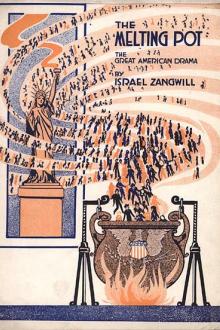

The Melting-Pot, Israel Zangwill [inspirational books to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: Israel Zangwill

- Performer: -

Book online «The Melting-Pot, Israel Zangwill [inspirational books to read .TXT] 📗». Author Israel Zangwill

When the Vigilantes took their stations, the scene was like a battlefield. Bullets were flying from both sides of the Red Cross carriages. We expected to be killed any minute, but notwithstanding, we rushed wherever there were shots heard in order to carry away the wounded. Whenever we arrived we shouted "Red Cross, Red Cross," in order to help make them realise we were not Vigilantes. Then they would stop and let us pick up the wounded. They did this on account of their own wounded.

The Vigilantes could not stop the butchery entirely because they were not strong enough in numbers. On the fourth day, the Jewish people of Odessa, through Dr. P——, succeeded in communicating to the Mayor of a different State. Soldiers from outside, strangers to the murderers, came in and took charge of the city. The city was put under martial law until order could be restored.

On the fifth day the doctors and nurses were called to the cemetery, where there were four hundred unidentified dead. Their friends and relatives who came to search for them were crazed and hysterical and needed our attention. Wives came to look for husbands, parents hunting children, a mother for her only son, and so on. It took eight days to identify the bodies and by that time four hundred of the wounded had died, and so we had eight hundred to bury. If you visit Odessa, you will be shown two long graves, about one hundred feet long, beside the Jewish Cemetery. There lie the victims of the massacre. Among them are Gentile Vigilantes whose parents asked that they be buried with the Jews....

Another case I knew was that of a married man. He left his wife, who was pregnant, and three children, to go on a business trip. When he got back the massacre had occurred. His home was in ruins, his family gone. He went to the hospital, then to the cemetery. There he found his wife with her abdomen stuffed with straw, and his three children dead. It simply broke his heart, and he lost his mind. But he was harmless, and was to be seen wandering about the hospital as though in search of some one, and daily he grew more thin and suffering.

This story is told in the hope that Americans will appreciate the safety and freedom in which they live and that they will help others to gain that freedom.

APPENDIX C THE STORY OF DANIEL MELSAAnother example of Nature aping Art is afforded by the romantic story of Daniel Melsa, a young Russo-Jewish violinist who has carried audiences by storm in Berlin, Paris and London, and who had arranged to go to America last November. The following extract from an interview in the Jewish Chronicle of January 24, 1913, shows the curious coincidence between his beginnings and David Quixano's:

"Melsa is not yet twenty years of age, but he looks somewhat older. He is of slight build and has a sad expression, which increased to almost a painful degree when recounting some of his past experiences. He seems singularly devoid of any affectation, while modesty is obviously the keynote of his nature.

"After some persuasion, Melsa put aside his reticence, and, complying with the request, outlined briefly his career, the early part of which, he said, was overshadowed by a great tragedy. He was born in Warsaw, and, at the age of three, his parents moved to Lodz, where shortly after a private tutor was engaged for him.

"'Although I exhibited a passion for music quite early, I did not receive any lessons on the subject till my seventh birthday, but before that my father obtained a cheap violin for me upon which I was soon able to play simple melodies by ear.'

"By chance a well-known professor of the town heard him play, and so impressed was he with the talent exhibited by the boy that he advised the father to have him educated. Acting upon this advice, as far as limited means allowed, tutors were engaged, and so much progress did he make that at the age of nine he was admitted to the local Conservatorium of Professor Grudzinski, where he remained two years. It was at the age of eleven that a great calamity overtook the family, his father and sister falling victims to the pogroms.

"Melsa's story runs as follows:

"'It was in June of 1905, at the time of the pogroms, when one afternoon my father, accompanied by my little sister, ventured out into the street, from which they never returned. They were both killed,' he added sadly, 'by Cossacks. A week later I found my sister in a Christian churchyard riddled with bullets, but I have not been able to trace the remains of my father, who must have been buried in some out-of-the-way place. During this awful period my mother and myself lived in imminent danger of our lives, and it was only the recollection of my playing that saved us also falling a prey to the vodka-besodden Cossacks.'"

