The Lust of Hate, Guy Newell Boothby [essential books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Guy Newell Boothby

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lust of Hate, Guy Newell Boothby [essential books to read .txt] 📗». Author Guy Newell Boothby

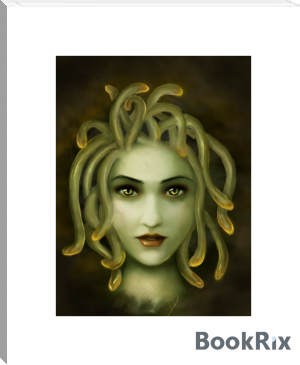

there, gazing across the sea, was the same woman’s face I had seen

suspended in mid-air above my cab on the previous night. Astonishing

as it may seem, there could be no possible doubt about it—I

recognised the expressive eyes, the sweet mouth, and the soft, wavy

hair as plainly as if I had known her all my life long.

Thinking it was still only a creation of my own fancy, and that in

a moment it would fade away as before, I stared hard at it, resolved,

while I had the chance, to still further impress every feature

upon my memory. But it did not vanish as I expected. I rubbed my eyes

in an endeavour to find out if I were awake or asleep, but that made

no difference. She still remained. I was quite convinced by this

time, however, that she was flesh and blood. But who could she be,

and where had I really seen her face before? For something like five

minutes I watched her, and then for the first time she looked down at

the deck where I sat. Suddenly she caught sight of me, and almost at

the same instant I saw her give a little start of astonishment.

Evidently she had also seen me in some other place, but could no more

recall it than myself.

As soon as she had recovered from her astonishment she glanced

round the waste of water again and then moved away. But even when she

had left me I could not for the life of me rid myself of my feeling

of astonishment. I reviewed my past life in an attempt to remember

where I had met her, but still without success. While I was

wondering, my friend the chief steward came along the deck again. I

accosted him, and asked if he could tell me the name of the lady with

the wavy brown hair whom I could see talking to the captain at the

door of the chart house. He looked in the direction indicated, and

then said:

“Her name is Maybourne—Miss Agnes Maybourne. Her father is a big

mine owner at the Cape, so I’m told. Her mother died about a year

ago, I heard the skipper telling a lady aft this morning, and it

seems the poor young thing felt the loss terribly. She’s been home

for a trip with an old uncle to try and cheer her up a bit, and now

they are on their way back home again.”

“Thank you very much,” I said. “I have been puzzling over her face

for some time. She’s exactly like someone I’ve met some time or

other, but where, I can’t remember.”

On this introduction the steward favoured me with a long account

of a cousin of his—a steward on board an Atlantic liner—who, it

would appear, was always being mistaken for other people; to such a

length did this misfortune carry him that he was once arrested in

Liverpool on suspicion of being a famous forger who was then at

large. Whether he was sentenced and served a term of penal servitude,

or whether the mistake was discovered and he was acquitted, I cannot

now remember; but I have a faint recollection that my friend

described it as a case that baffled the ingenuity of Scotland Yard,

and raised more than one new point of law, which he, of course, was

alone able to set right in a satisfactory manner.

Needless to say, Miss Maybourne’s face continued to excite my

wonder and curiosity for the remainder of the afternoon; and when I

saw her the following morning promenading the hurricane deck in the

company of a dignified grey-haired gentleman, with a clean-shaven,

shrewd face, who I set down to be her uncle, I discovered that my

interest had in no way abated. This wonderment and mystification kept

me company for longer than I liked, and it was not until we were

bidding “good-bye” to the Channel that I determined to give up

brooding over it and think about something else.

Once Old England was properly behind us, and we were out on the

open ocean, experiencing the beauties of a true Atlantic swell, and

wondering what our portion was to be in the Bay of Biscay, my old

nervousness returned upon me. This will be scarcely a matter for

wonder when you reflect that every day we were drawing nearer our

first port of call, and at Teneriffe I should know whether or not the

police had discovered the route I had taken. If they had, I should

certainly be arrested as soon as the vessel came to anchor, and be

detained in the Portuguese prison until an officer should arrive from

England to take charge of me and conduct me home for trial. Again and

again I pictured that return, the mortification of my relatives, and

the excitement of the Press; and several times I calmly deliberated

with myself as to whether the best course for me to pursue would not

be to drop quietly overboard some dark night, and thus prevent the

degradation that would be my portion if I were taken home and placed

upon my trial. However, had I but known it, I might have spared

myself all this anxiety, for the future had something in store for me

which I had never taken into consideration, and which was destined to

upset all my calculations in a most unexpected fashion.

