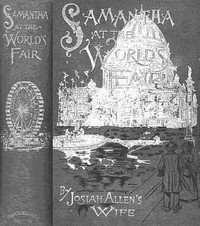

Samantha at Saratoga, Marietta Holley [most romantic novels TXT] 📗

- Author: Marietta Holley

Book online «Samantha at Saratoga, Marietta Holley [most romantic novels TXT] 📗». Author Marietta Holley

This is a sort of a curius world, and it makes me feel curius a good deal of the time as we go through it. But we have to make allowances for it, for the old world is on a tramp, too. It can’t seem to stop a minute to oil up its old axeltrys—it moves on, and takes us with it. It seems to be in a hurry.

Everything seems to be in a hurry here below. And some say Heaven is a place of continual sailin’ round and goin’ up and up all the time. But while risin’ up and soarin’ is a sweet thought to me, still sometimes I love to think that Heaven is a place where I can set down, and set for some time.

I told Josiah so (waked him up, for he wuz asleep), and he said he sot more store on the golden streets, and the wavin’ palms, and the procession of angels. (And then he went to sleep agin.)

But I don’t feel so. I’d love, as I say, to jest set down for quite a spell, and set there, to be kinder settled down and to home with them whose presence makes a home anywhere. I wouldn’t give a cent to sail round unless I wuz made to know it wuz my duty to sail. Josiah wants to.

But, as I say, everybody is in a hurry. Husbands can’t hardly find time to keep up a acquaintance with their wives. Fathers don’t have no time to get up a intimate acquaintance with their children. Mothers are in such a hurry—babys are in such a hurry—that they can’t scarcely find time to be born. And I declare for’t, it seems sometimes as if folks don’t want to take time to die.

The old folks at home wait with faithful, tired old eyes for the letter that don’t come, for the busy son or daughter hasn’t time to write it—no, they are too busy a tearin’ up the running vine of affection and home love, and a runnin’ with it.

Yes, the hull nation is in a hurry to get somewhere else, to go on, it can’t wait. It is a trampin’ on over the Western slopes, a trampin’ over red men, and black men, and some white men a hurryin’ on to the West—hurryin’ on to the sea. And what then?

Is there a tide of restfulness a layin’ before it? Some cool waters of repose where it will bathe its tired forward, and its stun-bruised feet, and set there for some time?

I don’t s’pose so. I don’t s’pose it is in its nater to. I s’pose it will look off longingly onto the far off somewhere that lays over the waters—beyend the sunset.

JOSIAH ALLEN’S WIFE.

NEW YORK, June, 1887.

SAMANTHA AT SARATOGA.

The idee on’t come to me one day about sundown, or a little before sundown. I wuz a settin’ in calm peace, and a big rockin’ chair covered with a handsome copperplate, a readin’ what the Sammist sez about “Vanity, vanity, all is vanity.” The words struck deep, and as I said, it was jest that very minute that the idee struck me about goin’ to Saratoga. Why I should have had the idee at jest that minute, I can’t tell, nor Josiah can’t. We have talked about it sense.

But good land! such creeters as thoughts be never wuz, nor never will be. They will creep in, and round, and over anything, and get inside of your mind (entirely unbeknown to you) at any time. Curious, haint it?—How you may try to hedge ’em out, and shet the doors and everything. But they will creep up into your mind, climb up and draw up their ladders, and there they will be, and stalk round independent as if they owned your hull head; curious!

Well, there the idee wuz—I never knew nothin’ about it, nor how it got there. But there it wuz, lookin’ me right in the face of my soul, kinder pert and saucy, sayin’, “You’d better go to Saratoga next summer; you and Josiah.”

But I argued with it. Sez I, “What should we go to Saratoga for? None of the relations live there on my side, or on hison; why should we go?”

But still that idee kep’ a hantin me; “You’d better go to Saratoga next summer, you and Josiah.” And it whispered, “Mebby it will help Josiah’s corns.” (He is dretful troubled with corns.) And so the idee kep’ a naggin’ me, it nagged me for three days and three nights before I mentioned it to my Josiah. And when I did, he scorfed at the idee. He said, “The idee of water curing them dumb corns—“

Sez I, “Josiah Allen, stranger things have been done;” sez I, “that water is very strong. It does wonders.”

And he scorfed agin and sez, “Don’t you believe faith could cure em?”

Sez I, “If it wuz strong enough it could.”

But the thought kep a naggin’ me stiddy, and then—here is the curious part of it—the thought nagged me, and I nagged Josiah, or not exactly nagged; not a clear nag; I despise them, and always did. But I kinder kep’ it before his mind from day to day, and from hour to hour. And the idee would keep a tellin’ me things and I would keep a tellin’ ’em to my companion. The idee would keep a sayin’ to me, “It is one of the most beautiful places in our native land. The waters will help you, the inspirin’ music, and elegance and gay enjoyment you will find there, will sort a uplift you. You had better go there on a tower;” and agin it sez, “Mebby it will help Josiah’s corns.”

