All About Coffee, William H. Ukers [short story to read .txt] 📗

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Book online «All About Coffee, William H. Ukers [short story to read .txt] 📗». Author William H. Ukers

Let proudly rule as King the Great Kauhee,

For he gives joy divine to all that ask,

Together with his spouse, sweet Eau de Vie

Oh, let us 'neath his sovran pleasure bask.

Come, raise the fragrant cup and bend the knee!

II

O great Kauhee, thou democratic Lord,

Born 'neath the tropic sun and bronzed to splendour

In lands of Wealth and Wisdom, who can render

Such service to the wandering Human Horde

As thou at every proud or humble board?

Beside the honest workman's homely fender,

'Mid dainty dames and damsels sweetly tender,

In china, gold and silver, have we poured

Thy praise and sweetness, Oriental King.

Oh, how we love to hear the kettle sing

In joy at thy approach, embodying

The bitter, sweet and creamy sides of life;

Friend of the People, Enemy of Strife,

Sons of the Earth have born thee labouring.

In America, too, poets have sung in praise of coffee. The somewhat doubtful "kind that mother used to make" is celebrated in James Whitcomb Riley's classic poem:

Like His Mother Used To Make[351]

"Uncle Jake's Place," St. Jo., Mo., 1874.

"I was born in Indiany," says a stranger, lank and slim,

As us fellers in the restaurant was kindo' guyin' him,

And Uncle Jake was slidin' him another punkin pie

And a' extry cup o' coffee, with a twinkle in his eye—

"I was born in Indiany—more'n forty years ago—

And I hain't ben back in twenty—and I'm work-in' back'ards slow;

But I've et in ever' restarunt twixt here and Santy Fee,

And I want to state this coffee tastes like gittin' home, to me!"

"Pour us out another. Daddy," says the feller, warmin' up,

A-speakin' crost a saucerful, as Uncle tuk his cup—

"When I see yer sign out yander," he went on, to Uncle Jake—

"'Come in and git some coffee like yer mother used to make'—

I thought of my old mother, and the Posey county farm,

And me a little kid again, a-hangin' in her arm,

As she set the pot a-bilin', broke the eggs and poured 'em in"—

And the feller kindo' halted, with a trimble in his chin;

And Uncle Jake he fetched the feller's coffee back, and stood

As solemn, fer a minute, as a' undertaker would;

Then he sorto' turned and tiptoed to'rds the kitchen door—and next,

Here comes his old wife out with him, a-rubbin' of her specs—

And she rushes fer the stranger, and she hollers out, "It's him!—

Thank God we've met him comin'!—Don't you know yer mother, Jim?"

And the feller, as he grabbed her, says,—"You bet I hain't forgot—

But," wipin' of his eyes, says he, "yer coffee's mighty hot!"

One of the most delightful coffee poems in English is Francis Saltus' (d. 1889) sonnet on "the voluptuous berry", as found in Flasks and Flagons:

Coffee

Voluptuous berry! Where may mortals find

Nectars divine that can with thee compare,

When, having dined, we sip thy essence rare,

And feel towards wit and repartee inclined?

Thou wert of sneering, cynical Voltaire,

The only friend; thy power urged Balzac's mind

To glorious effort; surely Heaven designed

Thy devotees superior joys to share.

Whene'er I breathe thy fumes, 'mid Summer stars,

The Orient's splendent pomps my vision greet.

Damascus, with its myriad minarets, gleams!

I see thee, smoking, in immense bazaars,

Or yet, in dim seraglios, at the feet

Of blond Sultanas, pale with amorous dreams!

Arthur Gray, in Over the Black Coffee (1902) has made the following contribution to the poetry of coffee, with an unfortunate reflection on tea, which might well have been omitted:

Coffee

O, boiling, bubbling, berry, bean!

Thou consort of the kitchen queen—

Browned and ground of every feature,

The only aromatic creature,

For which we long, for which we feel,

The breath of morn, the perfumed meal.

For what is tea? It can but mean,

Merely the mildest go-between.