APPENDIX D BEILIS AND AMERICAThe close relation in Jewish thought between Russo-Jewish persecution and America as the land of escape from it is well illustrated by the recent remarks of the Jewish Chronicle on the future of the victim of the Blood-Ritual Prosecution in Kieff. "So long as Beilis continues to live in Russia, his life is unsafe. The Black Hundreds, he himself says, have solemnly decided on his death, and we have seen, in the not distant past, that they can carry out diabolical plots of this description with complete immunity.... He would gladly go to America, provided he was sure of a living. The condition should not be difficult to fulfil, and if this victim of a barbarous régime—we cannot say latest victim, for, as we write, comes the news of an expulsion order against 1200 Jewish students of Kieff—should find a home and place under the sheltering wing of freedom, it would be a fitting ending to a painful chapter in our Jewish history."

That it is the natural ending even the Jew-baiting Russian organ, the Novoe Vremya, indirectly testifies, for it has published a sneering cartoon representing a number of Jews crowded on the Statue of Liberty to welcome the arrival of Beilis. One wonders that the Russian censor should have permitted the masses to become aware that Liberty exists on earth, if only in the form of a statue.

APPENDIX E THE ALIEN IN THE MELTING POTMr. Frederick J. Haskin has recently published in the Chicago Daily News the following graphic summary of what immigrants have done and do for the United States:

I am the immigrant.

Since the dawn of creation my restless feet have beaten new paths across the earth.

My uneasy bark has tossed on all seas.

My wanderlust was born of the craving for more liberty and a better wage for the sweat of my face.

I looked towards the United States with eyes kindled by the fire of ambition and heart quickened with new-born hope.

I approached its gates with great expectation.

I entered in with fine hopes.

I have shouldered my burden as the American man of all work.

I contribute eighty-five per cent. of all the labour in the slaughtering and meat-packing industries.

I do seven-tenths of the bituminous coal mining.

I do seventy-eight per cent. of all the work in the woollen mills.

I contribute nine-tenths of all the labour in the cotton mills.

I make nine-twentieths of all the clothing.

I manufacture more than half the shoes.

I build four-fifths of all the furniture.

I make half of the collars, cuffs, and shirts.

I turn out four-fifths of all the leather.

I make half the gloves.

I refine nearly nineteen-twentieths of the sugar.

I make half of the tobacco and cigars.

And yet, I am the great American problem.

When I pour out my blood on your altar of labour, and lay down my life as a sacrifice to your god of toil, men make no more comment than at the fall of a sparrow.

But my brawn is woven into the warp and woof of the fabric of your national being.

My children shall be your children and your land shall be my land because my sweat and my blood will cement the foundations of the America of To-Morrow.

If I can be fused into the body politic, the Melting-Pot will have stood the supreme test.

Afterword IThe Melting Pot is the third of the writer's plays to be published in book form, though the first of the three in order of composition. But unlike The War God and The Next Religion, which are dramatisations of the spiritual duels of our time, The Melting Pot sprang directly from the author's concrete experience as President of the Emigration Regulation Department of the Jewish Territorial Organisation, which, founded shortly after the great massacres of Jews in Russia, will soon have fostered the settlement of ten thousand Russian Jews in the West of the United States.

"Romantic claptrap," wrote Mr. A. B. Walkley in the Times of "this rhapsodising over music and crucibles and statues of Liberty." As if these things were not the homeliest of realities, and rhapsodising the natural response to them of the Russo-Jewish psychology, incurably optimist. The statue of Liberty is a large visible object at the mouth of New York harbour; the crucible, if visible only to the eye of imagination like the inner reality of the sunrise to the eye of Blake, is none the less a roaring and flaming actuality. These things are as substantial, if not as important, as Adeline Genée and Anna Pavlova, the objects of Mr. Walkley's own rhapsodising. Mr. Walkley, never having lacked Liberty, nor cowered for days in a cellar in terror of a howling mob, can see only theatrical exaggeration in the enthusiasm for a land of freedom, just as, never having known or never having had eyes to see the grotesque and tragic creatures existing all around us, he has doubted the reality of some of Balzac's creations. It is to be feared that for such a play as The Melting Pot Mr. Walkley is far from being the χαρίεις of Aristotle. The ideal spectator must have known and felt more of life than Mr. Walkley, who resembles too much the library-fed man of letters whose denunciation by Walter Bagehot he himself quotes without suspecting de te fabula narratur. Even the critic, who has to deal with a refracted world, cannot dispense with primary experience of his own. For "the adventures of a soul among masterpieces" it is not only necessary there should be masterpieces, there must also be a soul. Mr. Walkley, one of the wittiest of contemporary writers and within his urban range one of the wisest, can scarcely be accused of lacking a soul, though Mr. Bernard Shaw's long-enduring misconception of him as a brother in the spirit is one of the comedies of literature. But such spiritual vitality as Oxford failed to sterilise in him has been largely torpified by his profession of play-taster, with its divorcement from reality in the raw. His cry of "romantic claptrap" is merely the reaction of the club armchair to the

Comments (0)