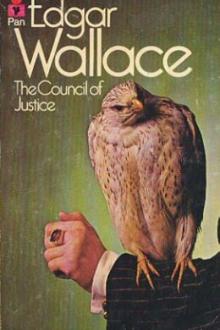

The Council of Justice, Edgar Wallace [english novels to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Council of Justice, Edgar Wallace [english novels to read .txt] 📗». Author Edgar Wallace

This Leon Gonsalez was a famous reader of faces,—that much the

young man knew,—and he turned for the test and met the other’s

appraising eyes.

‘Enthusiast, dreamer, and intellectual, of course,’ said Gonsalez

slowly; ‘there is reliability which is good, and balance which is

better—but—’

‘But—?’ asked Courtlander steadily.

‘There is passion, which is bad,’ was the verdict.

‘It is a matter of training,’ answered the other quietly. ‘My lot

has been thrown with people who think in a frenzy and act in madness;

it is the fault of all the organizations that seek to right wrong by

indiscriminate crime, whose sense are senses, who have debased

sentiment to sentimentality, and who muddle kings with kingship.’

‘You are of the Red Hundred?’ asked Manfred.

‘Yes,’ said the other, ‘because the Red Hundred carries me a little

way along the road I wish to travel.’

‘In the direction?’

‘Who knows?’ replied the other. ‘There are no straight roads, and

you cannot judge where lies your destination by the direction the first

line of path takes.’

‘I do not tell you how great a risk you take upon yourself,’ said

Manfred, ‘nor do I labour the extent of the responsibility you ask to

undertake. You are a wealthy man?’

‘Yes,’ said Courtlander, ‘as wealth goes; I have large estates in

Hungary.’

‘I do not ask that question aimlessly, yet it would make no

difference if you were poor,’ said Manfred. ‘Are you prepared to sell

your estates—Buda-Gratz I believe they are called—Highness?’

For the first time the young man smiled.

‘I did not doubt but that you knew me,’ he said; ‘as to my estates I

will sell them without hesitation.’

‘And place the money at my disposal?’

‘Yes,’ he replied, instantly. ‘Without reservation?’

‘Without reservation.’

‘And,’ said Manfred, slowly, ‘if we felt disposed to employ this

money for what might seem our own personal benefit, would you take

exception?’

‘None,’ said the young man, calmly.

‘And as a proof?’ demanded Poiccart, leaning a little forward.

‘The word of a Hap—’

‘Enough,’ said Manfred; ‘we do not want your money—yet money is the

supreme test.’ He pondered awhile before he spoke again.

‘There is the Woman of Gratz,’ he said abruptly; ‘at the worst she

must be killed.’

‘It is a pity,’ said Courtlander, a little sadly. He had answered

the final test did he but know it. A too willing compliance, an

over-eagerness to agree with the supreme sentence of the ‘Four’, any

one thing that might have betrayed the lack of that exact balance of

mind, which their word demanded, would have irretrievably condemned

him.

‘Let us drink an arrogant toast,’ said Manfred, beckoning a waiter.

The wine was opened and the glasses filled, and Manfred muttered the

toast.

‘The Four who were three, to the Fourth who died and the Fourth who

is born.’

Once upon a time there was a fourth who fell riddled with bullets in

a Bordeaux cafe, and him they pledged. In Middlesex Street, in the

almost emptied hall, Falmouth stood at bay before an army of

reporters.

‘Were they the Four Just Men, Mr. Falmouth?’

‘Did you see them?’

‘Have you any clue?’

Every second brought a fresh batch of newspaper men, taxi after taxi

came into the dingy street, and the string of vehicles lined up outside

the hall was suggestive of a fashionable gathering. The Telephone

Tragedy was still fresh in the public mind, and it needed no more than

the utterance of the magical words ‘Four Just Men’ to fan the spark of

interest to flame again. The delegates of the Red Hundred formed a

privileged throng in the little wilderness of a forecourt, and through

these the journalists circulated industriously.

Smith of the Megaphone and his youthful assistant, Maynard,

slipped through the crowd and found their taxi.

Smith shouted a direction to the driver and sank back in the seat

with a whistle of weariness.

‘Did you hear those chaps talking about police protection?’ he

asked; ‘all the blessed anarchists from all over the world—and talking

like a mothers’ meeting! To hear ‘em you would think they were the most

respectable members of society that the world had ever seen. Our

civilization is a wonderful thing,’ he added, cryptically.

‘One man,’ said Maynard, ‘asked me in very bad French if the conduct

of the Four Just Men was actionable!’

At that moment, another question was being put to Falmouth by a

leader of the Red Hundred, and Falmouth, a little ruffled in his

temper, replied with all the urbanity that he could summon.

‘You may have your meetings,’ he said with some asperity, ‘so long

as you do not utter anything calculated to bring about a breach of the

peace, you may talk sedition and anarchy till you’re blue in the face.

Your English friends will tell you how far you can go—and I might say

you can go pretty far—you can advocate the assassination of kings, so

long as you don’t specify which king; you can plot against governments

and denounce armies and grand dukes; in fact, you can do as you

please—because that’s the law.’

‘What is—a breach of the peace?’ asked his interrogator, repeating

the words with difficulty.

Another detective explained.

Francois and one Rudulph Starque escorted the Woman of Gratz to her

Bloomsbury lodgings that night, and they discussed the detective’s

answer.

