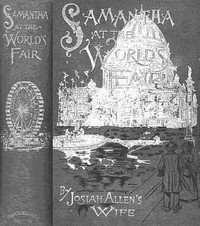

Samantha at Saratoga, Marietta Holley [most romantic novels TXT] 📗

- Author: Marietta Holley

Book online «Samantha at Saratoga, Marietta Holley [most romantic novels TXT] 📗». Author Marietta Holley

The oldest one wuz very sharp in her face and had a pair of small round eyes that seemed when they were sot onto you to sort a bore into you like two gimlets. Her nose was very sharp and defient, as if it wuz constantly sayin’ to itself, “I am a nose to be looked up to, I am a nose to be respected, and feared if necessary.” Her chin said the same thing, and her lips which wuz very thin, and her elbow, which wuz very sharp.

Her dress was a stiff sort of a shinin’ poplin, made tight acrost the chest and elboes. And her hat had some stiff feathers in it that stood up straight and sort a sharp lookin’. She had a long sharp breast-pin sort a stabbed in through the front of her stiff standin’ collar, and her knuckles sot out through her firm lisle thread gloves, her umberell wuz long and wound up hard, to that extent I have never seen before nor sense. She wuz, take it all in all, a hard sight, and skairful.

The other one wuzn’t no more like her in looks than a soft fat young cabbage head is like the sharp bean pole that it grows up by the side on, in the same garden. She wuz soft in her complexion, her lips, her cheeks, her hands, and as I mistrusted at that first minute, and found out afterwards, soft in her head too. Her dress wuz a loose-wove parmetty, full in the waist and sort a drabbly round the bottom. Her hat wuz drab-colored felt with some loose ribbon bows a hangin’ down on it, and some soft ostridge tips. She had silk mits on and her hands wuz fat and kinder moist-lookin’. Her eyes wuz very large and round, and blue, and looked sort o’ dreamy and wanderin’ and there wuz a kind of a wrapped smile on her face all the time. She had a roll of paper in her hand and I didn’t dislike her looks a mite.

Finally the oldest female opened her lips, some as a steel trap would open sudden and kinder sharp, and sez she: “I am Miss Deacon Tutt, of Tuttville, and this is my second daughter Ardelia. Cordelia is my oldest, and I have 4 younger than Ardelia.”

I bowed real polite and said, “I wuz glad to make the acquaintance of the hull 7 on ’em.” I can be very genteel when I set out, almost stylish.

“I s’pose,” says she, “I am talkin’ to Josiah Allen’s wife?”

I gin her to understand that that wuz my name and my station, and she went on, and sez she: “I have hearn on you through my husband’s 2d cousin, Cephas Tutt.”

“Cephas,” sez she, “bein’ wrote to by me on the subject of Ardelia, the same letter containin’ seven poems of hern, and on bein’ asked to point out the quickest way to make her name and fame known to the world at large, wrote back that he havin’ always dealt in butter and lard, wuzn’t up to the market price in poetry, and that you would be a good one to go to for advice. And so,” sez she a pointin’ to a bag she carried on her arm (a hard lookin’ bag made of crash with little bullets and knobs of embroidery on it), “and so we took this bag full of Ardelia’s poetry and come on the mornin’ train, Cephas’es letter havin’ reached us at nine o’clock last night. I am a woman of business.”

The bag would hold about 4 quarts and it wuz full. I looked at it and sithed.

“I see,” sez she, “that you are sorry that we didn’t bring more poetry with us. But we thought that this little batch would give you a idee of what a mind she has, what a glorious, soarin’ genus wuz in front of you, and we could bring more the next time we come.”

I sithed agin, three times, but Miss Tutt didn’t notice ’em a mite no more’n they’d been giggles or titters. She wouldn’t have took no notice of them. She wuz firm and decided doin’ her own errent, and not payin’ no attention to anything, nor anybody else.

“Ardelia, read the poem you have got under your arm to Miss Allen! The bag wuz full of her longer ones,” sez she, “but I felt that I must let you hear her poem on Spring. It is a gem. I felt it would be wrongin’ you, not to give you that treat. Read it Ardelia.”

I see Ardelia wuz used to obeyin’ her ma. She opened the sheet to once, and begun. It wuz as follows:

“ARDELIA TUTT ON SPRING.”

“Oh spring, sweet spring, thou comest in the spring;

Thou comest in the spring time of the year.

We fain would have thee come in Autumn; fling-

est thou so sad a shade, oh Spring, so dear?

“So dear the hopes thou draggest in thy rear,

So mournful, and so wan, and not so sweet;

So weird thou art, and oh, all! all! too dear

Art thou, alas! oh mournful spring; my ear—

“My ear that long did lay at gate of hope,

Prone at the gate while years glided by—

I fain would lift that ear, alas, why cope

With cruel wrong, it must lie there so heavy ’tis my eye—

“My eye, I fling o’er buried ruins long,

I flung it there, regardless of the loss;

That eye, I fain would gather in with song;

In vain! ’tis gone, I bow and own the cross.

“Dear ear, lone eye, sweet buried hopes, alas,

I give thee to the proud inexorable main;

Deep calls to deep, and it doth not reply,

But sayeth my heart, they will not be mine own again.”

Jest the minute Ardelia stopped readin’ Miss Tatt says proudly: “There! haint that a remarkable poem,?”

Sez I, calmly, “Yes it is a remarkable one.”

“Did you ever hear anything like it?” says she, triumphly.

“No,” sez I honestly, “I never did.”

“Ardelia, read the poem on Little Ardelia Cordelia; give Miss Allen the treat of hearin’ that beautiful thing.”

