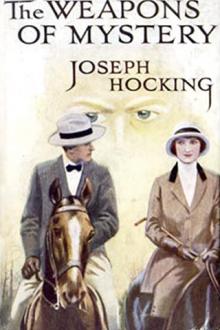

The Weapons of Mystery, Joseph Hocking [the beach read .txt] 📗

- Author: Joseph Hocking

- Performer: -

Book online «The Weapons of Mystery, Joseph Hocking [the beach read .txt] 📗». Author Joseph Hocking

"Are you well, Mr. Blake?" she asked again. "You look strange."

"Well, well," I remember saying. Then we caught sight of three people riding.

"Hurrah!" I cried, "there they are."

I could see I was surprising Miss Forrest more and more, but she did not speak again. Pride and vexation seemed to overcome her other feelings, and so silently we rode on together until we rejoined our companions.

"Ha, Justin!" cried Tom, "we did not expect to see you just yet Surely something's the matter?"

"Oh no," I replied, when, looking at Herod Voltaire, I saw a ghastly smile wreathe his lips, and then I felt my burden gone. Evidently by some strange power, at which I had laughed, he had again made me obey his will, and when he had got me where he wanted me, he allowed me to be free. No sooner did I feel my freedom than I was nearly mad with rage. I had been with the woman I wanted, more than anything else, to accompany, we had been engaged in a conversation which was getting more and more interesting for me, and then, for no reason save this man's accursed power, I had come back where I had no desire to be.

I set my teeth together and vowed to be free, but, looking again at Voltaire's eyes, my feelings underwent another revulsion. I trembled like an aspen leaf. I began to dread some terrible calamity. Before me stretched a dark future. I seemed to see rivers of blood, and over them floated awful creatures. For a time I thought I was disembodied, and in my new existence I did deeds too terrible to relate. Then I realized a new experience. I feared Voltaire with a terrible fear. Strange forms appeared to be emitted from his eyes, while to me his form expanded and became terrible in its mien.

I knew I was there in a Yorkshire road, riding on a high-blooded horse; I knew the woman I loved was near me; and yet I was living a dual life. It was not Justin Blake who was there, but something else which was called Justin Blake, and the feelings that possessed me were such as I had never dreamed of. And yet I was able to think; I was able to connect cause and effect. Indeed, my brain was very active, and I began to reason out why I should be so influenced, and why I should act so strangely.

The truth was, and I felt sure of it as I rode along, I was partly mesmerized or hypnotized, whatever men may please to call it. Partly I was master over my actions, and partly I was under an influence which I could not resist. Strange it may appear, but it is still true, and so while one part of my being or self was realizing to a certain extent the circumstances by which I was surrounded, the other enslaved part trembled and feared at some dreadful future, and felt bound to do what it would fain resist.

This feeling possessed me till we arrived at Temple Hall, when I felt free, and, as if by the wave of some magical wand, Justin Blake was himself again.

Instead of following the ladies into the house, I followed the horses to the stables. I thought I might see Simon Slowden, who I was sure would be my friend, and was watching Kaffar closely, but I could not catch sight of him. Herod Voltaire came up to me, however, and hissed in my ear—

"Do you yield to my power now?"

I answered almost mechanically, "No."

"But you will," he went on. "You dared to follow me to yonder lake, but you found you could not ride alone with her. How terrible it must be to have to obey the summons of the devil, and so find out the truth that while two is company, five is none!"

I began to tremble again.

He fixed his terrible eye upon me, and said slowly and distinctly, "Justin Blake, resistance is useless. I have spent years of my life in finding out the secrets of life. By pure psychology I have obtained my power over you. You are a weaker man than I—weaker under ordinary circumstances. You would be swayed by my will if I knew no more the mysteries of the mind than you, because as a man I am superior to you—superior in mind and in will-force; but by the knowledge I have mentioned I have made you my slave."

I felt the truth of his words. He was a stronger man than I naturally, while by his terrible power I was rendered entirely helpless. Still, at that very moment, the inherent obstinacy of my nature showed itself.

"I am not your slave," I said.

"You are," he said. "Did you feel no strange influences coming back just now? Was not Herod Voltaire your master?"

I was silent.

"Just so," he answered with a smile; "and yet I wish to do you no harm. But upon this I do insist. You must leave Temple Hall; you must allow me to woo and to win Miss Gertrude Forrest."

"I never will," I cried.

"Then," said he, jeeringly, "your life must be ruined. You must be swept out of the way, and then, as I told you, I will take this dainty duck from you, I will press her rosy lips to mine, and—"

"Stop!" I cried; "not another word;" and, seizing him by the collar, I shook him furiously. "Speak lightly of her," I continued, "and I will thrash you like a dog, as well as that cur who follows at your heels."

For a moment my will had seemed to gain the mastery over him. He stared at me blankly, but only for a moment, for soon his light eyes glittered; and then, as Kaffar came up by his side, my strength was gone, my hands dropped by my side, and unheeding the cynical leer of the Egyptian, or the terrible look of his friend, I walked into the house like one in a dream.