How strange a thing is Fate, and by what small circumstances are

the currents of our lives diverted! If I had not had my match-box in

my pocket on the occasion I am about to describe, what a very

different tale I should have had to tell. You must bear with me if I

dwell upon it, for it is the one little bit of that portion of my

life that I love to remember. It all came about in this way: On the

evening in question I was standing smoking against the port bulwarks

between the fore rigging and the steps leading to the hurricane deck.

What the exact time was I cannot remember. It may have been eight,

and it might possibly have been half-past; one thing, at any rate, is

certain: dinner was over in the saloon, for some of the passengers

were promenading the hurricane deck. My pipe was very nearly done,

and, having nothing better to do, I was beginning to think of turning

in, when the second officer came out of the alley way and asked me

for a match. He was a civil young fellow of two or three-and-twenty,

and when I had furnished him with what he wanted, we fell into

conversation. In the course of our yarning he mentioned the name of

the ship upon which he had served his apprenticeship. Then, for the

first time for many years, I remembered that I had a cousin who had

also spent some years aboard her. I mentioned his name, and to my

surprise he remembered him perfectly.

“Blakeley,” he cried; “Charley Blakeley, do you mean? Why, I knew

him as well as I knew any man! As fine a fellow as ever stepped. We

made three voyages to China and back together. I’ve got a photograph

of him in my berth now. Come along and see it.”

On this invitation I followed him from my own part of the vessel,

down the alley way, past the engine-room, to his quarters, which were

situated at the end, and looked over the after spar deck that

separated the poop from the hurricane deck. When I had seen the

picture I stood at the door talking to him for some minutes, and

while thus engaged saw two ladies and a gentleman come out of the

saloon and go up the ladder to the deck above our heads. From where I

stood I could hear their voices distinctly, and could not help

envying them their happiness. How different was it to my miserable

lot!

Suddenly there rang out a woman’s scream, followed by another, and

then a man’s voice shouting frantically, “Help, help! Miss Maybourne

has fallen overboard.”

The words were scarcely out of his mouth before I had left the

alley way, crossed the well, and was climbing the ladder that led to

the poop. A second or two later I was at the taffrail, had thrown off

my coat, mounted the rail, and, catching sight of a figure struggling

among the cream of the wake astern, had plunged in after her. The

whole thing, from the time the first shriek was uttered until I had

risen to the surface, and was blowing the water from my mouth and

looking about me for the girl, could not have taken more than twenty

seconds, and yet in it I seemed to live a lifetime. Ahead of me the

great ship towered up to the heavens; all round me was the black

bosom of the ocean, with the stars looking down at it in their

winking grandeur.

For some moments after I had come to the surface I could see

nothing of the girl I had jumped overboard to |rescue. She seemed to

have quite disappeared. Then, while on the summit of a wave, I caught

a glimpse of her, and, putting forth all my strength, swam towards

her. Eternities elapsed before I reached her. When I did I came

carefully up alongside, and put my left arm under her shoulders to

sustain her. She was quite sensible, and, strangely enough, not in

the least frightened.

“Can you swim?” I asked, anxiously, as I began to tread water.

“A little, but not very well,” she answered. “I’m afraid I am

getting rather tired.”

“Lean upon me,” I answered. “Try not to be afraid; they will lower

a boat in a few moments, and pick us up.”

She said no more, but fought hard to keep herself afloat. The

weight upon my arm was almost more than I could bear, and I began to

fear that if the rescue boat did not soon pick us up they might have

their row for nothing. Then my ears caught the chirp of oars, and the

voice of the second officer encouraging his men in their search for

us.

“If you can hold on for another three or four minutes,” I said in

gasps to my companion, “all will be well.”

“I will try,” she answered, bravely; “but I fear I shall not be

able to. My strength is quite gone.”

Her clothes were sodden with water, and added greatly to the

weight I had to support. Not once, but half-a-dozen times, seas,

cold as ice, broke over us; and once I was compelled to let go my

hold of her. When I rose to the surface again some seconds elapsed

before I could find her. She had sunk, and by the time I had dived

and got my arm round her again she was quite unconscious. The boat

was now about thirty yards distant from us, and already the men in

her had sighted us and were pulling with all their strength to our

assistance. In another minute or so they would be alongside, but the

question was whether I could hold out so long. A minute contained

sixty seconds, and each second was an eternity of waiting.

When they were near enough to hear my voice I called to them with

all my strength to make haste. I saw the bows of the boat come closer

and closer, and could distinctly distinguish the hissing of the water

under her bows.

“If you can hold on for a few seconds longer,” shouted the officer

in command, “we’ll get you aboard.”

I heard the men on the starboard side throw in their oars.

Comments (0)