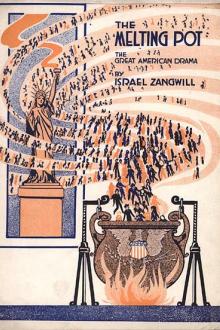

The Melting-Pot, Israel Zangwill [inspirational books to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: Israel Zangwill

- Performer: -

Book online «The Melting-Pot, Israel Zangwill [inspirational books to read .TXT] 📗». Author Israel Zangwill

Mr. Roosevelt, with his multifarious American experience as soldier and cowboy, hunter and historian, police-captain and President, comes far nearer the ideal spectator, for this play at least, than Mr. Walkley. Yet his enthusiasm for it has been dismissed by our critic as "stupendous naïveté." Mr. Roosevelt apparently falls under that class of "people who knowing no rules, are at the mercy of their undisciplined taste," which Mr. Walkley excludes altogether from his classification of critics, in despite of Dr. Johnson's opinion that "natural judges" are only second to "those who know but are above the rules." It is comforting, therefore, to find Mr. Augustus Thomas, the famous American playwright, who is familiar with the rules to the point of contempt, chivalrously associating himself, in defence of a British rival, with Mr. Roosevelt's "stupendous naïveté."

"Mr. Zangwill's 'rhapsodising' over music and crucibles and statues of Liberty is," says Mr. Thomas, "a very effective use of a most potent symbolism, and I have never seen men and women more sincerely stirred than the audience at The Melting Pot. The impulses awakened by the Zangwill play were those of wide human sympathy, charity, and compassion; and, for my own part, I would rather retire from the theatre and retire from all direct or indirect association with journalism than write down the employment of these factors by Mr. Zangwill as mere claptrap."

"As a work of art for art's sake," also wrote Mr. William Archer, "the play simply does not exist." He added: "but Mr. Zangwill would not dream of appealing to such a standard." Mr. Archer had the misfortune to see the play in New York side by side with his more cynical confrère, and thus his very praise has an air of apologia to Mr. Walkley and the great doctrine of "art for art's sake." It would almost seem as if he even takes a "work of art" and a "work of art for art's sake" as synonymous. Nothing, in fact, could be more inartistic. "Art for art's sake" is one species of art, whose right to existence the author has amply recognised in other works. (The King of Schnorrers was even read aloud by Oscar Wilde to a duchess.) But he roundly denies that art is any the less artistic for being inspired by life, and seeking in its turn to inspire life. Such a contention is tainted by the very Philistinism it would repudiate, since it seeks a negative test of art in something outside art—to wit, purpose, whose presence is surely as irrelevant to art as its absence. The only test of art is artistic quality, and this quality occurs perhaps more frequently than it is achieved, as in the words of the Hebrew prophets, or the vision of a slum at night, the former consciously aiming at something quite different, the latter achieving its beauty in utter unconsciousness.

IIIt will be seen from the official table of immigration that the Russian Jew is only one and not even the largest of the fifty elements that, to the tune of nearly a million and a half a year, are being fused in the greatest "Melting Pot" the world has ever known; but if he has been selected as the typical immigrant, it is because he alone of all the fifty has no homeland. Some few other races, such as the Armenians, are almost equally devoid of political power, and, in consequence, equally obnoxious to massacre; but except the gipsy, whose essence is to be homeless, there is no other race—black, white, red, or yellow—that has not remained at least a majority of the population in some area of its own. There is none, therefore, more in need of a land of liberty, none to whose future it is more vital that America should preserve that spirit of William Penn which President Wilson has so nobly characterised. And there is assuredly none which has more valuable elements to contribute to the ethnic and psychical amalgam of the people of to-morrow.

The process of American amalgamation is not assimilation or simple surrender to the dominant type, as is popularly supposed, but an all-round give-and-take by which the final type may be enriched or impoverished. Thus the intelligent reader will have remarked how the somewhat anti-Semitic Irish servant of the first act talks Yiddish herself in the fourth. Even as to the ultimate language of the United States, it is unreasonable to suppose that American, though fortunately protected by English literature, will not bear traces of the fifty languages now being spoken side by side with it, and of which this play alone presents scraps in German, French, Russian, Yiddish, Irish, Hebrew, and Italian.

That in the crucible of love, or even co-citizenship, the most violent antitheses of the past may be fused into a higher unity is a truth of both ethics and observation, and it was in order to present historic enmities at their extremes that the persecuted Jew of Russia and the persecuting Russian race have been taken for protagonists—"the fell incensèd points of mighty opposites."

