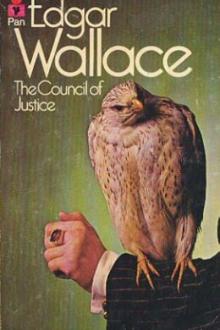

The Council of Justice, Edgar Wallace [english novels to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Council of Justice, Edgar Wallace [english novels to read .txt] 📗». Author Edgar Wallace

fired the shots.

In an instant the place was a pandemonium.

‘Silence!’ Falmouth roared above the din; ‘silence! Keep quiet, you

miserable cowards—show a light here, Brown, Curtis—Inspector, where

are your men’s lanterns!’

The rays of a dozen bull’s-eye lamps waved over the struggling

throng.

‘Open your lanterns’—and to the seething mob, ‘Silence!’ Then a

bright young officer remembered that he had seen gas-brackets in the

room, and struggled through the howling mob till he came to the wall

and found the gas-fitting with his lantern. He struck a match and lit

the gas, and the panic subsided as suddenly as it had begun.

Falmouth, choked with rage, threw his eye round the hall. ‘Guard the

door,’ he said briefly; ‘the hall is surrounded and they cannot

possibly escape.’ He strode swiftly along the central aisle, followed

by two of his men, and with an agile leap, sprang on to the platform

and faced the audience. The Woman of Gratz, with a white set face,

stood motionless, one hand resting on the little table, the other at

her throat. Falmouth raised his hand to enjoin silence and the

law-breakers obeyed.

‘I have no quarrel with the Red Hundred,’ he said. ‘By the law of

this country it is permissible to hold opinions and propagate

doctrines, however objectionable they be—I am here to arrest two men

who have broken the laws of this country. Two persons who are part of

the organization known as the Four Just Men.’

All the time he was speaking his eyes searched the faces before him.

He knew that one-half of the audience could not understand him and that

the hum of talk that arose as he finished was his speech in course of

translation.

The faces he sought he could not discern. To be exact, he hoped that

his scrutiny would induce two men, of whose identity he was ignorant,

to betray themselves.

There are little events, unimportant in themselves, which

occasionally lead to tremendous issues. A skidding motor-bus that

crashed into a private car in Piccadilly had led to the discovery that

there were three vociferous foreign gentlemen imprisoned in the

overturned vehicle. It led to the further discovery that the chauffeur

had disappeared in the confusion of the collision. In the darkness,

comparing notes, the three prisoners had arrived at a conclusion—to

wit, that their abduction was a sequel to a mysterious letter each had

received, which bore the signature ‘The Four Just Men’.

So in the panic occasioned by the accident, they were sufficiently

indiscreet to curse the Four Just Men by name, and, the Four Just Men

being a sore topic with the police, they were questioned further, and

the end of it was that Superintendent Falmouth motored eastward in

great haste and was met in Middlesex Street by a reserve of police

specially summoned.

He was at the same disadvantage he had always been—the Four Just

Men were to him names only, symbols of a swift remorseless force that

struck surely and to the minute—and nothing more.

Two or three of the leaders of the Red Hundred had singled

themselves out and drew closer to the platform.

‘We are not aware,’ said Francois, the Frenchman, speaking for his

companions in faultless English, ‘we are not aware of the identity of

the men you seek, but on the understanding that they are not brethren

of our Society, and moreover’—he was at a loss for words to put the

fantastic situation—‘and moreover since they have threatened

us—threatened us,’ he repeated in bewilderment, ‘we will afford you

every assistance.’

The detective jumped at the opportunity.

‘Good!’ he said and formed a rapid plan.

The two men could not have escaped from the hall. There was a little

door near the platform, he had seen that—as the two men he sought had

seen it. Escape seemed possible through there; they had thought so,

too. But Falmouth knew that the outer door leading from the little

vestibule was guarded by two policemen. This was the sum of the

discovery made also by the two men he sought. He spoke rapidly to

Francois.

‘I want every person in the hall to be vouched for,’ he said

quickly. ‘Somebody must identify every man, and the identifier must

himself be identified.’

The arrangements were made with lightning-like rapidity. From the

platform in French, German and Yiddish, the leaders of the Red Hundred

explained the plan. Then the police formed a line, and one by one the

people came forward, and shyly, suspiciously or self-consciously,

according to their several natures, they passed the police line.

‘That is Simon Czech of Buda-Pest.’

‘Who identifies him?’

‘I.’—a dozen voices.

‘Pass.’

‘This is Michael Ranekov of Odessa.’

‘Who identifies him?’

‘I,’ said a burly man, speaking in German.

‘And you?’

There was a little titter, for Michael is the best-known man in the

Order. Some there were who, having passed the line, waited to identify

their kinsfolk and fellow-countrymen.

‘It seems much simpler than I could have imagined.’

It was the tall man with the trim beard, who spoke in a guttural

tone which was neither German nor Yiddish. He was watching with amused

interest the examination.

‘Separating the lambs from the goats with a vengeance,’ he said with

a faint smile, and his taciturn companion nodded. Then he asked—

‘Do you think any of these people will recognize you as the man who

fired?’

The tall man shook his head decisively.

‘Their eyes were on the police—and besides I am too quick a shot.

Nobody saw me unless—’

‘The Woman of Gratz?’ asked the other, without showing the slightest

concern.