And old Dr. Gale a happenin’ in at about that time, I asked him about it (he doctored me when I wuz a baby, and I have helped ’em for years. Good old creetur, he don’t get along as well as he ort to. Loontown is a healthy place.) I told him about my strong desire to go to Saratoga, and I asked him plain if he thought the water would help my pardner’s corns. And he looked dreadful wise and he riz up and walked across the floor 2 and fro several times, probably 3 times to, and the same number of times fro, with his arms crossed back under the skirt of his coat and his eyebrows knit in deep thought, before he answered me. Finely he said, that modern science had not fully demonstrated yet the direct bearing of water on corn. In some cases it might and probably did stimulate ’em to greater luxuriance, and then again a great flow of water might retard their growth.

Sez I, anxiously, “Then you’d advise me to go there with him?”

“Yes,” sez he, “on the hull, I advise you to go.”

Them words I reported to Josiah, and sez I in anxious axents, “Dr. Gale advises us to go.”

And Josiah sez, “I guess I shan’t mind what that old fool sez.”

Them wuz my pardner’s words, much as I hate to tell on ’em. But from day to day I kep’ it stiddy before him, how dang’r’us it wuz to go ag’inst a doctor’s advice. And from day to day he would scorf at the plan. And I, ev’ry now and then, and mebby oftener, would get him a extra good meal, and attack him on the subject immegatly afterwards. But all in vain. And I see that when he had that immovible sotness onto him, one extra meal wouldn’t soften or molify him. No, I see plain I must make a more voyalent effort. And I made it. For three stiddy days I put before that man the best vittles that these hands could make, or this brain could plan.

And at the end of the 3d day I gently tackled him agin on the subject, and his state wuz such, bland, serene, happified, that he consented without a parlay. And so it wuz settled that the next summer we wuz to go to Saratoga. And he began to count on it and make preparation in a way that I hated to see.

Yes, from the very minute that our two minds wuz made up to go to Saratoga Josiah Allen wuz set on havin’ sunthin new and uneek in the way of dress and whiskers. I looked coldly on the idee of puttin’ a gay stripe down the legs of the new pantaloons I made for him, and broke it up, also a figured vest. I went through them two crisises and came out triumphent.

Then he went and bought a new bright pink necktie with broad long ends which he intended to have float out, down the front of his vest. And I immegatly took it for the light-colored blocks in my silk log-cabin bedquilt. Yes, I settled the matter of that pink neck-gear with a high hand and a pair of shears. And Josiah sez now that he bought it for that purpose, for the bedquilt, because he loves to see a dressy quilt,—sez he always enjoys seein’ a cabin look sort o’ gay. But good land! he didn’t. He intended and calculated to wear that neck-tie into Saratoga,—a sight for men and angels, if I hadn’t broke it up.

But in the matter of whiskers, there I was powerless. He trimmed ’em (unbeknow to me) all off the side of his face, them good honerable side whiskers of hisen, that had stood by him for years in solemnity and decency, and begun to cultivate a little patch on the end of his chin. I argued with him, and talked well on the subject, eloquent, but it wuz of no use, I might as well have argued with the wind in March.

He said, he wuz bound on goin’ into Saratoga with a fashionable whisker, come what would.

And then I sithed, and he sez,—“ You have broke up my pantaloons, my vest, and my neck-tie, you have ground me down onto plain broadcloth, but in the matter of whiskers I am firm! Yes!” sez he “on these whiskers I take my stand!”

And agin I sithed heavy, and I sez in a dretful impressive way, as I looked on ’em, “Josiah Allen, remember you are a father and a grandfather!”

And he sez firmly, “If I wuz a great-grandfather I would trim my whiskers in jest this way, that is if I wuz a goin’ to set up to be fashionable and a goin’ to Saratoga for my health.”

And I groaned kinder low to myself, and kep’ hopin’ that mebby they wouldn’t grow very fast, or that some axident would happen to ’em, that they would get afire or sunthin’. But they didn’t. And they grew from day to day luxurient in length, but thin. And his watchful care kep’ ’em from axident, and I wuz too high princepled to set fire to ’em when he wuz asleep, though sometimes, on a moonlight night, I was tempted to, sorely tempted.

But I didn’t, and they grew from day to day, till they wuz the curiusest lookin’ patch o’ whiskers that I ever see. And when we sot out for Saratoga, they wuz jest about as long as a shavin’ brush, and looked some like one. There wuz no look of a class-leader, and a perfesser about ’em, and I told him so. But he worshiped ’em, and gloried in the idee of goin’ afar to show ’em off.

But the neighbors received the news that we wuz goin’ to a waterin’ place coldly, or with ill-concealed envy.

Uncle Jonas Bently told us he shouldn’t think we would want to go round to waterin’ troughs at our age.

And I told him it wuzn’t a waterin’ trough, and if it wuz, I thought our age wuz jest as good a one as any, to go to it.

He had the impression that Saratoga wuz a immense waterin’ trough where the country all drove themselves summers to be watered. He is deef as a Hemlock post, and I yelled up at him jest as loud as I dast for fear of breakin’ open my own chest, that the water got into us, instid of our gettin’ into the water, but I didn’t make him understand, for I hearn afterwards of his sayin’ that, as

Comments (0)