The Lust of Hate, Guy Newell Boothby [essential books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Guy Newell Boothby

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lust of Hate, Guy Newell Boothby [essential books to read .txt] 📗». Author Guy Newell Boothby

came out. The mere sight of the man I hated shattered all my plans in an

instant. In the presence of the extraordinary individual accompanying

him I had not sufficient pluck to cry “engaged”; so, when the

commissionaire hailed me, there was nothing for it but to drive across

the road and pull up alongside the pavement, as we had previously

arranged.

“You’re in luck’s way, Bartrand,” cried Nikola, glancing at my

horse, which was tossing his head and pawing the ground as if eager

to be off again; “that’s a rare good nag of yours, cabby. He’s worth

an extra fare.”

I grunted something in reply, I cannot remember what. The mere

sight of Bartrand standing there on the pavement scanning the horse,

had roused all my old antipathy; and, as I have said, my good

resolves were cast to the winds like so much chaff.

“Well, for the present, au revoir, my dear fellow,” said

Nikola, shaking hands with his victim. “I will meet you at the house

in half-an-hour, and if you care about it you can have your revenge

then; now you had better be going. Twenty-eight, Saxeburgh Street,

cabby, and don’t be long about it.”

I touched my hat and opened the apron for Bartrand to step inside.

When he had done so he ordered me to lower the glass, and not be long

in getting him to his destination or I’d hear of it at the other end.

He little thought how literally I might interpret the command.

Leaving Nikola standing on the pavement looking after us, I shook

up my horse and drove rapidly down the street. My whole body was

tingling with exultation; but that it would have attracted attention

and spoiled my revenge, I felt I could have shouted my joy aloud.

Here I was with my enemy in my power; by lifting the shutter in the

roof of the cab I could see him lolling inside—thinking, doubtless,

of his wealth, and little dreaming how close he was to the poor

fellow he had wronged so cruelly. The knowledge that by simply

pressing the spring under my hand I could destroy him in five

seconds, and then choosing a quiet street could tip him out and be

done with him for ever, intoxicated me like the finest wine. No one

would suspect, and Nikola, for his own sake, would never betray me.

While I was thinking in this fashion, and gloating over what I was

about to do, I allowed my horse to dawdle a little. Instantly an

umbrella was thrust up through the shutter and I was ordered, in the

devil’s name, to drive faster.

“Ah! my fine fellow,” I said to myself, “you little know how near

you are to the master by whom you swear. Wait a few moments until

I’ve had a little more pleasure out of your company, and then we’ll

see what I can do for you.”

On reaching Piccadilly I turned west, and for some distance

followed the proper route for Saxeburgh Street. All the time I was

thinking, thinking, and thinking of what I was about to do. He was at

my mercy; any instant I could make him a dead man, and the cream of

the jest was that he did not know it. My fingers played with the

fatal knob, and once I almost pressed it. The touch of the cold steel

sent a thrill through me, and at the same instant one of the most

extraordinary events of my life occurred. I am almost chary of

relating it, lest my readers may feel inclined to believe that I am

endeavouring to gull them with the impossible. But, even at the risk

of that happening, I must tell my story as it occurred to me. As I

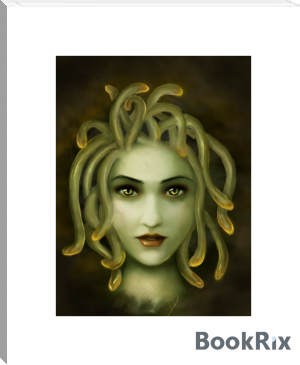

put my hand for the last time upon the knob there rose before my

eyes, out of the half dark, a woman’s face, and looked at me. At

first I could scarcely believe my own eyes. I rubbed them and looked

again. It was still there, apparently hanging in mid-air above the

horse I was driving. It was not, if one may judge by the photographs

of famous beauties, a perfect face, but there was that in it that

made it to me the most captivating I had ever seen in my life—I

refer to the expression of gentleness and womanly goodness that

animated it. The contour of the face was oval, the mouth small and

well-shaped, and the eyes large, true, and unflinching. Though it

only appeared before me for a few seconds, I had time to take

thorough stock of it, and to remember every feature. It seemed to be

looking straight at me, and the mouth to be saying as plainly as any

words could speak—“Think of what you are doing, Gilbert

Pennethorne; remember the shame of it, and be true to yourself.” Then

she faded away; and, as she went, a veil that had been covering my

eyes for months seemed now to drop from them, and I saw myself for

what I really was—a coward and a would-be murderer.