The Jewish immigrant is, moreover, the toughest of all the white elements that have been poured into the American crucible, the race having, by its unique experience of several thousand years of exposure to alien majorities, developed a salamandrine power of survival. And this asbestoid fibre is made even more fireproof by the anti-Semitism of American uncivilisation. Nevertheless, to suppose that America will remain permanently afflicted by all the old European diseases would be to despair of humanity, not to mention super-humanity.

IIIEven the negrophobia is not likely to remain eternally at its present barbarous pitch. Mr. William Archer, who has won a new fame as student of that black problem, which is America's nemesis for her ancient slave-raiding, and who favours the creation of a Black State as one of the United States, observes: "It is noteworthy that neither David Quixano nor anyone else in the play makes the slightest reference to that inconvenient element in the crucible of God—the negro." This is an oversight of Mr. Archer's, for Baron Revendal defends the Jew-baiting of Russia by asking of an American: "Don't you lynch and roast your niggers?" And David Quixano expressly throws both "black and yellow" into the crucible. No doubt there is an instinctive antipathy which tends to keep the white man free from black blood, though this antipathy having been overcome by a large minority in all the many periods and all the many countries of their contiguity, it is equally certain that there are at work forces of attraction as well as of repulsion, and that even upon the negro the "Melting Pot" of America will not fail to act in a measure as it has acted on the Red Indian, who has found it almost as facile to mate with his white neighbours as with his black. Indeed, it is as much social prejudice as racial antipathy that to-day divides black and white in the New World; and Sir Sydney Olivier has recorded that in Jamaica the white is far more on his guard and his dignity against the half-white than against the all-black, while in Guiana, according to Sir Harry Johnston in his great work "The Negro in the New World," it is the half-white that, in his turn, despises the black and succeeds in marrying still further whitewards. It might have been thought that the dark-white races on the northern shore of the Mediterranean—the Spaniards, Sicilians, &c.—who have already been crossed with the sons of Ham from its southern shore, would, among the American immigrants, be the natural links towards the fusion of white and black, but a similar instinct of pride and peril seems to hold them back. But whether the antipathy in America be a race instinct or a social prejudice, the accusations against the black are largely panic-born myths, for the alleged repulsive smell of the negro is consistent with being shaved by him, and the immorality of the negress is consistent with her control of the nurseries of the South. The devil is not so black nor the black so devilish as he is painted. This is not to deny that the prognathous face is an ugly and undesirable type of countenance or that it connotes a lower average of intellect and ethics, or that white and black are as yet too far apart for profitable fusion. Melanophobia, or fear of the black, may be pragmatically as valuable a racial defence for the white as the counter-instinct of philoleucosis, or love of the white, is a force of racial uplifting for the black. But neither colour has succeeded in monopolising all the virtues and graces in its specific evolution from the common ancestral ape, and a superficial acquaintance with the work of Dr. Arthur Keith teaches that if the black man is nearer the ape in some ways (having even the remains of throat-pouches), the white man is nearer in other ways (as in his greater hairiness).

And besides being, as Sir Sydney Olivier says, "a matrix of emotional and spiritual energies that have yet to find their human expression," the African negro has obviously already not a few valuable ethnic elements—joy of life, love of colour, keen senses, beautiful voice, and ear for music—contributions that might somewhat compensate for the dragging-down of the white and, in small doses at least, might one day prove a tonic to an anæmic and art-less America. A musician like Coleridge-Taylor is no despicable product of the "Melting Pot," while the negroes of genius whom the writer has been privileged to know—men like Henry O. Tanner, the painter, and Paul Laurence Dunbar, the poet—show the potentialities of the race even without white admixture; and as men of this stamp are capable of attracting cultured white wives, the fusing process, beginning at the top with types like these, should be far less unwelcome than that which starts with the dregs of both races. But the negroid hair and complexion being, in Mendelian language, "dominant," these black traits are not easy to eliminate from the hybrid posterity; and in view of all the unpleasantness, both immediate and contingent, that attends the blending of colours, only heroic souls on either side should dare the adventure of intermarriage. Blacks of this temper, however, would serve their race better by making Liberia a success or building up an American negro State, as Mr. William Archer recommends, or at least asserting their rights as American citizens in that sub-tropical South which without their labour could never have been opened up. Meantime, however scrupulously and justifiably America avoids physical intermarriage with the negro, the comic spirit cannot fail to note the spiritual miscegenation which, while clothing, commercialising, and Christianising the ex-African, has given "rag-time" and the sex-dances that go to it, first to white America and thence to the whole white world.

The action of the crucible is thus not exclusively physical—a consideration particularly important as regards the Jew. The Jew may be Americanised and the American Judaised without any gamic interaction.

IVAmong the Jews The Melting Pot, though it has in some instances served to interpret to each other the old generation and the new, has more frequently been misunderstood by both. While a distinguished Christian clergyman wrote that it was "calculated to do for the

Comments (0)