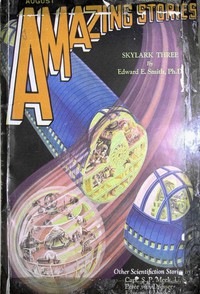

Skylark Three, E. E. Smith [libby ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: E. E. Smith

Book online «Skylark Three, E. E. Smith [libby ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author E. E. Smith

The Fenachrone ship, a thousand feet long and more than a hundred feet in diameter, was tearing through space toward a brilliant blue-white star. Her crew were at battle stations, her navigating officers peering intently into the operating visiplates, all oblivious to the fact that a stranger stood in their very midst.

"Well, here's the first one, gang," said Seaton, "I hate like sin to do this—it's altogether too much like pushing baby chickens into a creek to suit me, but it's a dirty job that's got to be done."

As one man, Orlon and the other remaining Norlaminians leaped out of the projector and floated to the ground below.

"I expected that," remarked Seaton. "They can't even think of a thing like this without getting the blue willies—I don't blame them much, at that. How about you, Carfon? You can be excused if you like."

"I want to watch those forces at work. I do not enjoy destruction, but like you, I can make myself endure it."

Dunark, the fierce and bloodthirsty Osnomian prince, leaped to his feet, his eyes flashing.

"That's one thing I never could get about you, Dick!" he exclaimed in English. "How a man with your brains can be so soft—so sloppily sentimental, gets clear past me. You remind me of a bowl of mush—you wade[Pg 624] around in slush clear to your ears. Faugh! It's their lives or ours! Tell me what button to push and I'll be only too glad to push it. I wanted to blow up Urvania and you wouldn't let me; I haven't killed an enemy for ages, and that's my trade. Cut out the sob-sister act and for Cat's sake, let's get busy!"

"'At-a-boy, Dunark! That's tellin' 'im! But it's all right with me—I'll be glad to let you do it. When I say 'shoot' throw in that plunger there—number sixty-three."

Seaton manipulated controls until two electrodes of force were clamped in place, one at either end of the huge power-bar of the enemy vessel; adjusted rheostats and forces to send a disintegrating current through that massive copper cylinder, and gave the word. Dunark threw in the switch with a vicious thrust, as though it were an actual sword which he was thrusting through the vitals of one of the awesome crew, and the very Universe exploded around them—exploded into one mad, searing coruscation of blinding, dazzling light as the gigantic cylinder of copper resolved itself instantaneously into the pure energy from which its metal originally had come into being.

Seaton and Dunark staggered back from the visiplates, blinded by the intolerable glare of light, and even Crane, working at his model of the galaxy, blinked at the intensity of the radiation. Many minutes passed before the two men could see through their tortured eyes.

"Zowie! That was fierce!" exclaimed Seaton, when a slowly-returning perception of things other than dizzy spirals and balls of flame assured him that his eyesight was not permanently gone. "It's nothing but my own fool carelessness, too. I should have known that with all the light frequencies in heterodyne for visibility, enough of that same stuff would leak through to make strong medicine on these visiplates—for I knew that that bar weighed a hundred tons and would liberate energy enough to volatilize our Earth and blow the by-products clear to Arcturus. How're you coming, Dunark? See anything yet?"

"Coming along O. K. now, I guess—but I thought for a few minutes I'd been bloody well jobbed."

"I'll do better next time. I'll cut out the visible spectrum before the flash, and convert and reconvert the infra-red. That'll let us see what happens, without the direct effect of the glare—won't burn our eyes out. What's my force number on the next nearest one, Mart?"

"Twenty-nine."

Seaton fastened a detector ray upon stop twenty-nine of the tracer-ray panel and followed its beam of force out to the torpedo hastening upon its way toward the next doomed cruiser. Flashing ahead in its line as he had done before, he located the vessel and clamped the electrodes of force upon the prodigious driving bar. Again, as Dunark drove home the detonating switch, there was a frightful explosion and a wild glare of frenzied incandescence far out in that desolate region of interstellar space; but this time the eyes behind the visiplates were not torn by the high frequencies, everything that happened was plainly visible. One instant, there was an immense space-cruiser boring on through the void upon its horrid mission, with its full complement of the hellish Fenachrone performing their routine tasks. The next instant there was a flash of light extending for thousands upon untold thousands of miles in every direction. That flare of light vanished as rapidly as it had appeared—instantaneously—and throughout the entire neighborhood of the place where the Fenachrone cruiser had been, there was nothing. Not a plate nor a girder, not a fragment, not the most minute particle nor droplet of disrupted metal nor of condensed vapor. So terrific, so incredibly and incomprehensibly vast were the forces liberated by that mass of copper in its instantaneous decomposition, that every atom of substance in that great vessel had gone with the power-bar—had been resolved into radiations which would at some distant time and in some far-off solitude unite with other radiations, again to form matter, and thus obey Nature's immutable cyclic law.

Thus vessel after vessel was destroyed of that haughty fleet which until now had never suffered a reverse and a little green light in the galactic model winked out and flashed back in rosy pink as each menace was removed. In a few hours the space surrounding the system of the Fenachrone was clear; then progress slackened as it became harder and harder to locate each vessel as the distance between it and its torpedo increased. Time after time Seaton would stab forward with his detector screen extended to its utmost possible spread, upon the most carefully plotted prolongation of the line of the torpedo's flight, only to have the projection flash far beyond the vessel's furthest possible position without a reaction from the far-flung screen. Then he would go back to the torpedo, make a minute alteration in his line, and again flash forward, only to miss it again. Finally, after thirty fruitless attempts to bring his detector screen into contact with the nearest Fenachrone ship, he gave up the attempt, rammed his battered, reeking briar full of the rank blend that was his favorite smoke, and strode up and down the floor of the projector base—his eyes unseeing, his hands jammed deep into his pockets, his jaw thrust forward, clamped upon the stem of his pipe, emitting dense, blue clouds of strangling vapor.