Insipid sobriety of thought and mind

It "cuts no figure"—we can find—

Save peaceful essays, gentle walks,

Purring cats, old ladies' talks—

But coffee! can other tales unfold.

Its history's written round and bold—

Brave buccaneers upon the "Spanish Main",

The army's march across the lenght'ning plain,

The lone prospector wandering o'er the hill,

The hunter's camp, thy fragrance all distill.

So here's a health to coffee! Coffee hot!

A morning toast! Bring on another pot.

The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal published in 1909 the following excellent stanzas by William A. Price:

An Ode to Coffee

Oh, thou most fragrant, aromatic joy, impugned, abused, and often stormed against,

And yet containing all the blissfulness that in a tiny cup could be condensed!

Give thy contemners calm, imperial scorn—

For thou wilt reign through ages yet unborn!

Some ancient Arab, so the legend tells, first found thee—may his memory be blest!

The world-wide sign of brotherhood today, the binding tie between the East and West!

Good coffee pleases in a Persian dell,

And Blackfeet Indians make it more than well.

The lonely traveler in the desert range, if thou art with him, smiles at eventide—

The sailor, as thy perfume bubbles forth, laughs at the ocean as it rages wide—

And where the camps of fighting men are found

Thy fragrance hovers o'er each battleground.

"Use, not abuse, the good things of this life"—that is a motto from the Prophet's days,

And, dealing with thee thus, we ne'er shall come to troublous times or parting of the ways.

Comfort and solace both endure with thee,

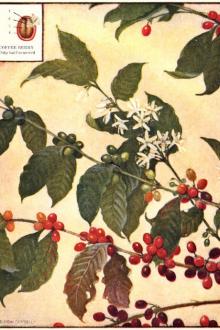

Rich, royal berry of the coffee tree!

The New York Tribune published in 1915 the following lines by Louis Untermeyer, which were subsequently included in his "—— and Other Poets."[352]

Gilbert K. Chesterton Rises to the Toast of Coffee

Strong wine it is a mocker; strong wine it is a beast.

It grips you when it starts to rise; it is the Fabled Yeast.

You should not offer ale or beer from hops that are freshly picked,

Nor even Benedictine to tempt a benedict.

For wine has a spell like the lure of hell, and the devil has mixed the brew;

And the friends of ale are a sort of pale and weary, witless crew—

And the taste of beer is a sort of a queer and undecided brown—

But, comrades, I give you coffee—drink it up, drink it down.

With a fol-de-rol-dol and a fol-de-rol-dee, etc.

Oh, cocoa's the drink for an elderly don who lives with an elderly niece;

And tea is the drink for studios and loud and violent peace—

And brandy's the drink that spoils the clothes when the bottle breaks in the trunk;

But coffee's the drink that is drunken by men who will never be drunk.

So, gentlemen, up with the festive cup, where Mocha and Java unite;

It clears the head when things are said too brilliant to be bright!

It keeps the stars from the golden bars and the lips of the tipsy town;

So, here's to strong, black coffee—drink it up, drink it down!

With a fol-de-rol-dol and a fol-de-rol-dee, etc.

The American breakfast cup is celebrated in up-to-date American style in the following by Helen Rowland in the New York Evening World:

What Every Wife Knows

Give me a man who drinks good, hot, dark, strong coffee for breakfast!

A man who smokes a good, dark, fat cigar after dinner!

You may marry your milk-faddist, or your anti-coffee crank, as you will!

But I know the magic of the coffee pot!

Let me make my Husband's coffee—and I care not who makes eyes at him!

Give me two matches a day—

One to start the coffee with, at breakfast, and one for his cigar, after dinner!

And I defy all the houris in Christendom to light a new flame in his heart!

Oh, sweet supernal coffee-pot!

Gentle panacea of domestic troubles,

Faithful author of that sweet nepenthe which deadens all the ills that married folks are heir to.

Cheery, glittering, soul-soothing, warmed hearted, inanimate friend!

What wife can fail to admit the peace and serenity she owes to you?

