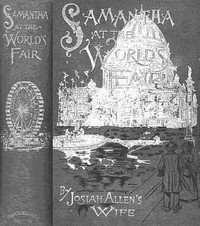

Samantha at Saratoga, Marietta Holley [most romantic novels TXT] 📗

- Author: Marietta Holley

Book online «Samantha at Saratoga, Marietta Holley [most romantic novels TXT] 📗». Author Marietta Holley

“Oh!” says he, with a relieved look. “That’s a different thing. I am willin’ to do that. I don’t know about givin’ ’em any money towards gettin’ ’em a home, but I’ll carry ’em a pound of crackers or a pound of flour, and help it along all I can.”

Josiah is a clever creeter (though close), and he never made no more objections towards havin’ it.

Wall, the next day I put on my shawl and hood (a new brown hood knit out of zephyr worsted, very nice, a present from our daughter Maggie, our son Thomas Jefferson’s wife), and sallied out to see what the neighbor’s thought about it.

The first woman I called on wuz Miss Beazley, a new neighbor who had just moved into the neighborhood. They are rich as they can be, and I expected at least to get a pound of tea out of her.

She said it wuz a worthy object, and she would love to help it along, but they had so many expenses of their own to grapple with, that she didn’t see her way clear to promise to do anything. She said the girls had got to have some new velvet suits, and some sealskin sacques this winter, and they had got to new furnish the parlors, and send their oldest boy to college, and the girls wanted to have some diamond lockets, and ought to have ’em but she didn’t know whether they could manage to get them or not, if they did, they had got to scrimp along every way they could. And then they wuz goin’ to have company from a distance, and had got to get another girl to wait on ’em. And though she wished the poor well, she felt that she could not dare to promise a cent to ’em. She wished the Smedley family well—dretful well—and hoped I would get lots of things for ’em. But she didn’t really feel as if it would be safe for her to promise’em a pound of anything, though mebby she might, by a great effort, raise a pound of flour for ’em, or meal.

Says I dryly (dry as meal ever wuz in its dryest times), “I wouldn’t give too much. Though,” says I, “A pound of flour would go a good ways if it is used right.” And I thought to myself that she had better keep it to make a paste to smooth over things.

Wall, I went from that to Miss Jacob Hess’es, and Miss Jacob Hess wouldn’t give anything because the old lady wuz disagreeable, old Grandma Smedley, and I said to Miss Jacob Hess that if the Lord didn’t send His rain and dew onto anybody only the perfectly agreeable, I guessed there would be pretty dry times. It wuz my opinion there would be considerable of a drouth.

There wuz a woman there a visitin’ Miss Hess—she wuz a stranger to me and I didn’t ask her for anything, but she spoke up of her own accord and said she would give, and give liberal, only she wuz hampered. She didn’t say why, or who, or when, but she only sez this that “she wuz hampered,” and I don’t know to this day what her hamper wuz, or who hampered her.

And then I went to Ebin Garven’ses, and Miss Ebin Garven wouldn’t help any because she said “Joe Smedley had been right down lazy, and she couldn’t call him anything else.”

“But,” says I, “Joe is dead, and why should his children starve because their pa wasn’t over and above smart when he wuz alive?” But she wouldn’t give.

Wall, Miss Whymper said she didn’t approve of the manner of giving. Her face wuz all drawed down into a curious sort of a long expression that she called religus and I called somethin’ that begins with “h-y-p-o”—and I don’t mean hypoey, either.

No, she couldn’t give, she said, because she always made a practise of not lettin’ her right hand know what her left hand give.

And I said, for I wuz kinder took aback, and didn’t think, I said to her, a glancin’ at her hands which wuz crossed in front of her, that I didn’t see how she managed it, unless she give when her right hand was asleep.

And she said she always gave secret.

And I said, “So I have always s’posed—very secret.”

I s’pose my tone was some sarcastic, for she says, “Don’t the Scripter command us to do so?”

Says I firmly, “I don’t believe the Scripter means to have us stand round talkin’ Bible, and let the Smedleys starve,” says I. “I s’pose it means not to boast of our good deeds.”

Says she, “I believe in takin’ the Scripter literal, and if I can’t git my stuff there entirely unbeknown to my right hand I sha’n’t give.”

“Wall,” says I, gettin’ up and movin’ towards the door, “you must do as you’re a mind to with fear and tremblin’.”

I said it pretty impressive, for I thought I would let her see I could quote Scripter as well as she could, if I sot out.

But good land! I knew it wuz a excuse. I knew she wouldn’t give nothin’ not if her right hand had the num palsy, and you could stick a pin into it—no, she wouldn’t give, not if her right hand was cut off and throwed away.

Wall, Miss Bombus, old Dr. Bombus’es widow, wouldn’t give—and for all the world—I went right there from Miss Whymper’ses. Miss Bombus wouldn’t give because I didn’t put the names in the Jonesville Augur or Gimlet, for she said, “Let your good deeds so shine.”

“Why,” says I, “Miss Whymper wouldn’t give because she wanted to give secreter, and you won’t give because you want to give publicker, and you both quote Scripter, but it don’t seem to help the Smedleys much.”

She said that probably Miss Whymper was wrestin’ the Scripter to her own destruction.”

“Wall,” says I, “while you and Miss Whymper are a wrestin’ the Scripter, what will become of the Smedleys? It don’t seem right to let them ‘freeze to death, and starve to death, while we are a debatin’ on the ways of Providence.”