"The maestro is thinking, I perceive," remarked Dorothy, sweetly, entering the projector from an airboat. "You must all be blind, I guess—you no hear the bell blow, what? I've come after you—it's time to eat!"

"'At-a-girl, Dot—never miss the eats! Thanks," and Seaton put his problem away, with perceptible effort.

"This is going to be a job, Mart," he went back to it as soon as they were seated in the airboat, flying toward "home." "I can nail them, with an increasing shift in azimuth, up to about thirty thousand light-years, but after that it gets awfully hard to get the right shift, and up around a hundred thousand it seems to be darn near impossible—gets to be pure guesswork. It can't be the controls, because they can hold a point rigidly at five hundred thousand. Of course, we've got a pretty short back-line to sight on, but the shift is more than a hundred times as great as the possible error in backsight could account for, and there's apparently nothing either regular or systematic about it that I can figure out. But.... I don't know.... Space is curved in the fourth dimension, of course.... I wonder if ... hm—m—m." He fell silent and Crane made a rapid signal to Dorothy, who was opening her mouth to say something. She shut it, feeling ridiculous, and nothing was said until they had disembarked at their destination.

"Did you solve the puzzle, Dickie?"[Pg 625]

"Don't think so—got myself in deeper than ever, I'm afraid," he answered, then went on, thinking aloud rather than addressing any one in particular:

"Space is curved in the fourth dimension, and fifth-order rays, with their velocity, may not follow the same path in that dimension that light does—in fact, they do not. If that path is to be plotted it requires the solution of five simultaneous equations, each complete and general, and each of the fifth degree, and also an exponential series with the unknown in the final exponent, before the fourth-dimensional concept can be derived ... hm—m—m. No use—we've struck something that not even Norlaminian theory can handle."

"You surprise me." Crane said. "I supposed that they had everything worked out."

"Not on fifth-order stuff—it's new, you know. It begins to look as though we'd have to stick around until every one of those torpedoes gets somewhere near its mother-ship. Hate to do it, too—it'll take six months, at least, to reach the vessels clear across the Galaxy. I'll put it up to the gang at dinner—guess they'll let me talk business a couple of minutes overtime, especially after they find out what I've got to say."

He explained the phenomenon to an interested group of white-bearded scientists as they ate. Rovol, to Seaton's surprise, was elated and enthusiastic.

"Wonderful, my boy!" he breathed. "Marvelous! A perfect subject for years after year of deepest study and the most profound thought. Perfect!"

"But what can we do about it?" asked Seaton, exasperated. "We don't want to hang around here twiddling our thumbs for a year waiting for those torpedoes to get to wherever they're going!"

"We can do nothing but wait and study. That problem is one of splendid difficulty, as you yourself realize. Its solution may well be a matter of lifetimes instead of years. But what is a year, more or less? You can destroy the Fenachrone eventually, so be content."

"But content is just exactly what I'm not!" declared Seaton, emphatically. "I want to do it, and do it now!"

"Perhaps I might volunteer a suggestion," said Caslor, diffidently; and as both Rovol and Seaton looked at him in surprise he went on: "Do not misunderstand me. I do not mean concerning the mathematical problem in discussion, about which I am entirely ignorant. But has it occurred to you that those torpedoes are not intelligent entities, acting upon their own volition and steering themselves as a result of their own ordered mental processes? No, they are mechanisms, in my own province, and I venture to say with the utmost confidence that they are guided to their destinations by streamers of force of some nature, emanating from the vessels upon whose tracks they are."

"'Nobody Holme' is right!" exclaimed Seaton, tapping his temple with an admonitory forefinger. "'Sright, ace—I thought maybe I'd quit using my head for nothing but a hatrack now, but I guess that's all it's good for, yet. Thanks a lot for the idea—that gives me something I can get my teeth into, and now that Rovol's got a problem to work on for the next century or so, everybody's happy."

"How does that help matters?" asked Crane in wonder. "Of course it is not surprising that no lines of force were visible, but I thought that your detectors screens would have found them if any such guiding beams had been present."

"The ordinary bands, if of sufficient power, yes. But there are many possible tracer rays not reactive to a screen such as I was using. It was very light and weak, designed for terrific velocity and for instantaneous automatic arrest when in contact with the enormous forces of a power bar. It wouldn't react at all to the minute energy of the kind of beams they'd be most likely to use for that work. Caslor's certainly right. They're steering their torpedoes with tracer rays of almost infinitesimal power, amplified in the torpedoes themselves—that's the way I'd do it myself. It may take a little while to rig up the apparatus, but we'll get it—and then we'll run those birds ragged—so fast that their ankles'll catch fire—and won't need the fourth-dimensional correction after all."

When the bell announced the beginning of the following period of labor, Seaton and his co-workers were in the Area of Experiment waiting, and the work was soon under way.

"How are you going about this, Dick?" asked Crane.

"Going to examine the nose of one of those torpedoes first, and see what it actually works on. Then build me a tracer detector that'll pick it up at high velocity. Beats the band, doesn't it, that neither Rovol nor I, who should have thought of it first, ever did see anything as plain as that? That those things are following a ray?"

"That is easily explained, and is no more than natural. Both of you were not only devoting all your thoughts to the curvature of space, but were also too close to the problem—like the man in the woods, who cannot see the forest because of

Comments (0)