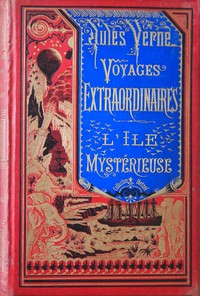

The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [classic novels .txt] 📗

- Author: Jules Verne

Book online «The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [classic novels .txt] 📗». Author Jules Verne

“Unless,” suggested Spilett, “it had been written by a companion of this man who has since died.”

“That is impossible, Spilett.”

“Why so?”

“Because, then, the paper would have mentioned two persons instead of one.”

Herbert briefly related the incident of the sea striking the sloop, and insisted that the prisoner must then have had a glimmer of his sailor instinct.

“You are perfectly right, Herbert,” said the engineer, “to attach great importance to this fact. This poor man will not be incurable; despair has made him what he is. But here he will find his kindred, and if he still has any reason, we will save it.”

Then, to Smith’s great pity and Neb’s wonderment, the man was brought up from the cabin of the sloop, and as soon as he was on land, he manifested a desire to escape. But Smith, approaching him, laid his hand authoritatively upon his shoulder and looked at him with infinite tenderness. Thereupon the poor wretch, submitting to a sort of instantaneous power, became quiet, his eyes fell, his head dropped forward, and he made no further resistance.

“Poor shipwrecked sailor,” murmured the reporter.

Smith regarded him attentively. To judge from his appearance, this miserable creature had little of the human left in him; but Smith caught in his glance, as the reporter had done, an almost imperceptible gleam of intelligence.

It was decided that the Unknown, as his new companions called him, should stay in one of the rooms of Granite House, from which he could not escape. He made no resistance to being conducted there, and with good care they might, perhaps, hope that some day he would prove a companion to them.

Neb hastened to prepare breakfast, for the voyagers were very hungry, and during the meal Smith made them relate in detail every incident of the cruise. He agreed with them in thinking that the name of the Britannia gave them reason to believe that the Unknown was either English or American; and, moreover, under all the growth of hair covering the man’s face, the engineer thought he recognized the features characteristic of an Anglo-Saxon.

“But, by the way, Herbert,” said the reporter, “you have never told us how you met this savage, and we know nothing, except that he would have strangled you, had we not arrived so opportunely.”

“Indeed, I am not sure that I can tell just what happened,” replied Herbert. “I was, I think, gathering seeds, when I heard a tremendous noise in a high tree near by. I had hardly time to turn, when this unhappy creature, who had, doubtless, been hidden crouching in the tree, threw himself upon me; and, unless Mr. Spilett and Pencroff—”

“You were in great danger, indeed, my boy,” said Smith; “but perhaps, if this had not happened, this poor being would have escaped your search, and we would have been without another companion.”

“You expect, then, to make him a man again?” asked the reporter.

“Yes,” replied Smith.

Breakfast ended, all returned to the shore and began unloading the sloop; and the engineer examined the arms and tools, but found nothing to establish the identity of the Unknown.

The pigs were taken to the stables, to which they would soon become accustomed. The two barrels of powder and shot and the caps were a great acquisition, and it was determined to make a small powder magazine in the upper cavern of Granite House, where there would be no danger of an explosion. Meantime, since the pyroxyline answered very well, there was no present need to use this powder.

When the sloop was unloaded Pencroff said:—

“I think, Mr. Smith, that it would be better to put the Good Luck in a safe place.”

“Is it not safe enough at the mouth of the Mercy?”

“No, sir,” replied the sailor. “Most of the time she is aground on the sand, which strains her.”

“Could not she be moored out in the stream?”

“She could, but the place is unsheltered, and in an easterly wind I am afraid she would suffer from the seas.”

“Very well; where do you want to put her?”

“In Balloon Harbor,” replied the sailor. “It seems to me that that little inlet, hidden by the rocks, is just the place for her.”

“Isn’t it too far off?”

“No, it is only three miles from Granite House, and we have a good straight road there.”

“Have your way, Pencroff,” replied the engineer. “Nevertheless, I should prefer to have the sloop under our sight. We must, when we have time, make a small harbor.”

“Capital!” cried Pencroff. “A harbor with a light house, a breakwater, and a dry dock! Oh, indeed, sir, everything will be easy enough with you!”

“Always provided, my good man, that you assist me, as you do three fourths of the work.”

Herbert and the sailor went aboard the Good Luck, and set sail, and in a couple of hours the sloop rode quietly at anchor in the tranquil water of Balloon Harbor.

During the first few days that the Unknown was at Granite House, had he given any indication of a change in his savage nature? Did not a brighter light illumine the depths of his intelligence? Was not, in short, his reason returning to him? Undoubtedly, yes; and Smith and Spilett questioned whether this reason had ever entirely forsaken him.

At first this man, accustomed to the air and liberty which he had had in Tabor Island, was seized with fits of passion, and there was danger of his throwing himself out of one of the windows of Granite House. But little by little he grew more quiet, and he was allowed to move about without restraint.

Already forgetting his carnivorous instincts, he accepted a less bestial nourishment, and cooked food did not produce in him the sentiment of disgust which he had shown on board the Good Luck.

Smith had taken advantage of a time when the man was asleep to cut the hair and beard which had grown like a mane about his face, and had given him such a savage aspect. He had also been clothed more decently, and the result was that the Unknown appeared more like a human being, and it seemed as if the expression of his eyes was softened. Certainly, sometimes, when intelligence was visible, the expression of this man had a sort of beauty.

