifth-order detector screen, that they can't possibly neutralize. Anything that goes out through it will have a tracer slapped onto it. But say, it's been half an hour since war was declared—suppose we're too late? Maybe some of them have got away already, and if one couple of 'em has beat us to it, we'll have the whole thing to do over again a thousand years or so from now. You've got the massive intellect, Drasnik. What can we do about it? We can't throw a detector screen all over the Galaxy."

"I would suggest that since you have now guarded against further exodus, it is necessary to destroy the planet for a time. Rovol and his co-workers have the other projector nearly done. Let them project me to the world of the Fenachrone, where I shall conduct a thorough mental investigation. By the time you have taken care of the raiding vessels, I believe that I shall have been able to learn everything we need to know."

"Fine—hop to it, and may there be lots of bubbles in your think-tank. Anybody else know of any other loop-holes I've left open?"

No other suggestions were made, and each man bent to his particular task. Crane at the star-chart of the Galaxy and Orlon at the Fenachrone operator's dispatching scroll rapidly worked out the approximate positions of the Fenachrone vessels, and marked them with tiny green lights in a vast model of the Galaxy which they had already caused forces to erect in the air of the projector's base. It was soon learned that a few of the ships were exploring quite close to their home system; so close that the torpedoes, with their unthinkable acceleration, would reach them within a few hours. Ascertaining the stop-number of the tracer ray upon the torpedo which should first reach its destination, Seaton followed it from the stop upon his panel out to the flying messenger. Now moving with a velocity many times that of light, it was, of course, invisible to direct vision; but to the light waves heterodyned upon the fifth-order projector rays, it was as plainly visible as though it were stationary. Lining up the path of the projectile accurately, he then projected himself forward in that exact line, with a flat detector-screen thrown out for half a light year upon each side of him. Setting the controls, he flashed ahead, the detector stopping him the instant that the invisible barrier encountered

Comments (0)