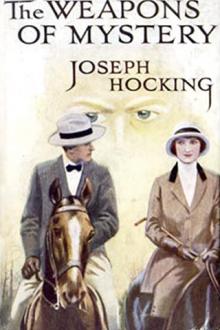

The Weapons of Mystery, Joseph Hocking [the beach read .txt] 📗

- Author: Joseph Hocking

- Performer: -

Book online «The Weapons of Mystery, Joseph Hocking [the beach read .txt] 📗». Author Joseph Hocking

When I awoke to consciousness I was in my bedroom. For some time I could not gather up my scattered senses; my mind refused to exercise its proper functions. Presently I heard some one speak.

"I had no idea he was so far gone," a voice said. "You see, his power of resistance is very great, and it needed four times the magnetism to bring him under that it did your servant."

"I'm sorry you experimented on him at all," said another voice.

"Oh, I can assure you no harm's done. There, you see, he's coming to."

I felt something cold at my temples, then a strange shivering sensation passed over me, and I was awake.

Voltaire, Kaffar, Tom Temple, and Simon Slowden were in the room. "How do you feel, Mr. Blake?" asked Voltaire, blandly.

I lifted my eyes to his, and felt held by a strange power. "I'm all right," I said almost mechanically, at the same time feeling as if I was under the influence of a charm.

"Then," said Voltaire, "I will leave you. Good-night."

Immediately he left, followed by Kaffar, I experiencing a sense of relief. "Did I do anything very foolish?" I asked, recollecting the events of the evening.

"Oh no, Justin," replied Tom. "And yet that Voltaire is a terrible fellow. Half the young ladies in the room were nearly as much mesmerized as you were. You acted in pretty nearly the same way as Simon here, but nothing else. Do you feel quite right?"

"I am awfully weak," I said, "and cold shivers creep down my legs."

"You were such a long time under the influence, whatever it is," said

Tom. "But you'll go back to the drawing-room?"

"No; I don't feel up to it. But don't you remain. I'm feeling shaky, but

I shan't mind a bit if you'll let Simon remain with me."

And so Tom left me with Simon. "Do you feel shaky and shivery, Simon?" I asked.

"Not a bit on it, sir," was the reply. "Never felt better. But 'tween you and me and the gatepost, yon hinfidel hain't a served me like he hev you. I don't like the look o' things, yer honour."

"Why, Simon?"

"Why, sir, 'tain't me as ought to tell, and yet I don't feel comfortable. I wish I could 'a had a confabulation with yer afore this performance come off. I hain't got no doubts in my mind but that hinfidel and his dootiful brother hev got dealin's with the devil."

Simon rose and went to the door, opened it, and peered cautiously around. "That Egyptian is a watcher," he said grimly, "and I don't like either of 'em."

"What's the matter, Simon?"

"Why, this yer morning, I wur exchangin' a few pleasant remarks with one of the maid-servants, when I hears the Egyptian say, 'It's gwine beautiful.' 'How?' says t'other. 'He'll nibble like hanything,' was the answer, and then I hearn a nasty sort o' laugh. Soon after, I see you with a bootiful young lady, and I see that hinfidel a-watchin' yer, with a snaky look in his eyes. And so I kep on watchin', and scuse me, yer honour, but I can guess as 'ow things be, and I'm fear'd as 'ow this waccination dodge is a trick o' this 'ere willain."

"Explain yourself, Simon."

"Well, sir, I knows as 'ow you've only bin yer one day, but I could see in a minit as 'ow you was a smitten with a certain young lady, and I can see, too, as 'ow that white-eyed willain is smitten in the same quarter, and he sees 'ow things be, and he means business."

It was by no means pleasant to hear my affairs talked of in this way, and it was a marvel to me how Simon could have learnt so much, but I have found that a certain class of English servant seems to find out everything about the house with which they are connected, and I am afraid I was very careless as to who saw the state of my feelings. At any rate, Simon guessed how things were, and, more than that, he believed that Voltaire had some sinister design against me.

"What do you mean by what you call the vaccination dodge?" I asked, after a second's silence.

"Scuse me, yer honour, but since that doctor waccinated me and nearly killed me by it, tough as I be, I come to call all tomfoolery by the same name. I've been in theatres, yer honour, and played in pieces, and I've known the willain in the play get up a shindy like this. I knows they're on'y got up to 'arrow up the feelin's o' tender females; but I'm afeared as 'ow this Voltaire 'ev got somethin' in his head, a-concoctin' like."

"Nonsense, Simon," I said. "You are thinking about some terrible piece you've acted in, and your imagination is carrying away your judgment."

"I hope as 'ow 'tis, sur; but I don't think so. If you chop me up, sur, you'll not find sixpenno'th of imagination in my carcase, but I calcalate I'm purty 'eavy wi' judgment. Never mind, sur; Simon Slowden is in the 'ouse, if you should want help, sur."