To you, who stand between her and all her early morning troubles—

Between her and the before-breakfast grouch—

Between her and the morning-after headache—

Between her and the cold-gray-dawn scrutiny?

To you, who supply the golden nectar that stimulates the jaded masculine soul,

Soothes the shaky masculine nerves, stirs the fagged masculine mind, inspires the slow masculine sentiment,

And starts the sluggish blood a-flowing and the whole day right!

What is it, I ask you, when he comes down to breakfast dry of mouth, and touchy of temper—

That gives him pause, and silences that scintillating barb of sarcasm on the tip of his tongue,

With which he meant to impale you?

It is the sweet aroma of the coffee-pot—the thrilling thought of that first delicious sip!

What is it, on the morning after the club dance,

That hides your weary, little, washed-out face and straggling, uncurled coiffure from his critical eyes?

It is the generous coffee-pot, standing like a guardian angel between you and him!

And in those many vital psychological moments, during the honeymoon, which decide for or against the romance and happiness of all the rest of married life—

Those critical before-breakfast moments when temperament meets temperament, and will meets "won't"—

What is it that halts you on the brink of tragedy,

And distracts you from the temptation to answer back?

It is the absorbing anxiety of watching the coffee boil!

What is it that warms his veins and soothes your nerves,

And turns all the world suddenly from a dismal gray vale of disappointment to a bright rosy garden of hope—

And starts another day gliding smoothly along like a new motor car?

What is it that will do more to transform a man from a fiend into an angel than baptism in the River Jordan?

It is the first cup of coffee in the morning!

Coffee in Dramatic Literature

Coffee was first "dramatized", so to speak, in England, where we read that Charles II and the Duke of Yorke attended the first performance of Tarugo's Wiles, or the Coffee House, a comedy, in 1667, which Samuel Pepys described as "the most ridiculous and insipid play I ever saw in my life." The author was Thomas St. Serf. The piece opens in a lively manner, with a request on the part of its fashionable hero for a change of clothes. Accordingly, Tarugo puts off his "vest, hat, perriwig, and sword," and serves the guests to coffee, while the apprentice acts his part as a gentleman customer. Presently other "customers of all trades and professions" come dropping into the coffee house. These are not always polite to the supposed coffee-man; one complains of his coffee being "nothing but warm water boyl'd with burnt beans," while another desires him to bring "chocolette that's prepar'd with water, for I hate that which is encouraged with eggs." The pedantry and nonsense uttered by a "schollar" character is, perhaps, an unfair specimen of coffee-house talk; it is especially to be noticed that none of the guests ventures upon the dangerous ground of politics.

In the end, the coffee-master grows tired of his clownish visitors, saying plainly, "This rudeness becomes a suburb tavern rather than my coffee house"; and with the assistance of his servants he "thrusts 'em all out of doors, after the schollars and customers pay."

In 1694, there was published Jean Baptiste Rosseau's comedy, Le Caffè, which appears to have been acted only once in Paris, although a later English dramatist says it met with great applause in the French capital. Le Caffè was written in Laurent's café, which was frequented by Fontenelle, Houdard de la Motte, Dauchet, the abbé Alary Boindin, and others. Voltaire said that "this work of a young man without any experience either of the world of letters or of the theater seems to herald a new genius."

About this time it was the fashion for the coffee-house keepers of Paris, and the waiters, to wear Armenian costumes; for Pascal had builded better than he knew. In La Foire Saint-Germain, a comedy by Dancourt, played in 1696, one of the principal characters is old "Lorange, a coffee merchant clothed as an Armenian". In scene 5, he says to Mlle. Mousset, "a seller of house dresses" that he has been "a naturalized Armenian for three weeks."

Mrs. Susannah Centlivre (1667?–1723), in her comedy, A Bold Stroke for a Wife, produced about 1719, has a scene laid in Jonathan's coffee house about that period. While the stock jobbers are talking in the first scene of act II, the coffee boys are crying, "Fresh Coffee, gentlemen, fresh coffee?... Bohea tea, gentlemen?"

Henry Fielding (1707–1754) published "The Coffee-House Politician, or

Comments (0)