Blind Love, Wilkie Collins [ebook reader 8 inch TXT] 📗

- Author: Wilkie Collins

- Performer: -

Book online «Blind Love, Wilkie Collins [ebook reader 8 inch TXT] 📗». Author Wilkie Collins

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Blind Love, by Wilkie Collins #30 in our series by Wilkie Collins

Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook.

This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission.

Please read the “legal small print,” and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved.

**Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts**

**eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971**

*****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!*****

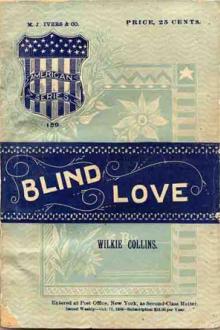

Title: Blind Love

Author: Wilkie Collins

Release Date: April, 2005 [EBook #7890] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on May 31, 2003]

Edition: 10

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BLIND LOVE ***

Produced by James Rusk

Blind Love

by Wilkie Collins (completed by Walter Besant)

PREFACE

IN the month of August 1889, and in the middle of the seaside holiday, a message came to me from Wilkie Collins, then, though we hoped otherwise, on his deathbed.

It was conveyed to me by Mr. A. P. Watt. He told me that his son had just come from Wilkie Collins: that they had been speaking of his novel, “Blind Love,” then running in the Illustrated London News: that the novel was, unfortunately, unfinished: that he himself could not possibly finish it: and that he would be very glad, if I would finish it if I could find the time. And that if I could undertake this work he would send me his notes of the remainder. Wilkie Collins added these words: “If he has the time I think he will do it: we are both old hands at this work, and understand it, and he knows that I would do the same for him if he were in my place.”

Under the circumstances of the case, it was impossible to decline this request. I wrote to say that time should be made, and the notes were forwarded to me at Robin Hood’s Bay. I began by reading carefully and twice over, so as to get a grip of the story and the novelist’s intention, the part that had already appeared, and the proofs so far as the author had gone. I then turned to the notes. I found that these were not merely notes such as I expected—simple indications of the plot and the development of events, but an actual detailed scenario, in which every incident, however trivial, was carefully laid down: there were also fragments of dialogue inserted at those places where dialogue was wanted to emphasise the situation and make it real. I was much struck with the writer’s perception of the vast importance of dialogue in making the reader seize the scene. Description requires attention: dialogue rivets attention.

It is not an easy task, nor is it pleasant, to carry on another man’s work: but the possession of this scenario lightened the work enormously. I have been careful to adhere faithfully and exactly to the plot, scene by scene, down to the smallest detail as it was laid down by the author in this book. I have altered nothing. I have preserved and incorporated every fragment of dialogue. I have used the very language wherever that was written so carefully as to show that it was meant to be used. I think that there is only one trivial detail where I had to choose because it was not clear from the notes what the author had intended. The plot of the novel, every scene, every situation, from beginning to end, is the work of Wilkie Collins. The actual writing is entirely his up to a certain point: from that point to the end it is partly his, but mainly mine. Where his writing ends and mine begins, I need not point out. The practised critic will, no doubt, at once lay his finger on the spot.

I have therefore carried out the author’s wishes to the best of my ability. I would that he were living still, if only to regret that he had not been allowed to finish his last work with his own hand!

WALTER BESANT.

BLIND LOVE

THE PROLOGUE

I

SOON after sunrise, on a cloudy morning in the year 1881, a special messenger disturbed the repose of Dennis Howmore, at his place of residence in the pleasant Irish town of Ardoon.

Well acquainted apparently with the way upstairs, the man thumped on a bedroom door, and shouted his message through it: “The master wants you, and mind you don’t keep him waiting.”

The person sending this peremptory message was Sir Giles Mountjoy of Ardoon, knight and banker. The person receiving the message was Sir Giles’s head clerk. As a matter of course, Dennis Howmore dressed himself at full speed, and hastened to his employer’s private house on the outskirts of the town.

He found Sir Giles in an irritable and anxious state of mind. A letter lay open on the banker’s bed, his night-cap was crumpled crookedly on his head, he was in too great a hurry to remember the claims of politeness, when the clerk said “Good morning.”

“Dennis, I have got something for you to do. It must be kept a secret, and it allows of no delay.”

“Is it anything connected with business, sir?”

