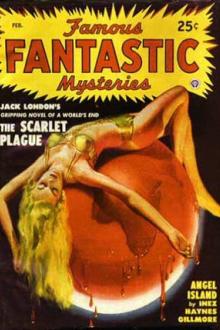

Angel Island, Inez Haynes Gillmore [the two towers ebook txt] 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island, Inez Haynes Gillmore [the two towers ebook txt] 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

white sand; and there seemed something calculating about that - as

though she were bribing them with jewels to forget.

“Say, let’s cut out this business of going, over and over it,” said

Ralph Addington with a sudden burst of irritability. “I guess I could

give up the ship’s cat in exchange for a girl or two.” Addington’s face

was livid; a muscular contraction kept pulling his lips away from his

white teeth; he had the look of a man who grins satanically at regular

intervals.

By a titanic mental effort, the others connected this explosion with

Billy Fairfax’s last remark. It was the first expression of an emotion

so small as ill-humor. It was, moreover, the first excursion out of the

beaten path of their egotisms. It cleared the atmosphere a little of

that murky cloud of horror which blurred the sunlight. Three of the

other four men - Honey Smith, Frank Merrill, Pete Murphy - actually

turned and looked at Ralph Addington. Perhaps that movement served to

break the hideous, hypnotic spell of the sea.

“Right-o!” Honey Smith agreed weakly. It was audible in his voice, the

effort to talk sanely of sane things, and in the slang of every day.

“Addington’s on. Let’s can it! Here we are and here we’re likely to stay

for a few days. In the meantime we’ve got to live. How are we going to

pull it off?”

Everybody considered his brief harangue; for an instant, it looked as

though this consideration was taking them all back into aimless

meditation. Then, “That’s right,” Billy Fairfax took it up heroically.

“Say, Merrill,” he added in almost a conversational tone, “what are our

chances? I mean how soon do we get off?”

This was the first question anybody had asked. It added its

infinitesimal weight to the wave of normality which was settling over

them all. Everybody visibly concentrated, listening for the answer.

It came after an instant, although Frank Merrill palpably pulled himself

together to attack the problem. “I was talking that matter over with

Miner just yesterday,” he said. “Miner said God, I wonder where he is

now - and a dependent blind mother in Nebraska.”

“Cut that out,” Honey Smith ordered crisply.

“We - we - were trying to figure our chances in case of a wreck,” Frank

Merrill continued slowly. “You see, we’re out of the beaten path - way

out. Those days of drifting cooked our goose. You can never tell, of

course, what will happen in the Pacific where there are so many tramp

craft. On the other hand - ” he paused and hesitated. It was evident,

now that he had something to expound, that Merrill had himself almost

under command, that his hesitation arose from another cause. “Well,

we’re all men. I guess it’s up to me to tell you the truth. The sooner

you all know the worst, the sooner you’ll pull yourselves together. I

shouldn’t be surprised if we didn’t see a ship for several weeks -

perhaps months.”

Another of their mute intervals fell upon them. Dozens of waves flashed

and crashed their way up the beach; but now they trailed an iridescent

network of foam over the lilac-gray sand. The sun raced high; but now it

poured a flood of light on the green-gray water. The air grew bright and

brighter. The earth grew warm and warmer. Blue came into the sky,

deepened - and the sea reflected it, Suddenly the world was one huge

glittering bubble, half of which was the brilliant azure sky and half

the burnished azure sea. None of the five men looked at the sea and sky

now. The other four were considering Frank Merrill’s words and he was

considering the other four.

“Lord, God!” Ralph Addington exclaimed suddenly. “Think of being in a

place like this six months or a year without a woman round! Why, we’ll

be savages at the end of three months.” He snarled his words. It was as

if a new aspect of the situation - an aspect more crucially alarming

than any other - had just struck him.

“Yes,” said Frank Merrill. And for a moment, so much had he recovered

himself, he reverted to his academic type. “Aside from the regret and

horror and shame that I feel to have survived when every woman drowned,

I confess to that feeling too. Women keep up the standards of life. It

would have made a great difference with us if there were only one or two

women here.”

“If there’d been five, you mean,” Ralph Addington amended. A feeble,

white-toothed smile gleamed out of his dark beard. He, too, had pulled

himself together; this smile was not muscular contraction. “One or two,

and the fat would be in the fire.”

Nobody added anything to this. But now the other three considered Ralph

Addington’s words with the same effort towards concentration that they

had brought to Frank Merrill’s. Somehow his smile - that flashing smile

which showed so many teeth against a background of dark beard - pointed

his words uncomfortably.

Of them all, Ralph Addington was perhaps, the least popular. This was

strange; for he was a thorough sport, a man of a wide experience. He was

salesman for a business concern that manufactured a white shoe-polish,

and he made the rounds of the Oriental countries every year. He was a

careful and intelligent observer both of men and things. He was widely

if not deeply read. He was an interesting talker. He could, for or

instance, meet each of the other four on some point of mental contact. A

superficial knowledge of sociology and a practical experience with many

races brought him and Frank Merrill into frequent discussion. His

interest in all athletic sports and his firsthand information in regard

to them made common ground between him and Billy Fairfax. With Honey

Smith, he talked business, adventure, and romance; with Pete Murphy,

German opera, French literature, American muckraking, and Japanese art.