I sort a sithed low to myself; it wuz more of a groan than a common sithe, but Miss Tutt didn’t heed it, she kep’ right on—

“I have always brought up my children to make other folks happy, all they can, and in rehearsin’ this lovely and remarkable poem, Ardelia will be not only makin’ you perfectly happy, givin’ you a rich intellectual feast, that you can’t often have, way out here in the country, fur from Tuttville; but she will also be attendin’ to the business that brought us here. I have always fetched my children up to combine joy and business; weld ’em together like brass and steel. Ardelia, begin!”

So Ardelia commenced agin’. It wuz wrote on a big sheet of paper and a runnin’ vine wuz a runnin’ all ’round the edge of the paper, made with a pen, it was as follows:

“STANZAS ENTITLED

“SWEET LITTLE THING.

“Wrote on the death of Ardelia Cordelia, who died at the age of seven days and seven hours.”

“Sweet little thing, that erst so soon did bloom,

And didest but fade, as falls the mystic flower!

Sweet little thing, we did but erst low croon

To thee a plaintive lay, and lo! for hour and hour—

Sweet little thing.

“For hours we sang to thee of high emprise, the songs of hope

Though aged but week (and seven hours) thou laughested in thy sleep;

We cling to that in peace, though mope

The dullard knave, and biddest us go and weep—

Sweet little thing.

“Thou laughested at high emprise, and yet, in sooth,

’Twere craven to say thou couldst not rise

To scale the mounts! to soar the cliffs! if worth

Were the test, twice worthy thou, in that the merit lies—

Sweet little thing.

“Thy words that might have shook the breathless world with might;

Alas! I catchested not on any earthly ground,

That voice that might have guided nations high aright,

Congealed within thy tiny windpipe ’twas, it did not steal around—

Sweet little thing.

“Sweet little thing, so soon thy wings unfurled

A wing, a feather lone low floated up the yard;

A world might weep, a world might stand appalled,

To hear it low rehearsed by tearful female bard—

Sweet little thing.”

Jest as soon as Ardelia stopped rehearsin’ the verses, Miss Tutt sez agin to me:

“Haint that a most remarkable poem?”

And agin I sez calmly, and trutbfully, “Yes, it is a very remarkable one!”

“And now,” sez Miss Tutt, plungin’ her hand in the bag, and drawin’ out a sheet of paper, “to convince you that Ardelia has always had this divine gift of poesy—that it is not, all the effect of culture and high education—let me read to you a poem she wrote when she wuz only a mere child,” and Miss Tutt read:

“LINES ON A CAT

“WRITTEN BY ARDELIA TUTT,

“At the age of fourteen years, two months and eight days.

“Oh Cat! Sweet Tabby cat of mine;

6 months of age has passed o’er thee,

And I would not resign, resign

The pleasure that I find in you.

Dear old cat!”

“Don’t you think,” sez Miss Tutt, “that this poem shows a fund of passion, a reserve power of passion and constancy, remarkable in one so young?”

“Yes,” sez I reasonably, “no doubt she liked the cat. And,” sez I, wantin’ to say somethin’ pleasant and agreeable to her, “no doubt it was a likely cat.”

“Oh the cat itself is of miner importance,” sez Miss Tutt. “We will fling the cat to the winds. It’s of my daughter I would speak. I simply handled the cat to show the rare precocious intellect. Oh! how it gushed out in the last line in the unconquerable burst of repressed passion—’Dear old cat!’ Shakespeare might have wrote that line, do you not think so?”

“No doubt he might,” sez I, calmly, “but he didn’t.”

I see she looked mad and I hastened to say: “He wuzn’t aquainted with the cat.”

She looked kinder mollyfied and continued:

“Ardelia dashes off things with a speed that would astonish a mere common writer. Why she dashed off thirty-nine verses once while she wuz waitin’ for the dish water to bile, and sent ’em right off to the printer, without glancin’ at ’em agin.’

“I dare say so,” sez I, “I should judge so by the sound on ’em.”

“Out of envy and jealousy, the rankest envy, and the shearest jealousy, them verses wuz sent back with the infamous request that she should use ’em for curl papers. But she sot right down and wrote forty-eight verses on a ‘Cruel Request,’ wrote ’em inside of eighteen minutes. She throws off things, Ardelia does, in half an hour, that it would take other poets, weeks and weeks to write.”

“I persume so,” sez I, “I dare persume to say, they never could write ’em.”

“And now,” sez Miss Tutt, “the question is, will you put Ardelia on the back of that horse that poets ride to glory on? Will you lift her onto the back of that horse, and do it at once? I require nothin’ hard of you,” sez she, a borin’ me through and through with her eyes. “It must be a joy to you, Josiah Allen’s wife, a rare joy, to be the means of bringin’ this rare genius before the public. I ask nothin’ hard of you, I only ask that you demand, demand is the right word, not ask; that would be grovelin’ trucklin’ folly, but demand that the public that has long ignored my daugther Ardelia’s claim to a seat amongst the immortal poets, demand them, compel them to pause, to listen, and then seat her there, up, up on the highest, most perpendiciler pinnacle of fame’s pillow. Will you do this?”

I sat in deep dejection and my rockin’ chair, and knew not what to say—and Miss Tutt went on:

“We demand more than fame, deathless, immortal fame for ’em. We want money, wealth for ’em, and want it at once! We want it for extra household expenses, luxuries, clothing, jewelry, charity, etc. If we enrich the world with this rare genius, the world must enrich us with its richest emmolients. Will you see that we have it! Will you at once do as I asked you to? Will you seat

Comments (0)