Every day, Smith made a point of passing some hours in his company. He worked beside him, and occupied himself in various ways to attract his attention. It would suffice, if a single ray of light illuminated his reason, if a single remembrance crossed his mind. Neither did the engineer neglect to speak in a loud voice, so as to penetrate by both sound and sight to the depths of this torpid intelligence. Sometimes one or another of the party joined the engineer, and they usually talked of such matters pertaining to the sea as would be likely to interest the man. At times the Unknown gave a sort of vague attention to what was said, and soon the colonists began to think that he partly understood them. Again his expression would be dolorous, proving that he suffered inwardly. Nevertheless, he did not speak, although they thought, at times, from his actions, that words were about to pass his lips.

The poor creature was very calm and sad. But was not the calmness only on the surface, and the sadness the result of his confinement? They could not yet say. Seeing only certain objects and in a limited space, always with the colonists, to whom he had become accustomed, having no desire to satisfy, better clothed and better fed, it was natural that his physical nature should soften little by little; but was he imbued with the new life, or, to use an expression justly applicable to the case, was he only tamed, as an animal in the presence of its master? This was the important question Smith was anxious to determine, and meantime he did not wish to be too abrupt with his patient. For to him, the unknown was but a sick person. Would he ever be a convalescent?

Therefore, the engineer watched him unceasingly. How he laid in wait for his reason, so to speak, that he might lay hold of it.

The colonists followed with strong interest all the phases of this cure undertaken by Smith. All aided him in it, and all, save perhaps the incredulous Pencroff, came to share in his belief and hope.

The submission of the Unknown was entire, and it seemed as if he showed for the engineer, whose influence over him was apparent, a sort of attachment, and Smith resolved now to test it by transporting him to another scene, to that ocean which he had been accustomed to look upon, to the forest border, which would recall those woods where he had lived such a life!”

“But,” said Spilett, “can we hope that once at liberty, he will not escape?”

“We must make the experiment,” replied the engineer.

“All right,” said Pencroff. “You will see, when this fellow snuffs the fresh air and sees the coast clear, if he don’t make his legs spin!”

“I don’t think it,” replied the engineer.

“We will try, any how,” said Spilett.

It was the 30th of October, and the Unknown had been a prisoner for nine days. It was a beautiful, warm, sunshiny day. Smith and Pencroff went to the room of the Unknown, whom they found at the window gazing out at the sky.

“Come, my friend,” said the engineer to him.

The Unknown rose immediately. His eye was fixed on Smith, whom he followed; and the sailor, little confident in the results of the experiment, walked with him.

Having reached the door, they made him get into the elevator, at the foot of which the rest of the party were waiting. The basket descended, and in a few seconds all were standing together on the shore.

The colonists moved off a little distance from the Unknown, so as to leave him quite at liberty. He made some steps forward towards the sea, and his face lit up with pleasure, but he made no effort to escape. He looked curiously at the little waves, which, broken by the islet, died away on the shore.

“It is not, indeed, the ocean,” remarked Spilett, “and it is possible that this does not give him the idea of escaping.”

“Yes,” replied Smith, “we must take him to the plateau on the edge of the forest. There the experiment will be more conclusive.”

“There he cannot get away, since the bridges are all raised,” said Neb.

“Oh, he is not the man to be troubled by such a brook as Glycerine Creek; he could leap it at a bound,” returned Pencroff.

“We will see presently,” said Smith, who kept his eye fixed on his patient.

And thereupon all proceeded towards Prospect Plateau. Having reached the place they encountered the outskirts of the forest, with its leaves trembling in the wind, The Unknown seemed to drink in with eagerness the perfume in the air, and a long sigh escaped from his breast.

The colonists stood some paces back, ready to seize him if he attempted to escape.

The poor creature was upon the point of plunging in the creek that separated him from the forest; he placed himself ready to spring—then all at once he turned about, dropping his arms beside him, and tears coursed down his cheeks.

“Ah!” cried Smith, “you will be a man again, since you weep!”

CHAPTER XXXVIIIA MYSTERY TO BE SOLVED—THE FIRST WORDS OF THE UNKNOWN—TWELVE YEARS ON THE ISLAND—CONFESSIONS—DISAPPEARANCE—SMITH’S CONFIDENCE —BUILDING A WIND-MILL—THE FIRST BREAD—AN ACT OF DEVOTION—HONEST HANDS.

Yes, the poor creature had wept. Some remembrance had flashed across his spirit, and, as Smith had said, he would be made a man through his tears.

The colonists left him for some time, withdrawing themselves, so that he could feel perfectly at liberty; but he showed no inclination to avail himself of this freedom, and Smith soon decided to take him back to Granite House.

Two days after this occurrence, the Unknown showed a disposition to enter little by little into the common life. It was evident that he heard, that he understood, but it was equally evident that he manifested a strange disinclination to speak to them. Pencroff, listening at his room, heard these words escape him:—

“No! here! I! never!”

The sailor reported this to his companions, and Smith said:—

“There must be some sad mystery here.”

The Unknown had begun to do some little chores, and to work in the garden. When he rested, which was frequent, he seemed entirely self-absorbed; but, on the advice of the engineer, the others respected the silence, which he seemed desirous of keeping. If one of the colonists approached him he recoiled, sobbing as if overcome. Could it be by remorse? or, was it, as Spilett once suggested:—

“If he does not speak I believe it is because he has

Comments (0)