CHAPTER VIII DARKNESS AND LIGHTDuring the next few days there was but little to record. The party evidently forgot mesmerism and thought-reading, and seemingly enjoyed themselves without its assistance. The young men and women walked together and talked together, while the matrons looked complacently on. During the day there was hunting, skating, and riding, while at night there was story-telling, charades, games of various sorts, and dancing. Altogether, it was a right old-fashioned, unconventional English country party, and day by day we got to enjoy ourselves more, because we learned to know each other better.

Perhaps, however, I am using a wrong expression. I ought not to have said "we." I cannot say that I enjoyed myself very much. My life was strange and disappointing. More than that, the calamities I dreaded did not take place, but the absence of those calamities brought me no satisfaction. And thus, while all the rest laughed and were joyful, I was solitary and sad. Once or twice I thought of leaving Temple Hall, but I could not bring myself to do so. I should be leaving the woman I was each day loving more and more, to the man who knew no honour, no mercy, no manliness.

During these days I was entirely free from Voltaire's influence, as free as I was before I saw him. He always spoke to me politely, and to a casual observer his demeanour towards me was very friendly. Kaffar, on the other hand, treated me very rudely. He often sought to turn a laugh against me; he even greeted me with a sneer. I took no notice of him, however—never replied to his insulting words; and this evidently maddened him. The truth was, I was afraid lest there should be some design in Voltaire's apparent friendliness and Kaffar's evident desire to arouse enmity, and so I determined to be on my guard.

I was not so much surprised at my freedom from the influence he had exercised over me the day after I had placed myself under his power, and for a reason that was more than painful to me. Miss Forrest avoided ever meeting me alone, never spoke to me save in monosyllables, and was cold and haughty to me at all times. Many times had I seen her engaged in some playful conversation with some members of the party; but the moment I appeared on the scene her smile was gone, and, if opportunity occurred, she generally sought occasion to leave. Much as I loved her, I was too proud to ask a reason for this, and so, although we were so friendly on Christmas Day, we were exceedingly cold and distant when New Year's Eve came. This, as may be imagined, grieved me much; and when I saw Voltaire's smile as he watched Miss Forrest repel any attempt of mine to converse with her, I began to wish I had never set my foot in Temple Hall.

And yet I thought I might be useful to her yet. So I determined to remain in Yorkshire until she returned to London, and even then I hoped to be able to shield her from the designs which I was sure Voltaire still had.

New Year's Day was cold and forbidding. The snow had gone and the ice had melted; but the raw, biting wind swept across moor and fen, forbidding the less robust part of the company to come away from the warm fires.

I had come down as usual, and, entering the library, I found Miss

Forrest seated.

"I wish you a happy new year, Miss Forrest," I said. "May it be the happiest year you have ever known." She looked around the room as if she expected to see some one else present; then, looking up at me, she said, with the happy look I loved to see, "And I heartily return your wish, Mr. Blake."

There was no coldness, no restraint in her voice. She spoke as if she was glad to see me, and wanted me to know it. Instantly a burden rolled away from my heart, and for a few minutes I was the happiest of men. Presently I heard voices at the library door, and immediately Miss Forrest's kindness and cheerfulness vanished, and those who entered the room must have fancied that I was annoying her with my company. I remained in the room a few minutes longer, but she was studiously cold and polite to me, so that when I made a pretence of going out to the stables to see a new horse Tom Temple had bought, I did so with a heavy heart.

I had no sooner entered the stable-yard than Simon Slowden appeared, and beckoned to me.

"I looked hout for yer honour all day yesterday," he said, "but you lay like a hare in a furze bush. Things is looking curious, yer honour."

"Indeed, Simon. How?"

"Can 'ee come this yer way a minit, yer honour?" "Certainly," I said, and followed him into a room over the stables. I did not like having confidences in this way; but my brain was confused, and I could not rid myself from the idea that some plot was being concocted against me.

Simon looked around to make sure there were no eavesdroppers; then he said, "There's a hancient wirgin 'ere called Miss Staggles, ain't there, Mr. Blake?"

"There is. Why?"

"It's my belief as 'ow she's bin a waccinated ten times, yer honour."

"Why, Simon?"

"Why, she's without blood or marrow, she is; and as for flesh, she ain't got none."

"Well, what for that?"

"And not honly that," he continued, without heeding my question, "she hain't a got a hounce of tender feelin's in her natur. In my opinion, sur, she's a witch, she is, and hev got dealin's with the devil."

"And what for all this?" I said. "Surely you haven't taken me up here to give me your impressions concerning Miss Staggles?"

"Well, I hev partly, yer honour. The truth is"—here he sunk his voice to a whisper—"she's very thick with that willain with a hinfidel's name. They're in league, sur." "How do you know?"

"They've bin a-promenadin' together nearly every day since Christmas; and when a feller like that 'ere Woltaire goes a-walkin' with a creature like that hancient wirgin on his arm, then I think there must be somethin' on board."

"But this is purely surmise, Simon. There is no reason why Miss Staggles and Mr. Voltaire may not walk together."

Comments (0)