We were then passing down a side street, in which—fortunately

for what I was about to do—there was not a single person of any sort

to be seen. Happen what might, I would now stop the cab and tell the

man inside who I was and with what purpose I had picked him up. Then

he should go free, and in letting him understand that I had spared

his life I would have ray revenge. With this intention I pulled my

horse up, and, unwrapping my rug from my knees, descended from my

perch. I had drawn up the glass before dismounting, the better to be

able to talk to him.

“Mr. Bartrand,” I said, when I had reached the pavement, at the

same time pulling off my false beard and my sou’wester, “this

business has gone far enough, and I am now going to tell you who I am

and what I wanted with you. Do you know me?”

Either he was asleep or he was too surprised at seeing me before

him to speak, at any rate he offered no reply to my question.

“Mr. Bartrand,” I began again, “I ask you if you are aware who I

am?”

Still no answer was vouchsafed to me, and immediately an overwhelming

fear took possession of me. I sprang upon the step and tore open the

apron. What I saw inside made me recoil with terror. In the corner, his

head thrown back and his whole body rigid, lay the unfortunate man I had

first determined to kill, but had since decided to spare. I ran my

hands, all trembling with terror, over his body. The man was dead—and I

had killed him. By some mischance I must have pressed the spring which

opened the valve, and thus the awful result had been achieved. Though

years have elapsed since it happened, I can feel the agony of that

moment as plainly now as if it was but yesterday.

When I understood that the man was really dead, and that I was his

murderer—branded henceforth with the mark of Cain—I sat down on the

pavement in a cold sweat of terror, trembling in every limb. The face

of the whole world had changed within the past few minutes—now I

knew I could never be like other men again. Already the fatal noose

was tightening round my neck.

While these thoughts were racing through my brain, my ears, now

preternaturally sharp, had detected the ring of a footstep on the

pavement a hundred yards or so away. Instantly I sprang to my feet,

my mind alert and nimble, my whole body instinct with the thought of

self-preservation. Whatever happened I must not be caught,

red-handed, with the body of the murdered man in my possession. At

any risk I must rid myself of that, and speedily, too.

Climbing to my perch again I started my horse off at a rapid pace

in the same direction in which I had been proceeding when I had made

my awful discovery. On reaching the first cross-roads I branched off

to the right, and, discovering that to be a busy thoroughfare, turned

to the left again. Never before had my fellow-man inspired me with

such terror. At last I found a deserted street, and was in the act of

pressing the lever with my foot when a door in a house just ahead of

me opened, and a party of ladies and gentlemen issued from it. Some

went in one direction, others in a contrary, and I was between both.

To drop the body where they could see it would be worse than madness,

so, almost cursing them for interrupting me, I lashed my horse and

darted round the first available corner. Once more I found a quiet

place, but this time I was interrupted by a cab turning into the

street and coming along behind me. The third time, however, was more

successful. I looked carefully about me. The street was empty in

front and behind. On either side were rows of respectable

middle-class houses, with never a light in a window or a policeman to

be seen.

Trembling like a leaf, I stopped the cab, and when I had made sure

that there was no one looking, placed my foot upon the lever. So

perfect was the mechanism that it acted instantly, and, what was

better still, without noise. Next moment Bartrand was lying upon his

back in the centre of the road. As soon as his weight released it the

bottom of the vehicle rose, and I heard the spring click as it took

its place again. Before I drove on I turned and looked at him where

he lay so still and cold on the pure white snow, and thought of the

day at Markapurlie, when he had turned me off the station for wanting

to doctor poor Ben Garman, and also of the morning when I had

denounced him to the miners on the Boolga Bange, after I had

discovered that he had stolen my secret and appropriated my wealth.

How little either of us thought then what the end of our hatred was

to be! If I had been told on the first day we had met that I should

murder him, and that he would ultimately be found lying dead in the

centre of a London street, I very much doubt if either of us would

have believed it possible. But how horribly true it was!

As to what I was now, there could be no question. The ghastly

verdict was self-evident, and the word rang in my brain with a

significance I had never imagined it to possess before. It seemed to

be written upon the houses, to be printed upon the snow-curdled sky.

Even the roll of the wheels beneath me proclaimed me a murderer.

Until that time I had had no real conception of what that grisly word

meant. Now I knew it for the most awful in the whole range of our

English language.

All this time I had been driving aimlessly on and on, having no

care where I went, conscious only that I must put as great a

distance as possible between myself and the damning evidence of my

crime. Then a reaction set in, and I became aware that to continue

driving in this half-coherent fashion was neither politic nor

sensible, so I pulled myself together and tried to think what I had

better do. The question for my consideration was whether I should

hasten to Hogarth Square as arranged and hand the cab over to Nikola,

or whether I should endeavour to dispose of it in some other way, and

Comments (0)