I did not feel much inclined to talk after this, and so, dismissing Simon, I began to think of how matters stood. Certainly everything was strange. Everything, too, had been done in a hurry. It seemed to me I had lived a long life in twenty-four hours. I had fallen in love, I had made an enemy, and I had matched myself against men who possessed a knowledge of some of the secret forces of life, without ever calculating my own strength. And yet I seemed to be beating the air. Were not my thoughts concerning Voltaire's schemes about Miss Forrest all fancy? Was not I the victim of some Quixotic ideas? Was not the creation of Cervantes' brain about as sensible as I? Surely I, a man of thirty, ought to know better? And yet some things were terribly real. My love for Gertrude Forrest was real; my walk and talk with her that day were real. Ay, and the hateful glitter of Voltaire's eyes was real too; his talk with Kaffar behind the shrubs the night before was real. The biological or hypnotic power that I had felt that very night was real, and, above all, a feeling of dread that had gripped my being was real. I could not explain it, and I could not throw it off, but ever since I had awoke out of my mesmeric sleep, or whatever the reader may be pleased to call it, I felt numbed; weights seemed to hang on my limbs, and my whole being was in a kind of torpor.

I went to bed at length, however, and, after an hour's tossing, fell asleep, from which I did not wake until ten o'clock next morning. I found, on descending, that nearly all had breakfasted, but the few with whom I spoke were very kind and pleasant towards me. I had no sooner finished breakfast than I met Miss Forrest, and entered into conversation with her. Once with her, all my dreads and fears vanished. Her light eyes and merry laugh drove away dull care, and soon I was in Paradise. Surely I could not be mistaken! Surely the quivering hand, the tremulous mouth, the downcast eye, meant something! Surely she need not be agitated at meeting me, unless she took a special interest in me—unless, indeed, she felt as I felt! At any rate, it were heaven to think so. We had been talking I should think ten minutes, when Tom Temple came towards us.

"Say, Justin, my boy," he said, "what do you say to a gallop of four?"

"Who are the four?" I asked.

"Miss Forrest, Miss Edith Gray, Justin Blake, and—myself," was the reply.

"I shall be more than delighted if Miss Forrest will—" I did not finish the sentence. At that moment I felt gripped by an unseen power, and I was irresistibly drawn towards the door. I muttered something about forgetting, and then, like a man in a sleep, I put on my hat and coat and went out, I know not where.

I cannot remember much about the walk. It was very cold, and my feet crunched the frozen snow; but I thought little of it—I was drawn on and on by some secret power. I was painfully aware that Miss Forrest must think I was acting strangely and discourteously, and once or twice I essayed to go back to her, but I could not I was drawn on and on, always away from the house.

At length I entered a fir wood, and I began to feel more my real self. I saw the dark pines, from whose prickly foliage the snow crystals were falling; I realized a stern beauty in the scene; but I had not time to think about it. I felt I was near the end of my journey, and I began to wonder at my condition. I had not gone far into the wood before I stopped and looked around me. The influence had gone, and I was free; but from behind one of the trees stepped out a man, and the man was—Herod Voltaire!

"Good-morning, Mr. Justin Blake," he said blandly.

"Why have you brought me here?" I asked savagely.

He smiled blandly. "You will admit I have brought you here, then?" he said. "Ah, my friend, it is dangerous to fight with a man when you don't know his weapons."

"I want to know what this means?" I said haughtily.

"Not so fast," he sneered. "Come down from that high horse and let's talk quietly. Yes, I've no doubt you would have enjoyed a ride with a certain lady better than the lonely walk you have had; but, then, you know the old adage, 'Needs must when the devil drives.'"

"And so you've admitted your identity!" I said. "Well, I don't want your society; say what you want to say, or I'm going back."

"Yes," he said, revealing his white teeth, "I am going to say what I want to say, and you are not going back until you have heard it, and, more than that, promised to accede to it."

Again I felt a cold shiver creep over me, but I put on a bold face, and said, "It always takes two to play at any game."

"Yes it does, Mr. Blake, and that you'll find out. You feel like defying me, don't you? Just so; but your defiance is useless. Did you not come here against your will? Are you not staying here now against your will? Look here, my man, you showed your hand immediately you came, and you've been playing your game without knowing the trump cards. It looked very innocent to be mesmerized last night, didn't it? Oh, mesmerism is a vulgar affair; but there was more than mesmerism realized last night. I played three trump cards last night, Mr. Justin Blake. The Egyptian story was one, the thought-reading was the second, the animal and mental magnetism was the third. I had tested my opponent before, and knew just how to play. When I took the last trick, you became mine—mine, body and soul!"

I still defied him, and laughed scornfully into his face.

"Yes, you laugh," he said; "but I like your English adages, and one is this, 'Those laugh best who win.' But come," he said, altering his tone, "you are in my power. By that one act last night you placed yourself in my power, and now you are my slave. But I am not a hard master. Do as I wish you, and I shall not trouble you."

"I defy you!" I cried. "I deny your power!"

"Do you?" he said. "Then try and move from your present position."

I had been leaning against a tree, and tried to move; but I could not. I was like one fastened to the ground.

He laughed scornfully. "Now do you believe?" he said.

I was silent.

"Yes," he said, "you may well be silent, for what I say is true. And now," he continued, "I promise not to use my power over you on one condition."

"Name it," I said.

"I will name it. It is this. You must give up all thoughts, all hopes, all

Comments (0)