The Cloud Dream of the Nine, Kim Man-Choong [bearly read books txt] 📗

- Author: Kim Man-Choong

- Performer: -

Book online «The Cloud Dream of the Nine, Kim Man-Choong [bearly read books txt] 📗». Author Kim Man-Choong

“I, So-yoo, in my boyhood was a poor scholar, but I have been blessed with enduring favours from his Majesty, and elevated to the highest rank. The members of my household have lived together in sweetness and accord till this time of old age. If it had not been for the affinity of a former existence, how could this have been? By reason of this mysterious bond it has all come to pass. When the term fixed for this mortal life is completed, we must part; [p293] and when once death has swept us away, even this lofty tower shall fall and the fair lake beneath us shall be dried up. This palace hall, where to-day is music and dancing, will be overgrown with grass and the mists will cover it. Children who gather wood or feed their cattle on the hillside will sing their songs and tell our mournful story, saying: ‘This is where Master Yang made merry with his wives and family. All his honours and delights, all the pretty faces of his ladies, are gone for ever.’

“The boy who gathers wood and the lad who cares for the cattle will look upon this place of ours just as I look upon the palace and tomb of the kings that have gone before us. When I think of it, a man’s life is only the span of a moment after all.

“There are three religions on earth, Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. Among the three, Buddhism is the most spiritual; Confucianism deals with terrestrial matters and has to do with the duties of man to man. It helps to pass on names to posterity. Taoism is related to the misty and unknown, and though it has many followers there is no proof of its verity.

“Since I gave up office I have dreamed of meditation before the Buddha. This is proof of my affinity with the God. Just as Chang Cha-pang [46] followed Chok Song-ja, the fairy, I, too, must say farewell to my home and go to the distant shore, there to seek the Merciful Buddha, ascend the Sacred Hall, and bow low before his image. The Way that has no birth and no death beckons to me and puts off all the sorrows of life. To you with whom I have spent so many happy days I must say a long farewell, and so my sorrow [p294] and loss is expressed by the sad notes of the green stone flute.”

The ladies in their former existence had been the eight fairies who lived on Nam-ak Mountain. Now they had fulfilled their human affinity, and hearing the Master’s word they were moved by it and said each to the other: “In the midst of all his affluence the Master’s speech is evidently at the command of God, We eight sisters who have lived our life in these inner quarters and have bowed night and morning before the Buddha shall await the departure of our lord. When he goes he will assuredly meet the Enlightened One and the righteous friends who have gone before him and will hear the words of life. Our humble wish is that after he has attained he may be pleased to teach us the way.”

The Master, greatly delighted, said: “Since your hearts are one with mine in this you need have no fear. I start to-morrow.”

The ladies all said: “We shall each raise the glass that wishes you great peace on the eternal way.”

Just at the moment when they had given orders to the serving maids to bring the glasses, the fall of a staff was heard on the stone pavement beyond the open balcony. They exclaimed: “Who has come, I wonder?”

Immediately an old priest appeared before them with eyebrows an ell long and eyes like the waves of the blue sea. His appearance and his behaviour were mysterious and wonderful. He ascended the tower, sat down before the Master, and said: “A dweller from the hills seeks audience with your Excellency.”

Already the Master knew that he was no common [p295] man, so he arose quickly and made a respectful obeisance as he replied: “Whence comes the honoured teacher?”

The old priest made answer: “Do you not know an old friend? I have heard before that you had a gift for forgetfulness, and now I find that it is true.”

The Master looked carefully and then he thought he recognised the face, but he was not sure. Suddenly he recollected, and turning to the ladies said: “When I went into Tibet against the rebels, in my dream after I had shared the feast of the Dragon King and was on my way home, I went for a little up the Nam-ak Hills and saw an aged priest sitting in the seat of the Master reciting with his disciples the sacred sutras of the Buddha. The priest whom I saw there is the same who greets me now.”

The priest clapped his hands, laughed and said: “You are right, right. You remember, however, seeing me in your dream only; the ten years that we spent together you have forgotten all about. Who would say that the Master Yang was an enlightened man?”

Yang, not knowing what he meant, replied: “When I was sixteen I was still with my parents. I then passed my examinations and from that time entered office, and did not again leave the capital till I went south as envoy. My next journey was to put down the Tibetans. There is no place that my feet have travelled over that I do not recall. When did I spend ten years with you, sir? “

The priest looked sad and said: “Your Excellency has not yet awakened from your dark dream.”