This Starque was a big man, strongly built, with a fleshy face and

little pouches under his eyes. He was reputed to be well off, and to

have a way with women.

‘So it would appear,’ he said, ‘that we may say “Let the kings

be slain”, but not “Let the king be slain”; also that we

may preach the downfall of governments, but if we say “Let us go

into this cafe”—how do you call it?—“public-house, and

be rude to the proprietaire” we commit a—er—breach of

the peace—ne c’est pas?

‘It is so,’ said Francois, ‘that is the English way.’

‘It is a mad way,’ said the other.

They reached the door of the girl’s pension. She had been very quiet

during the walk, answering questions that were put to her in

monosyllables. She had ample food for thought in the events of the

night.

Francois bade her a curt good night and walked a little distance. It

had come to be regarded as Starque’s privilege to stand nearest the

girl. Now he took her slim hands in his and looked down at her. Some

one has said the East begins at Bukarest, but there is a touch of the

Eastern in every Hungarian, and there is a crudeness in their whole

attitude to womankind that shocks the more tender susceptibilities of

the Western.

‘Good night, little Maria,’ he said in a low voice. ‘Some day you

will be kinder, and you will not leave me at the door.’ She looked at

him steadfastly. ‘That will never be,’ she replied, without a

tremor.

CHAPTER III. Jessen, alias Long

The front page of every big London daily was again black with the

story of the Four Just Men.

‘What I should like,’ said the editor of the Megaphone,

wistfully, ‘is a sort of official propaganda from the Four—a sort of

inspired manifesto that we could spread into six columns.’

Charles Garret, the Megaphone’s ‘star’ reporter, with his hat

on the back of his head, and an apparently inattentive eye fixed on the

electrolier, sniffed.

The editor looked at him reflectively.

‘A smart man might get into touch with them.’

Charles said, ‘Yes,’ but without enthusiasm.

‘If it wasn’t that I knew you,’ mused the editor, ‘I should say you

were afraid.’

‘I am,’ said Charles shamelessly.

‘I don’t want to put a younger reporter on this job,’ said the

editor sadly, ‘it would look bad for you; but I’m afraid I must.’

‘Do,’ said Charles with animation, ‘do, and put me down ten

shillings toward the wreath.’

He left the office a few minutes later with the ghost of a smile at

the corners of his mouth, and one fixed determination in the deepest

and most secret recesses of his heart. It was rather like Charles that,

having by an uncompromising firmness established his right to refuse

work of a dangerous character, he should of his own will undertake the

task against which he had officially set his face. Perhaps his chief

knew him as well as he knew himself, for as Charles, with a last

defiant snort, stalked from the office, the smile that came to his lips

was reflected on the editor’s face.

Walking through the echoing corridors of Megaphone House, Charles

whistled that popular and satirical song, the chorus of which

runs—

By kind permission of the Megaphone,

By kind permission of the Megaphone. Summer comes when Spring

has gone,

And the world goes spinning on,

By permission of the Daily Megaphone.

Presently, he found himself in Fleet Street, and, standing at the

edge of the curb, he answered a taxi-driver’s expectant look with a

nod.

‘Where to, sir?’ asked the driver.

‘37 Presley Street, Walworth—round by the “Blue Bob”

and the second turning to the left.’

Crossing Waterloo Bridge it occurred to him that the taxi might

attract attention, so halfway down the Waterloo Road he gave another

order, and, dismissing the vehicle, he walked the remainder of the

way.

Charles knocked at 37 Presley Street, and after a little wait a firm

step echoed in the passage, and the door was half opened. The passage

was dark, but he could see dimly the thick-set figure of the man who

stood waiting silently.

‘Is that Mr. Long?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ said the man curtly.

Charles laughed, and the man seemed to recognize the voice and

opened the door a little wider.

‘Not Mr. Garrett?’ he asked in surprise.

‘That’s me,’ said Charles, and walked into the house.

His host stopped to fasten the door, and Charles heard the snap of

the well-oiled lock and the scraping of a chain. Then with an apology

the man pushed past him and, opening the door, ushered him into a

well-lighted room, motioned Charles to a deep-seated chair, seated

himself near a small table, turned down the page of the book from which

he had evidently been reading, and looked inquiringly at his

visitor.

‘I’ve come to consult you,’ said Charles.

A lesser man than Mr. Long might have been grossly flippant, but

this young man—he was thirty-five, but looked older—did not descend

to such a level.

‘I wanted to consult you,’ he said in reply.

His language was the language of a man who addresses an equal, but

there was something in his manner which suggested deference.

‘You spoke to me about Milton,’ he went on, ‘but I find I can’t read

him. I think it is because he is not sufficiently material.’ He paused

a little. ‘The only poetry I can read is the poetry of the Bible,

and that is because materialism and mysticism are so ingeniously

blended—’

He may have seen the shadow on the journalist’s face, but he stopped

abruptly.

‘I can talk about books another time,’ he said. Charles did not make

the conventional disclaimer, but accepted the other’s interpretation of

the urgency of his business.

‘You know everybody,’ said Charles, ‘all the queer fish in the

basket, and a proportion of them get to know you—in time.’ The other

nodded gravely.

‘When other sources of information fail,’ continued the journalist,

‘I have

Comments (0)