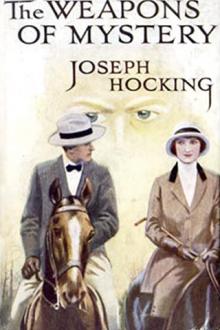

The Weapons of Mystery, Joseph Hocking [the beach read .txt] 📗

- Author: Joseph Hocking

- Performer: -

Book online «The Weapons of Mystery, Joseph Hocking [the beach read .txt] 📗». Author Joseph Hocking

"What does this mean?" asked Tom Temple, a little angrily.

At this the housekeeper became conscious and said in a hoarse whisper,

"Is she gone?"

"What? Who do you mean?" asked Tom.

"The hall lady," she said fearfully.

"We are all friends here," said Tom, and I thought I detected an amount of anxiety in his voice.

This appeared to assure the housekeeper, who got up and tried to collect her thoughts. We all waited anxiously for her to speak.

"I have stayed up late, Mr. Temple," she said to Tom, "in order to arrange somewhat for the party you propose giving on Thursday. The work had got behind, and so I asked two or three of the servants to assist me."

She stopped here, as if at a loss how to proceed.

"Go on, Mrs. Richards; we want to know all. Surely there must be something terrible to cause you all to arouse us in this way."

"I'll tell you as well as I can," said the housekeeper, "but I can hardly bear to think about it. Twas about one o'clock, and we were all very busy, when we heard a noise in the corridor outside the door. Naturally we turned to look, when the door opened and something entered."

"Well, what? Some servant walking in her sleep?"

"No, sir," said Mrs. Richards in awful tones. "It looked like a woman, very tall, and she had a long white shroud around her, and on it were spots of blood. In her hand she carried a long knife, which was also covered with blood, while the hand which held it was red. She came closer to us," she went on with a shudder, "and then stopped, lifting the terrible knife in the air. I cannot remember any more, for I was so terribly frightened. I gave an awful scream, and then I suppose I fainted."

This story was told with many interruptions, many pauses, many cries, and I saw that the faces of those around were blanched with fear.

"Do you know what it did, Simon," said Tom, turning to that worthy, "after it lifted its knife in the air?"

"She went away with a wail like," said Simon, slowly; "she opened the door and went out. An' then I tried to go to the door, and when I got there, there was nothin'."

"That is, you looked into the passage?"

Simon nodded. "And what did you think she was like?"

"Like the hall ghost, as I've heard so much about," said Simon.

"The hall ghost!" cried the ladies, hysterically. "What does that mean,

Mr. Temple?"

I do not think Tom should have encouraged their superstition by telling them, but he did. He was excited, and scarcely knew what was best to do.

"They say that, like other old houses, Temple Hall has its ghost," he said; "that she usually appears on New Year's night. If the year is to be good to those within at the time, she comes with flowers and dressed in gay attire; if bad, she is clothed in black; if there's to be death for any one, she wears a shroud. But it's all nonsense, you know," said Tom, uneasily.

"And she's come in a shroud," said the servant who had been in hysterics, "and there was spots of blood upon it, and that means that the one who dies will be murdered; and there was a knife in her hand, and that means that 'twill be done by a knife."

It would be impossible to describe the effect this girl's words made. She made the ghost very real to many, and the calamity which she was supposed to foretell seemed certain to come to pass. I looked at Gertrude Forrest and Ethel Gray, who, wrapped in their dressing-gowns, stood side by side, and I saw that both of them were terribly moved.

Voltaire and Kaffar were both there, but they uttered no word. They, too, seemed to believe in the reality of the apparition.

After a great deal of questioning on the part of the lady guests, and many soothing replies on the part of the men, something like quietness was at length restored, and many of the braver ones began to return to their rooms, until Tom and I were left alone in the servants' hall. We again questioned the servants, but with the same result, and then we went quietly up-stairs. Arriving at the landing, we saw Miss Forrest and Miss Gray leaving Mrs. Temple at the door of her room. Tom hurried to Miss Gray, and took her by the hand, while I, nothing loth, spoke to Miss Forrest.

"There's surely some trick in this," I said to her.

I felt her hand tremble in mine as she spoke. "I do not know. It seems terribly real, and I have heard of such strange things."

"But you are not afraid? If you are, I shall be up all night, and will be so happy to help you."

I thought I felt a gentle pressure of her hand, but I was not sure; but

I know that her look made me very happy as she, together with Edith

Gray, entered her room a few minutes after.

When they had gone, I said to Tom, "I am not going to bed to-night."

"No?" said Tom. "Well, I'll stay up with you."

"This ghost affair is nonsense, Tom. I hope you will not find any valuables gone to-morrow."

"Real or not," said Tom, gaily, "I'm glad it came."

"How's that?"

"It gave me nerve to pop the question," he replied. "I told my little girl just now—for she is mine now—that she wanted a strong man to protect such a weak little darling."

"And she?"