The banker lost his temper. “How can you be such an infernal fool as to suppose that anything connected with business could happen at this time in the morning? Do you know the first milestone on the road to Garvan?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Very well. Go to the milestone, and take care that nobody sees you when you get there. Look at the back of the stone. If you discover an Object which appears to have been left in that situation on the ground, bring it to me; and don’t forget that the most impatient man in all Ireland is waiting for you.”

Not a word of explanation followed these extraordinary instructions.

The head clerk set forth on his errand, with his mind dwelling on the national tendencies to conspiracy and assassination. His employer was not a popular person. Sir Giles had paid rent when he owed it; and, worse still, was disposed to remember in a friendly spirit what England had done for Ireland, in the course of the last fifty years. If anything appeared to justify distrust of the mysterious Object of which he was in search, Dennis resolved to be vigilantly on the look-out for a gun-barrel, whenever he passed a hedge on his return journey to the town.

Arrived at the milestone, he discovered on the ground behind it one Object only—a fragment of a broken tea-cup.

Naturally enough, Dennis hesitated. It seemed to be impossible that the earnest and careful instructions which he had received could relate to such a trifle as this. At the same time, he was acting under orders which were as positive as tone, manner, and language could make them. Passive obedience appeared to be the one safe course to take—at the risk of a reception, irritating to any man’s self-respect, when he returned to his employer with a broken teacup in his hand.

The event entirely failed to justify his misgivings. There could be no doubt that Sir Giles attached serious importance to the contemptible discovery made at the milestone. After having examined and re-examined the fragment, he announced his intention of sending the clerk on a second errand—still without troubling himself to explain what his incomprehensible instructions meant.

“If I am not mistaken,” he began, “the Reading Rooms, in our town, open as early as nine. Very well. Go to the Rooms this morning, on the stroke of the clock.” He stopped, and consulted the letter which lay open on his bed. “Ask the librarian,” he continued, “for the third volume of Gibbon’s ‘Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.’ Open the book at pages seventy-eight and seventy-nine. If you find a piece of paper between those two leaves, take possession of it when nobody is looking at you, and bring it to me. That’s all, Dennis. And bear in mind that I shall not recover the use of my patience till I see you again.”

On ordinary occasions, the head clerk was not a man accustomed to insist on what was due to his dignity. At the same time he was a sensible human being, conscious of the consideration to which his responsible place in the office entitled him. Sir Giles’s irritating reserve, not even excused by a word of apology, reached the limits of his endurance. He respectfully protested.

“I regret to find, sir,” he said, “that I have lost my place in my employer’s estimation. The man to whom you confide the superintendence of your clerks and the transaction of your business has, I venture to think, some claim (under the present circumstances) to be trusted.”

The banker was now offended on his side.

“I readily admit your claim,” he answered, “when you are sitting at your desk in my office. But, even in these days of strikes, co-operations, and bank holidays, an employer has one privilege left—he has not ceased to be a Man, and he has not forfeited a man’s right to keep his own secrets. I fail to see anything in my conduct which has given you just reason to complain.”

Dennis, rebuked, made his bow in silence, and withdrew.

Did these acts of humility mean that he submitted? They meant exactly the contrary. He had made up his mind that Sir Giles Mountjoy’s motives should, sooner or later, cease to be mysteries to Sir Giles Mountjoy’s clerk.

II

CAREFULLY following his instructions, he consulted the third volume of Gibbon’s great History, and found, between the seventy-eighth and seventy-ninth pages, something remarkable this time.

It was a sheet of delicately-made paper, pierced with a number of little holes, infinitely varied in size, and cut with the smoothest precision. Having secured this curious object, while the librarian’s back was turned, Dennis Howmore reflected.

A page of paper, unintelligibly perforated for some purpose unknown, was in itself a suspicious thing. And what did suspicion suggest to the inquiring mind in South-Western Ireland, before the suppression of the Land League? Unquestionably–Police!

On the way back to his employer, the banker’s clerk paid a visit to an old friend—a journalist by profession, and a man of varied learning and experience as well. Invited to inspect the remarkable morsel of paper, and to discover the object with which the perforations had been made, the authority consulted proved to be worthy of the trust reposed in him. Dennis left the newspaper office an enlightened man—with information at the disposal of Sir Giles, and with a sense of relief which expressed itself irreverently in these words: “Now I have got him!”

The bewildered banker looked backwards and forwards from the paper to the clerk, and from the clerk to the paper. “I don’t understand it,” he said. “Do you?”

Still preserving the

Comments (0)