“Have you, great teacher, any means of awakening me?” asked Yang. [p296]

“That is not difficult,” said the priest. He raised his stone staff and struck the railing, when suddenly a white cloud arose all about them that came forth from the recesses of the hills till it enclosed the tower and made all dark and indistinct so that no one could see.

The Master, bewildered as in a dream, called loudly: “Will the Teacher not teach me the true way, instead of applying to me the terrors of magic?” He did not finish what he was about to say, for suddenly the clouds moved off and everybody had disappeared, including the priest and the eight ladies. He was greatly alarmed and mystified, and looked with wonder to find the tower with its ornamented curtains, but it also had passed from view. He turned his eyes upon himself to find his body, and there he was sitting cross-legged on a little round mat in a silent temple. There was an incense brazier before him from which the fires had died out. The moon was descending towards the west. He felt his head and it had just been shaved, with only the prickly roots noticeable. A string of a hundred and eight beads was round his neck, and there he was a poor insignificant priest with all the glory of General Yang departed from him. His mind and soul were hopelessly confused and his heart beat with trepidation. He suddenly awakened and said: “I am Song-jin, a priest of Yon-wha Monastery.”

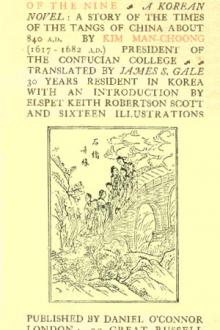

[IMG: Yang Looks away from the World: Back to Religion]

As he thought over the past he remembered how he had been reprimanded and what had followed. He recalled his flight to Hades and how he had transmigrated into human life; how he had become a clansman of the Yang family; his passing the [p297] examination and becoming a high Hallim; his promotion to the rank of General, and later to be the head of the entire official service; how he had memorialised the Emperor to resign his office; his retirement with the two Princesses and the six ladies how he had enjoyed music and dancing and the notes of the harp and lute; how he had drunk wine and played at go, and had lived his days in pleasure. Now it was all as a passing dream.

Then he said: “The Teacher indeed, knowing my great sin, sent me forth to dream this dream of life so that I might learn the fleeting character and instability of all earthly things and the vain loves of human kind.”

So he hastened to the stream of water rushing by and washed his face, put on his priest’s cassock and hat and went to take his place among the disciples before the Teacher. When they were arranged in order the Teacher called with a loud voice and said “Song-jin, how did you find the joys of mortal life?”

Song-jin bowed, shed tears, and said: “I have at last come to realise what life means. My life has been very impure and my sins I can lay at no one’s door but my own. I have loved in a lost and fallen world, where for endless kalpas I should have suffered sorrow and misery had not the honoured Teacher by a dream of the night awakened my soul to see. In the ages to come I can never, never sufficiently thank Thee for what Thou hast done for me.”

The Teacher said: “You have gone abroad on the wings of worldly delight and have seen and known for yourself. What part have I had in it, pray? You say that you have dreamed a dream of mortal life [p298] upon the wheel and that now you think the two to be different, the world and the dream itself; but that is not so. If you think it so it will show that you are not yet awakened from your sleep. Master Chang became a butterfly, and the butterfly became Master Chang. Was Chang’s becoming a butterfly a dream, or was the butterfly’s becoming Chang a dream? You, Song-jin, now think yourself reality, and your past life a dream only; you do not reckon yourself one and the same as the dream. Which shall I label the dream, you Song-jin, or you So-yoo?”

Song-jin replied: “I am a darkened soul and so cannot distinguish which is the dream and which is the actual reality. Please, Teacher, open to me the truth and let me know.”

The Teacher said: “I shall explain to you the Diamond Sutra to awaken your soul, but there are other and new disciples whom I am shortly expecting. I await their coming.”

Before he had ended speaking the gatekeeper came in to say: “The eight fairies of Lady Wee who called yesterday have again arrived before the gate and desire to see the Great Teacher.”

They were invited in, and as they entered they joined hands and bowed, saying: “We maids, though we wait upon Lady Wee, are untaught and unlearned and have never known how to repress the lawless workings of

Comments (0)