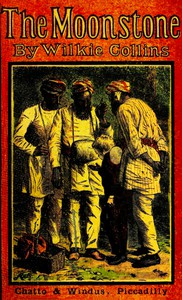

The Moonstone, Wilkie Collins [howl and other poems TXT] 📗

- Author: Wilkie Collins

Book online «The Moonstone, Wilkie Collins [howl and other poems TXT] 📗». Author Wilkie Collins

It is reported here, that you and Miss Verinder are to be married next month. Please to accept my best congratulations.

The pages of my poor friend’s Journal are waiting for you at my house—sealed up, with your name on the wrapper. I was afraid to trust them to the post.

My best respects and good wishes attend Miss Verinder. I remain, dear Mr. Franklin Blake, truly yours,

THOMAS CANDY.

EIGHTH NARRATIVE.Contributed by Gabriel Betteredge.

I am the person (as you remember no doubt) who led the way in these pages, and opened the story. I am also the person who is left behind, as it were, to close the story up.

Let nobody suppose that I have any last words to say here concerning the Indian Diamond. I hold that unlucky jewel in abhorrence—and I refer you to other authority than mine, for such news of the Moonstone as you may, at the present time, be expected to receive. My purpose, in this place, is to state a fact in the history of the family, which has been passed over by everybody, and which I won’t allow to be disrespectfully smothered up in that way. The fact to which I allude is—the marriage of Miss Rachel and Mr. Franklin Blake. This interesting event took place at our house in Yorkshire, on Tuesday, October ninth, eighteen hundred and forty-nine. I had a new suit of clothes on the occasion. And the married couple went to spend the honeymoon in Scotland.

Family festivals having been rare enough at our house, since my poor mistress’s death, I own—on this occasion of the wedding—to having (towards the latter part of the day) taken a drop too much on the strength of it.

If you have ever done the same sort of thing yourself you will understand and feel for me. If you have not, you will very likely say, “Disgusting old man! why does he tell us this?” The reason why is now to come.

Having, then, taken my drop (bless you! you have got your favourite vice, too; only your vice isn’t mine, and mine isn’t yours), I next applied the one infallible remedy—that remedy being, as you know, Robinson Crusoe. Where I opened that unrivalled book, I can’t say. Where the lines of print at last left off running into each other, I know, however, perfectly well. It was at page three hundred and eighteen—a domestic bit concerning Robinson Crusoe’s marriage, as follows:

“With those Thoughts, I considered my new Engagement, that I had a Wife”—(Observe! so had Mr. Franklin!)—“one Child born”—(Observe again! that might yet be Mr. Franklin’s case, too!)—“and my Wife then”—What Robinson Crusoe’s wife did, or did not do, “then,” I felt no desire to discover. I scored the bit about the Child with my pencil, and put a morsel of paper for a mark to keep the place; “Lie you there,” I said, “till the marriage of Mr. Franklin and Miss Rachel is some months older—and then we’ll see!”

The months passed (more than I had bargained for), and no occasion presented itself for disturbing that mark in the book. It was not till this present month of November, eighteen hundred and fifty, that Mr. Franklin came into my room, in high good spirits, and said, “Betteredge! I have got some news for you! Something is going to happen in the house, before we are many months older.”

“Does it concern the family, sir?” I asked.

“It decidedly concerns the family,” says Mr. Franklin.

“Has your good lady anything to do with it, if you please, sir?”

“She has a great deal to do with it,” says Mr. Franklin, beginning to look a little surprised.

“You needn’t say a word more, sir,” I answered. “God bless you both! I’m heartily glad to hear it.”

Mr. Franklin stared like a person thunderstruck. “May I venture to inquire where you got your information?” he asked. “I only got mine (imparted in the strictest secrecy) five minutes since.”

Here was an opportunity of producing Robinson Crusoe! Here was a chance of reading that domestic bit about the child which I had marked on the day of Mr. Franklin’s marriage! I read those miraculous words with an emphasis which did them justice, and then I looked him severely in the face. “Now, sir, do you believe in Robinson Crusoe?” I asked, with a solemnity, suitable to the occasion.

“Betteredge!” says Mr. Franklin, with equal solemnity, “I’m convinced at last.” He shook hands with me—and I felt that I had converted him.

With the relation of this extraordinary circumstance, my reappearance in these pages comes to an end. Let nobody laugh at the unique anecdote here related. You are welcome to be as merry as you please over everything else I have written. But when I write of Robinson Crusoe, by the Lord it’s serious—and I request you to take it accordingly!

When this is said, all is said. Ladies and gentlemen, I make my bow, and shut up the story.

EPILOGUE. THE FINDING OF THE DIAMOND. I THE STATEMENT OF SERGEANT CUFF’S MAN. (1849.)On the twenty-seventh of June last, I received instructions from Sergeant Cuff to follow three men; suspected of murder, and described as Indians. They had been seen on the Tower Wharf that morning, embarking on board the steamer bound for Rotterdam.

I left London by a steamer belonging to another company, which sailed on the morning of Thursday the twenty-eighth. Arriving at Rotterdam, I succeeded in finding the commander of the Wednesday’s steamer. He informed me that the Indians had certainly been passengers on board his vessel—but as far as Gravesend only. Off that place, one of the three had inquired at what time they would reach Calais. On being informed that the steamer was bound to Rotterdam, the spokesman of the party expressed the greatest surprise and distress at the mistake which he and his two friends had made. They were all willing (he said) to sacrifice their passage money, if the commander of the steamer would only put them ashore. Commiserating their position, as foreigners in a strange land, and knowing no reason for detaining them, the commander signalled for a shore boat, and the three men left the vessel.