‘The Woman of Gratz,’ said George Manfred.

They formed part of a struggling line that moved slowly toward the

police barrier.

‘I fear,’ said Manfred, ‘that we shall be forced to make our escape

in a perfectly obvious way—the bull-at-the-gate method is one that I

object to on principle, and it is one that I have never been obliged to

employ.’

They were speaking all the time in the language of the harsh

gutturals, and those who were in their vicinity looked at them in some

perplexity, for it is a tongue unlike any that is heard in the

Revolutionary Belt.

Closer and closer they grew to the inflexible inquisitor at the end

of the police line. Ahead of them was a young man who turned from time

to time as if seeking a friend behind. His was a face that fascinated

the shorter of the two men, ever a student of faces. It was a face of

deadly pallor, that the dark close-cropped hair and the thick black

eyebrows accentuated. Aesthetic in outline, refined in contour, it was

the face of a visionary, and in the restless, troubled eyes there lay a

hint of the fanatic. He reached the barrier and a dozen eager men

stepped forward for the honour of sponsorship. Then he passed and

Manfred stepped calmly forward.

‘Heinrich Rossenburg of Raz,’ he mentioned the name of an obscure

Transylvanian village.

‘Who identifies this man?’ asked Falmouth monotonously. Manfred held

his breath and stood ready to spring.

‘I do.’

It was the spiritue who had gone before him; the dreamer with

the face of a priest.

‘Pass.’

Manfred, calm and smiling, sauntered through the police with a

familiar nod to his saviour. Then he heard the challenge that met his

companion.

‘Rolf Woolfund,’ he heard Poiccart’s clear, untroubled voice.

‘Who identifies this man?’

Again he waited tensely.

‘I do,’ said the young man’s voice again.

Then Poiccart joined him, and they waited a little.

Out of the corner of his eye Manfred saw the man who had vouched for

him saunter toward them. He came abreast, then:

‘If you would care to meet me at Reggiori’s at King’s Cross I shall

be there in an hour,’ he said, and Manfred noticed without emotion that

this young man also spoke in Arabic.

They passed through the crowd that had gathered about the hall—for

the news of the police raid had spread like wildfire through the East

End—and gained Aldgate Station before they spoke.

‘This is a curious beginning to our enterprise,’ said Manfred. He

seemed neither pleased nor sorry. ‘I have always thought that Arabic

was the safest language in the world in which to talk secrets—one

learns wisdom with the years,’ he added philosophically.

Poiccart examined his well-manicured finger-nails as though the

problem centred there. ‘There is no precedent,’ he said, speaking to

himself.

‘And he may be an embarrassment,’ added George; then, ‘let us wait

and see what the hour brings.’

The hour brought the man who had befriended them so strangely. It

brought also a little in advance of him a fourth man who limped

slightly but greeted the two with a rueful smile. ‘Hurt?’ asked

Manfred.

‘Nothing worth speaking about,’ said the other carelessly, ‘and now

what is the meaning of your mysterious telephone message?’

Briefly Manfred sketched the events of the night, and the other

listened gravely.

‘It’s a curious situation,’ he began, when a warning glance from

Poiccart arrested him. The subject of their conversation had

arrived.

He sat down at the table, and dismissed the fluttering waiter that

hung about him.

The four sat in silence for a while and the newcomer was the first

to speak.

‘I call myself Bernard Courtlander,’ he said simply, ‘and you are

the organization known as the Four Just Men.’

They did not reply.

‘I saw you shoot,’ he went on evenly, ‘because I had been watching

you from the moment when you entered the hall, and when the police

adopted the method of identification, I resolved to risk my life and

speak for you.’

‘Meaning,’ interposed Poiccart calmly, ‘you resolved to risk—our

killing you?’

‘Exactly,’ said the young man, nodding, ‘a purely outside view would

be that such a course would be a fiendish act of ingratitude, but I

have a closer perception of principles, and I recognize that such a

sequel to my interference is perfectly logical.’ He singled out Manfred

leaning back on the red plush cushions. ‘You have so often shown that

human life is the least considerable factor in your plan, and have

given such evidence of your singleness of purpose, that I am fully

satisfied that if my life—or the life of any one of you—stood before

the fulfilment of your objects, that life would go—so!’ He snapped his

fingers. ‘Well?’ said Manfred. ‘I know of your exploits,’ the strange

young man went on, ‘as who does not?’

He took from his pocket a leather case, and from that he extracted a

newspaper cutting. Neither of the three men evinced the slightest

interest in the paper he unfolded on the white cloth. Their eyes were

on his face.

‘Here is a list of people slain—for justice’ sake,’ Courtlander

said, smoothing the creases from a cutting from the Megaphone,

‘men whom the law of the land passed by, sweaters and debauchers,

robbers of public funds, corrupters of youth—men who bought ‘justice’

as you and I buy bread.’ He folded the paper again. ‘I have prayed God

that I might one day meet you.’

‘Well?’ It was Manfred’s voice again.

‘I want to be with you, to be one of you, to share your campaign and

and—’ he hesitated, then added soberly, ‘if need be, the death that

awaits you.’

Manfred nodded slowly, then looked toward the man with the limp.

‘What do you say, Gonsalez?’ he

Comments (0)