But she didn’t tell, and she wouldn’t give.

A woman wuz there a visitin’, Miss Bombus’es aunt, I think, and she spoke up and said that she fully approved of her niece Bombus’es decision. And she said, “As for herself, she never give to any subject that she hadn’t thoroughly canvassed.”

Says I, “There they all are in that little hut, you can canvass them at any time. Though,” says I, thoughtfully, “Marvilla might give you some trouble.” And she asked why.

And I told her she had the rickets so she couldn’t stand still to be canvassed, but she could probably follow her up and canvass her, if she tried hard enough. And says I, “There is old Grandma Smedley, over eighty, and five children under eight, you can canvass them easy.”

Says she, “The Bible says, ‘Search the Sperits.’”

And I was so wore out a seein’ how place after place, for three times a runnin the Bible was lifted up and held as a shield before stingy creeters, to ward off the criticism of the world and their own souls, that I says to myself—loud enough so they could hear me, mebbe, “Why is it that when anybody wants to do a mean, ungenerous act, they will try to quote a verse of Scripter to uphold ’em, jest as a wolf will pull a lock of pure white wool over his wolfish foretop, and try to look innocent and sheepish.”

I don’t care if they did hear me, I wuz on the step mostly when I thought it, pretty loud.

Wall, from Miss Bombus’es I went to Miss Petingill’s.

Miss Petingill is a awful high-headed creeter. She come to the door herself and she said, I must excuse her for answerin’ the door herself. (I never heard the door say anything and don’t believe she did, it was jest one of her ways.) But she said I must excuse her as her girl wuz busy at the time.

She never mistrusted that I knew her hired girl had left, and she wuz doin’ her work herself. She had ketched off her apron I knew, as she come through the hall, for I see it a layin’ behind the door, all covered with flour. And after she had took me into the parlor, and we had set down, she discovered some spots of flour on her dress, and she said she “had been pastin’ some flowers into a scrap book to pass away the time.” But I knew she had been bakin’ for she looked tired, tired to death almost, and it wuz her bakin’ day. But she would sooner have had her head took right off than to own up that she had been doin’ housework—why, they say that once when she wuz doin’ her work herself, and was ketched lookin’ awful, by a strange minister, that she passed herself off’ for a hired girl and said, “Miss Petingill wasn’t to home, and when pressed hard she said she hadn’t “the least idee where Miss Petingill wuz.”

Jest think on ’t once—and there she wuz herself. The idee!

Wall, the minute I sot down before I begun my business or anything, Miss Petingill took me to do about puttin’ in Miss Bibbins President of our Missionary Society for the Relief of Indignent Heathens.

The Bibbins’es are good, very good, but poor.

Says Miss Petingill: “It seems to me as if there might be some other woman put in, that would have had more influence on the Church.”

Says I, “Haint Miss Bibbins a good Christian sister, and a great worker?”

“Why yes, she wuz good, good in her place. But,” she said, “the Petingills hadn’t never associated with the Bibbins’es.”

And I asked her if she s’posed that would make any difference with the heathen; if the heathen would be apt to think less of Miss Bibbins because she hadn’t associated with the Petingills?

And she said, she didn’t s’pose “the heathens would ever know it; it might make some difference to ’em if they did,” she thought, “for it couldn’t be denied,” she said, “that Miss Bibbins did not move in the first circles of Jonesville.”

It had been my doin’s a puttin’ Miss Bibbins in and I took it right to home, she meant to have me, and I asked her if she thought the Lord would condemn Miss Bibbins on the last day, because she hadn’t moved in the first circles of Jonesville?

And Miss Petingill tosted her head a little, but had to own up, that she thought “He wouldn’t.”

“Wall, then,” sez I, “do you s’pose the Lord has any objections to her working for Him now?”

“Why no, I don’t know as the Lord would object.”

“Wall,” sez I, “we call this work the Lord’s work, and if He is satisfied with Miss Bibbins, we ort to be.”

But she kinder nestled round, and I see she wuzn’t satisfied, but I couldn’t stop to argue, and I tackled her then and there about the Smedleys. I asked her to give a pound, or pounds, as she felt disposed.

But she answered me firmly that she could’t give one cent to the Smedleys, she wuz principled against it.

And I asked her, “Why?”

And she said, because the old lady wuz proud and wanted a home, and she thought that pride wuz so wicked, that it ort to be put down.

Wall, Miss Huff, Miss Cephas Huff, wouldn’t give anything because one of the little Smedleys had lied to her. She wouldn’t encourage lyin’.

And I told her I didn’t believe she would be half so apt to reform him on an empty stomach, as after he wuz fed up. But she wouldn’t yield.

Wall, Miss Daggett said she would give, and give abundant, only she didn’t consider it a worthy object.

But it wuzn’t nothin’ only a excuse, for the object has never been found yet that she thought wuz a worthy one. Why, she wouldn’t give a cent towards painting the Methodist steeple, and if that haint a high and worthy object, I don’t know what is. Why, our steeple is over seventy feet from the ground. But she wouldn’t help us a mite—not a single cent.

Take such folks as them and the object never suits ’em. They won’t come right out and tell the truth that they are too stingy and mean to give away a cent, but they will always put the excuse onto the object—the object don’t suit ’em.

Why, I do believe it is the livin’ truth that if the angel Gabriel wuz the object, if he wuz in need and we wuz gittin’ up a

Comments (0)