The flaw which made him alien was not of personality but of character.

He presented the anomaly of a man scrupulously honorable in regard to

his own sex, and absolutely codeless in regard to the other. He was what

modern nomenclature calls a “contemporaneous varietist.” He was, in

brief, an offensive type of libertine. Woman, first and foremost, was

his game. Every woman attracted him. No woman held him. Any new woman,

however plain, immediately eclipsed her predecessor, however beautiful.

The fact that amorous interests took precedence over all others was

quite enough to make him vaguely unpopular with men. But as in addition,

he was a physical type which many women find interesting, it is likely

that an instinctive sex-jealousy, unformulated but inevitable, biassed

their judgment. He was a typical business man; but in appearance he

represented the conventional idea of an artist. Tall, muscular,

graceful, hair thick and a little wavy, beard pointed and golden-brown,

eyes liquid and long-lashed, women called him “interesting.” There was,

moreover, always a slight touch of the picturesque in his clothes; he

was master of the small amatory ruses which delight flirtatious women.

In brief, men were always divided in their own minds in regard to Ralph

Addington. They knew that, constantly, he broke every canon of that

mysterious flexible, half-developed code which governs their relations

with women. But no law of that code compelled them to punish him for

ungenerous treatment of somebody’s else wife or sister. Had he been

dishonorable with them, had he once borrowed without paying, had he once

cheated at cards, they would have ostracized him forever. He had done

none of these things, of course.

“By jiminy!” exclaimed Honey Smith, “how I hate the unfamiliar air of

everything. I’d like to put my lamps on something I know. A ranch and a

round-up would look pretty good to me at this moment. Or a New England

farmhouse with the cows coming home. That would set me up quicker than a

highball.”

“The University campus would seem like heaven to me,” Frank Merrill

confessed drearily, “and I’d got so the very sight of it nearly drove me

insane.”

“The Great White Way for mine,” said Pete Murphy, “at night - all the

corset and whisky signs flashing, the streets jammed with

benzine-buggies, the sidewalks crowded with boobs, and every lobster

palace filled to the roof with chorus girls.”

“Say,” Billy Fairfax burst out suddenly; and for the first time since

the shipwreck a voice among them carried a clear business-like note of

curiosity. “You fellows troubled with your eyes? As sure as shooting,

I’m seeing things. Out in the west there - black spots - any of the rest

of you get them?”

One or two of the group glanced cursorily backwards. A pair of

perfunctory “Noes!” greeted Billy’s inquiry.

“Well, I’m daffy then,” Billy decided. He went on with a sudden abnormal

volubility. “Queer thing about it is I’ve been seeing them the whole

morning. I’ve just got back to that Point where I realized there was

something wrong. I’ve always had a remarkably far sight.” He rushed on

at the same speed; but now he had the air of one who is trying to

reconcile puzzling phenomena with natural laws. “And it seems as if -

but there are no birds large enough - wish it would stop, though.

Perhaps you get a different angle of vision down in these parts. Did any

of you ever hear of that Russian peasant who could see the four moons of

Jupiter without a glass? The astronomers tell about him.”

Nobody answered his question. But it seemed suddenly to bring them back

to the normal.

“See here, boys,” Frank Merrill said, an unexpected note of authority in

his voice, “we can’t sit here all the morning like this. We ought to rig

up a signal, in case any ship -. Moreover, we’ve got to get together and

save as much as we can. We’ll be hungry in a little while. We can’t lie

down on that job too long.”

Honey Smith jumped to his feet. “Well, Lord knows, I want to get busy. I

don’t want to do any more thinking, thank you. How I ache! Every muscle

in my body is raising particular Hades at this moment.”

The others pulled themselves up, groaned, stretched, eased protesting

muscles. Suddenly Honey Smith pounded Billy Fairfax on the shoulder,

“You’re it, Billy,” he said and ran down the beach. In another instant

they were all playing tag. This changed after five minutes to baseball

with a lemon for a ball and a chair-leg for a bat. A mood of wild

exhilaration caught them. The inevitable psychological reaction had set

in. Their morbid horror of Nature vanished in its vitalizing flood like

a cobweb in a flame. Never had sea or sky or earth seemed more lovely,

more lusciously, voluptuously lovely. The sparkle of the salt wind

tingled through their bodies like an electric current. The warmth in the

air lapped them like a hot bath. Joy-in-life flared up in them to such a

height that it kept them running and leaping meaninglessly. They shouted

wild phrases to each other. They burst into song. At times they yelled

scraps of verse.

“We’ll come across something to eat soon,” said Frank Merrill, breathing

hard. “Then we’ll be all right.”

“I feel - better - for that run - already,” panted Billy Fairfax.

“Haven’t seen a black spot for five minutes.”

Nobody paid any attention to him, and in a few minutes he was paying no

attention to himself. Their expedition was offering too many shocks of

horror and pathos. Fortunately the change in their mood held. It was,

indeed, as unnatural as their torpor, and must inevitably bring its own

reaction. But after

Comments (0)