This proceeding of the Indians having been plainly resolved on beforehand, as a means of preventing their being traced, I lost no time in returning to England. I left the steamer at Gravesend, and discovered that the Indians had gone from that place to London. Thence, I again traced them as having left for Plymouth. Inquiries made at Plymouth proved that they had sailed, forty-eight hours previously, in the Bewley Castle, East Indiaman, bound direct to Bombay.

On receiving this intelligence, Sergeant Cuff caused the authorities at Bombay to be communicated with, overland—so that the vessel might be boarded by the police immediately on her entering the port. This step having been taken, my connection with the matter came to an end. I have heard nothing more of it since that time.

II THE STATEMENT OF THE CAPTAIN. (1849.)I am requested by Sergeant Cuff to set in writing certain facts, concerning three men (believed to be Hindoos) who were passengers, last summer, in the ship Bewley Castle, bound for Bombay direct, under my command.

The Hindoos joined us at Plymouth. On the passage out I heard no complaint of their conduct. They were berthed in the forward part of the vessel. I had but few occasions myself of personally noticing them.

In the latter part of the voyage, we had the misfortune to be becalmed for three days and nights, off the coast of India. I have not got the ship’s journal to refer to, and I cannot now call to mind the latitude and longitude. As to our position, therefore, I am only able to state generally that the currents drifted us in towards the land, and that when the wind found us again, we reached our port in twenty-four hours afterwards.

The discipline of a ship (as all seafaring persons know) becomes relaxed in a long calm. The discipline of my ship became relaxed. Certain gentlemen among the passengers got some of the smaller boats lowered, and amused themselves by rowing about, and swimming, when the sun at evening time was cool enough to let them divert themselves in that way. The boats when done with ought to have been slung up again in their places. Instead of this they were left moored to the ship’s side. What with the heat, and what with the vexation of the weather, neither officers nor men seemed to be in heart for their duty while the calm lasted.

On the third night, nothing unusual was heard or seen by the watch on deck. When the morning came, the smallest of the boats was missing—and the three Hindoos were next reported to be missing, too.

If these men had stolen the boat shortly after dark (which I have no doubt they did), we were near enough to the land to make it vain to send in pursuit of them, when the discovery was made in the morning. I have no doubt they got ashore, in that calm weather (making all due allowance for fatigue and clumsy rowing), before day-break.

On reaching our port, I there learnt, for the first time, the reason these passengers had for seizing their opportunity of escaping from the ship. I could only make the same statement to the authorities which I have made here. They considered me to blame for allowing the discipline of the vessel to be relaxed. I have expressed my regret on this score to them, and to my owners.

Since that time, nothing has been heard to my knowledge of the three Hindoos. I have no more to add to what is here written.

III THE STATEMENT OF MR. MURTHWAITE. (1850.)(In a letter to Mr. Bruff.)

Have you any recollection, my dear sir, of a semi-savage person whom you met out at dinner, in London, in the autumn of ’forty-eight? Permit me to remind you that the person’s name was Murthwaite, and that you and he had a long conversation together after dinner. The talk related to an Indian Diamond, called the Moonstone, and to a conspiracy then in existence to get possession of the gem.

Since that time, I have been wandering in Central Asia. Thence I have drifted back to the scene of some of my past adventures in the north and north-west of India. About a fortnight since, I found myself in a certain district or province (but little known to Europeans) called Kattiawar.

Here an adventure befell me, in which (incredible as it may appear) you are personally interested.

In the wild regions of Kattiawar (and how wild they are, you will understand, when I tell you that even the husbandmen plough the land, armed to the teeth), the population is fanatically devoted to the old Hindoo religion—to the ancient worship of Bramah and Vishnu. The few Mahometan families, thinly scattered about the villages in the interior, are afraid to taste meat of any kind. A Mahometan even suspected of killing that sacred animal, the cow, is, as a matter of course, put to death without mercy in these parts by the pious Hindoo neighbours who surround him. To strengthen the religious enthusiasm of the people, two of the most famous shrines of Hindoo pilgrimage are contained within the boundaries of Kattiawar. One of them is Dwarka, the birthplace of the god Krishna. The other is the sacred city of Somnauth—sacked, and destroyed as long since as the eleventh century, by the Mahometan conqueror, Mahmoud of Ghizni.

Finding myself, for the second time, in these romantic regions, I resolved not to leave Kattiawar, without looking once more on the magnificent desolation of Somnauth. At the place where I planned to do this, I was (as nearly as I could calculate it) some three days distant, journeying on foot, from the sacred city.

I had not been long on the road, before I noticed that other people—by twos and threes—appeared to be travelling in the same direction as myself.

To such of these as spoke to me, I gave myself out as a Hindoo-Boodhist, from a distant province, bound on a pilgrimage. It is needless to say that my dress was of the sort to carry out this description. Add, that I know the language as well as I know my own, and that I am lean enough and brown enough to make it no easy matter to detect my European origin—and you will understand that I passed muster with the people readily: not as one of themselves, but as a stranger from a distant part of their own country.

On the second day, the number of Hindoos travelling in my direction had increased to fifties and hundreds. On the third day, the throng had swollen to thousands; all slowly converging to one point—the city

Comments (0)