"She said that she knew of no one, whom she liked, that cared enough for her to protect her. So I told her I did, and then—well, what followed was perfectly satisfactory."

I congratulated him on his audacity, and then we spent the night in wandering about the first floor of the house, trying to find the ghost, but in vain; and when the morning came, and we all tried to laugh at the ghost, I felt that there was a deep, sinister meaning in it all, and wondered what the end would be.

CHAPTER X THE COMING OF THE NIGHTDirectly after breakfast I went away alone. I wanted to get rid of an awful weight which oppressed me. I walked rapidly, for the morning was cold. I had scarcely reached the park gates, however, when a hand touched me. I turned and saw Kaffar.

"I hope your solitary walk is pleasant," he said, revealing his white teeth.

"Thank you," I replied coldly.

I thought he was going to leave me, but he kept close by my side, as if he wanted to say something. I did not encourage him to speak, however; I walked rapidly on in silence.

"Temple Hall is a curious place," he said.

"Very," I replied.

"So different from Egypt—ah, so different. There the skies are bright, the trees are always green. There the golden sandhills stretch away, the palm trees wave, the Nile sweeps majestic. There the cold winds scarcely ever blow, and the people's hearts are warm."

"I suppose so."

"There are mysteries there, as in Temple Hall, Mr. Blake; but mysteries are sometimes of human origin."

As he said this, he leered up into my face, as if to read my thoughts; but I governed my features pretty well, and thus, I think, deceived him.

"Perhaps you know this?" he said.

"No," I replied. "I am connected with no mysteries."

"Not with the appearance of the ghost last night?"

I looked at him in astonishment. The insinuation was so far from true that for the moment I was too surprised to speak.

He gave a fierce savage laugh, and clapped his hands close against my face. "I knew I was right," he said; and then, before I had time to reply, he turned on his heel and walked away.

Things were indeed taking curious turns, and I wondered what would happen next. What motive, I asked, could Kaffar have in connecting me with the ghost, and what was the plot which was being concocted? There in the broad daylight the apparition seemed very unreal. The servants, alone in the hall at midnight, perhaps talking about the traditional ghost, could easily have frightened themselves into the belief that they had seen it. Or perhaps one of their fellow-servants sought to play them a trick, and ran away when they saw what they had done. I would sift a little deeper. I immediately retraced my steps to the house, where meeting Tom, I asked him to let me have Simon Slowden and a couple of dogs, as I wanted to shoot a few rabbits. This was easily arranged, and soon after Simon and I were together. Away on the open moors there was no fear of eavesdroppers; no one could hear what we said.

"Simon," I said, after some time, "have you thought any more of the wonderful ghost that you saw last night?"

Instantly his face turned pale, and he shuddered as if in fear. At any rate, the ghost was real to him.

"Yer honour," he said, "I don't feel as if I can talk about her. I've played in 'Amlet, yer honour, along with Octavius Bumpus's travellin' theatre, and I can nail a made-up livin' ghost in a minnit; but this ghost didn't look made up. There was no blood, yer honour; she looked as if she 'ad bin waccinated forty times."

"And were the movements of her legs and arms natural?"

"No j'ints, Master Blake. She looked like a wooden figger without proper j'ints! Perhaps she 'ad a few wire pins in her 'natomy; but no j'ints proper."

"So you believe in this ghost?"

"Can't help it, yer honour."

"Simon, I don't. There's some deep-laid scheme on foot somewhere; and I think I can guess who's working it."

Simon started. "You don't think that 'ere waccinatin', sumnamblifyin' willain 'ev got the thing in 'and?"

I didn't speak, but looked keenly at him.

At first he did nothing but stare vacantly, but presently a look of intelligence flashed into his eyes. Then he gave a shrug, as if he was disgusted with himself, which was followed by an expression of grim determination.

"Master Blake," he said solemnly, "it's that waccinatin' process as hev done it. Simon Slowden couldn't hev bin sich a nincompoop if he hadn't bin waccinated 'gainst whoopin' cough, measles, and small-pox. Yer honour," he continued, "after I wur waccinated I broke out in a kind of rash all over, and that 'ere rash must have robbed me of my senses; but I'm blowed—There, I can't say fairer nor that."

"Why, what do you think?"

"I daren't tell you, yer honour, for fear I'll make another mistake. I thowt, sur, as it would take a hangel with black wings to nick me like this 'ere, and now I've bin done by somebody; but it's the waccinatin', yer honour—it's the waccination. In the Proverbs of Job we read, 'fool and his money soon parted,' and so we can see 'ow true the teachin' is to-day."

"But what is to be done, Simon?"

Simon shook his head, and then said solemnly, "I'm away from my bearin's, sur. I thought when I wur done the last time it should be the last time. It wur in this way, sur. I was in the doctor's service as waccinated me. Says he, when he'd done, 'Simon, you'll never have small-pox now.' 'Think not?' says I. 'Never,' says he; and when Susan the

Comments (0)